Final Crisis #1-7 (2008-2009)

Written by Grant MorrisonPenciled by J.G. Jones, Marco Rudy, Doug Mahnke, Carlos Pacheco

Inked by Jesus Merino, Christian Alamy and others

Colored by Alex Sinclair, Pete Pantazis, Tony Avila

Published by DC Comics

On the surface, the title of Final Crisis feels like a misnomer. How can there even be a “final” crisis? There will always be a DC Universe, there will always be earth-shattering dangers, and there will always be heroes to ensure the end is never really the end. But the strength of Final Crisis lies in that it recognizes this, and uses this fact as the crux of the entire event: the promotional tagline was, after all, “Heroes die. Legends live forever.” The characters and stories of the DC Universe are timeless, never-ending, and very much alive in the way that language can be said to be alive. It’s from this angle that writer Grant Morrison attempts to comment on and interact with DC’s complex and often unwieldy history. While Final Crisis is not the final challenge these characters will ever face (because nothing ever will be until the day DC stops publishing — and at this point that’ll likely be the same day CNN puts it “Nearer, My God, to Thee” video to use), one walks away from it feeling like they’ve just experienced the ultimate in everything the DC Universe was, is, and will be.

However, despite its lofty ambitions and elegant execution, Final Crisis does not really enjoy much prestige within the DC fan community. It may actually be neck and neck with Identity Crisis in the contest for Most Polarizing DC Crisis, though calling that winner can be tough because each has different reasons for potentially alienating its audience. Both Crises are dark, sure, but while Final Crisis offers its fair share of apocalyptic doom-and-gloom, it is, at its core, a story about superheroes doing what they do best — saving the universe — and not some Watchmen-esque exploration of the morally ambiguous underbelly of heroism like Identity Crisis. Final Crisis, however, has the distinction of having been written by Morrison, which means that to many in the audience, it’s going to come off as weird… Really, really weird.

Ever since he broke into comics, Morrison has had a reputation as being the guy who writes stories that are “weird just for the sake of being weird.” This assessment is not only inaccurate, but also really unfair. Morrison has always made it a point to explore challenging themes, try to move the medium to the next level, and take a very holistic, “everything matters/is possible” approach to his material — especially his mainstream superhero work. His stories are often sprawling and dense, he enjoys playing around with chronology and continuity, no corner of DC’s history is ever too obscure to reference, and he always makes it a point never to hold the reader’s hand. There are dozens, if not hundreds, of characters who cross the pages of the twelve issues that make up Morrison’s Final Crisis canon (which, for the curious, is Final Crisis #1-7, Superman: Beyond #1-2, Final Crisis: Submit #1, and Batman #682-683). The events of one single panel in issue #6 can call back to the events of another single panel in the Superman: Beyond tie-in. With so much exposition happening in tiny blink-and-you’ll-miss-it moments, this is a story that begs for multiple close reads to really appreciate its true weight and significance.

And what that true weight and significance is is two-fold: it’s both a rousing, bombastic superhero epic that epitomizes the best these characters have to offer, and a commentary on the readership’s relationship to the never-ending narratives of the DC Universe.

To begin, let’s tackle the former: Final Crisis tells the story of the DCU’s heroes’ final battle with manifestations of Darkseid and the other gods of Apokolips, who have made their move for domination of mankind using the dreaded Anti-Life Equation. Time is broken, humanity seems lost, heroes become villains and villains become heroes, and somewhere in the Multiverse looms a more powerful foe than even Darkseid. When it comes to this story, it really helps that it takes place in the pre-Flashpoint universe, when the DCU was a much richer, deeper place. Here, superheroes have been around for decades, and respected old-timers rub elbows and trade notes with untested newbies. Not only is there really something special about seeing Jay Garrick fighting alongside Wally West, and Alan Scott alongside John Stewart, but it also provides a lens by which we can glimpse the whole of the DC Comics legacy all at once. As such, the scope of the event is absolutely massive, and it definitely helps to enter into it with a fairly thorough familiarity with all things DC.

But it manages to pay off, as stated before, if you’re giving the story the close read it deserves. While Final Crisis does rely heavily on the readers’ familiarity with DC lore, it oddly enough also feels far more self-contained than most big comic events. It is set at a very specific point in DC history and continuity, and yet it almost feels apart from that, like as long as you know who all these character are, you don’t need to necessarily worry about where they’ve entered into this event, or what’s going on in their individual titles. This all leads to a story full of great and often surprising arcs for numerous characters from all over the DC spectrum — from the Tattooed Man to Overman to Renee Montoya’s Question to Lex Luthor to Nix Uotan, the exiled Monitor. The character moments range from humorous little gags to momentous, well-earned action beats.

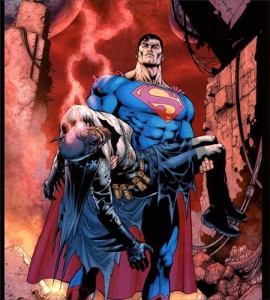

Of course, the most impressive bits are saved for the JLA, where the characters under the various banners — Batman and Superman, as well as multiple Flashes and Green Lanterns — all get to play a role in saving the day (with the problematic exception being Wonder Woman, who spends most of the story as a villain under the thrall of the Anti-Life Equation, and who doesn’t get much to do even after she is freed). Perhaps the most elegant moments belong to Batman, who, towards the end of the event, gets two issues dedicated to re-telling his entire history — not only Who He Is and How He Came To Be, but also Who He’s Become Since Then. It may sound redundant to have to relive these moments again, but the way Morrison handles it truly isn’t. By connecting various threads of Batman stories throughout the years, he forms a beautiful hypothesis about what makes Batman work as a character: Bruce Wayne isn’t Batman because of the trauma he’s experienced, he’s Batman because of his unique ability to mold that trauma into something greater. These issues of Batman aren’t collected in the Final Crisis trade, and can only be found at the back of the Batman RIP trade. This is really a shame because not only do the two issues alone not make sense when removed from the context of Final Crisis, the final confrontation between Batman and Darkseid in Final Crisis ends up losing much of its emotional potency without them.

And Morrison’s attempts to remind us of the physicality of comic books — that they are objects we hold in our hands — don’t end there. Superman and his travelling companions, a group of alternate Supermen from across the Multiverse, eventually discover the source of all creation: the Monitor, represented as a plain white page. And the Multiverse, we are told, emerges from a “flaw” within that Monitor, represented by a small dot on the white of the page, the place where a drawing may begin. The origin of creation is exactly the moment a pencil hits the page and forms into something greater.

But more than just exploring Superman and the heroes of the DC Universe physical objects, Morrison explores them as archetypes. We find that the race of Monitors — descendants from the original Monitor and Morrison’s in-story stand-ins for creators — attempted to contain the flaw by creating an eternal statue that sure looks a lot like Superman, doesn’t it? In doing this, Morrison positions “Superman” as an eternal recurring concept from which all of the DC Universe is descended (another reason the story works best in the pre-Flashpoint universe). He, like all heroes, cannot be destroyed, and he will always stand even when the darkest of humanity’s real-life experiences — which in Final Crisis take the form of the evil, vampiric Monitor Madrakk — seem to be winning. This is because he is an idea — an ideal mixture of power, freedom, compassion, wisdom, and kindness that we all hope to embody — and ideas cannot be destroyed. They may change shape, but at the core they will always be the same.

But more than just exploring Superman and the heroes of the DC Universe physical objects, Morrison explores them as archetypes. We find that the race of Monitors — descendants from the original Monitor and Morrison’s in-story stand-ins for creators — attempted to contain the flaw by creating an eternal statue that sure looks a lot like Superman, doesn’t it? In doing this, Morrison positions “Superman” as an eternal recurring concept from which all of the DC Universe is descended (another reason the story works best in the pre-Flashpoint universe). He, like all heroes, cannot be destroyed, and he will always stand even when the darkest of humanity’s real-life experiences — which in Final Crisis take the form of the evil, vampiric Monitor Madrakk — seem to be winning. This is because he is an idea — an ideal mixture of power, freedom, compassion, wisdom, and kindness that we all hope to embody — and ideas cannot be destroyed. They may change shape, but at the core they will always be the same.

This concept is beautifully realized in issue #2 of Superman: Beyond when Superman has to inscribe his own tombstone. What he puts there is sure to make every comic fan’s heart beat a little faster with excitement: “TO BE CONTINUED.” Barry Allen can come running home. Superheroes cannot die. Every end is another beginning. “You think I killed Batman?” Morrison asks with the story’s final page. “And how do you propose I, of anybody, managed to kill Batman? That’s something you cannot do.”

Final Crisis is a Master-level Class in DC Comics. It may take a couple tries to really appreciate the complexities of what Morrison is trying to do, but at the end of the day, mainstream superhero comics don’t get anymore brilliant — or beautiful — than this.