When it comes to actresses, the movie business has always had an eye for beautiful faces. Unfortunately, it has often only been an afterthought as to whether or not that beautiful face could do anything other than be beautiful. Leaf through the archives of any of the movie glamour magazines from long ago and you’ll find them a cemetery of beautiful faces primped and hyped by the Hollywood PR machine to be The Next Great Thing. Some never made it past a screen test, while others managed to survive a few screen roles, but through lack of talent, charisma, the right roles — whatever mysterious magic it is that causes a performer to click with an audience — soon disappeared, never to be heard of again. It’s a long, looong casualty list of forgotten pretties like Merrilyn Grix, Eleanor Counts, Kathy Marlowe, Myrna Dell, Sandra Giles, Jean Colleran, Sunnie O’Dea, Eve Whitney, Helen Perry, Colleen Townsend, Dawn Addams, Ina Balin, Nicole Maurey…and on and on and on.

But sometimes Hollywood gets it right.

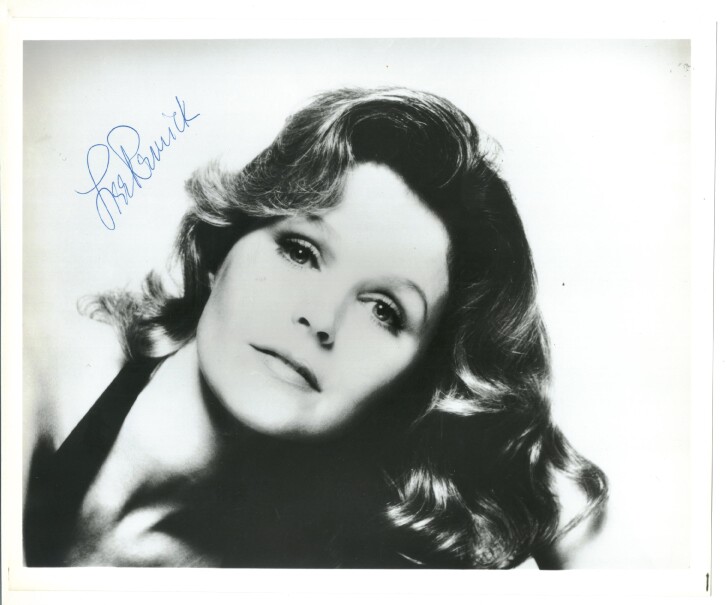

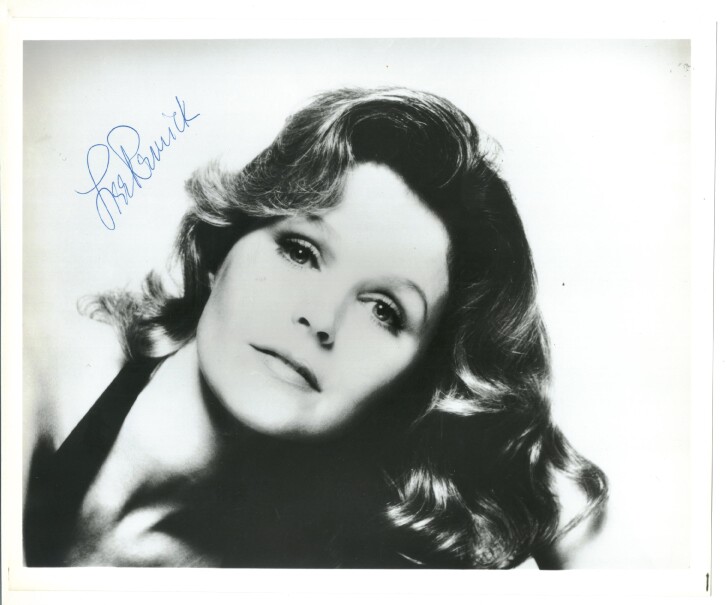

Lee Remick was beautiful. Petite, with an hourglass shape, devastating blue eyes, and the delicate features of a porcelain doll under a cascade of honey-blonde hair.

She was, in fact, beautiful to the point of distraction, considered early in her career as “America’s Answer to Brigitte Bardot.” Until she began her fight with cancer in 1989, the years remained kind to her throughout her career, allowing her an elegant, mature beauty every bit as eye-catching as the sex kitten allure of her early professional years. John J. O’Connor, reviewing the 1980 TV movie adaptation of Marilyn French’s novel, The Women’s Room, wrote of Remick that she was an “…uncommonly gifted actress whose somewhat fragile, almost stereotype good looks tend to distract one from that fact.”

“Uncommonly gifted actress.” That was the kicker. Right out of the gate, with her debut role in Elia Kazan’s prescient expose of media power, A Face in the Crowd (1957), she demonstrated a powerful, first rank talent.

She never managed to be called “great,” the way Bette Davis, or Joan Crawford, or Rita Hayworth were considered great, but then she never had that kind of iconic star aura to her either. For stars, what makes them stars is something familiar which surfaces in every role: Davis’ brassiness, Crawford’s stridency, Hayworth’s sexual heat. Remick didn’t have that; she was too good at what she did. When she finally passed in 1991, the most common word which showed up in her obituaries was “versatile.”

Born in Quincy, Massachusetts of an actress mother and a department store-owning father, she had trained for modern dance and ballet but, by her own admission, wasn’t particularly good at either. She studied acting at Barnard College and then moved on to the legendary Actors Studio, becoming part of a generation of one-of-a-kind AS alums which included Marlon Brando, Montgomery Clift, James Dean, Shelley Winters, Rod Steiger, Eva Marie Saint, Dennis Hopper, Steve McQueen, Paul Newman, Joanne Woodward… That the list doesn’t end there sends one’s head reeling, and Remick was as good at her craft as any of them.

She had been working on stage and in live TV drama when AS co-founder Kazan caught her on TV and cast her as the bimboesque baton twirler who turns the head of TV personality Lonesome Rhodes (Andy Griffith). In true AS fashion, she lived with a local family during the Arkansas shooting and practiced baton twirling so she’d come off natural on camera. And she did. When the cameras rolled, there was nothing of the well-educated young woman from Massachusetts up there, but a leggy, backwoods teen easily enthralled by a big-time TV star.

If she had a trademark that was it; that she had no trademark. The Los Angeles Times’ Charles Champlin wrote of her that in every role she “…ceased to be the actress acting and became the character.”

Her range was limitless. There was the simple, small town Texas girl of Baby, the Rain Must Fall (1965) trying to reboot a life for herself, her daughter, and husband Steve McQueen just released from prison; which was 180 degrees away from the uptown Manhattan sophisticate sexual compulsive of The Detective (1968), married to hard-bitten cop Frank Sinatra. There was her Oscar-nominated turn as the farm girl turned partying alcoholic housewife of The Days of Wine and Roses (1962), riding a wave of booze to oblivion; which was equally distant from her swivel-hipped trailer camp trash whose questionable rape puts vengeful husband Ben Gazzara (another AS grad) on trial for murder in the deliciously torrid Anatomy of a Murder (1959).

She was as adept at straight drama (Wild River, 1960, her self-professed favorite role, opposite Montgomery Clift) as broad comedy (playing a militant Prohibitionist in the comedy Western, The Hallelujah Trail, 1965). She never gave up the stage, becoming good friends with tune-meister Steven Sondheim after appearing in his short-lived Anyone Can Whistle in 1965, and copping a Tony nod two years later for Frederick Knott’s taut thriller, Wait Until Dark.

The 1960s and especially the 1970s were not generous ones for actresses, particularly those moving into their 40s. It sometimes seemed the Academy Awards had to beat the bushes to come up with 10 nominees for Best Actress/Supporting Actress categories (Example: Beatrice Straight won her Supporting Actress statue for 1976’s Network with less than six minutes of screen time; the smallest Oscar-winning performance on record). With good women’s roles dwindling, Remick smoothly transitioned back to TV continuing to turn out high caliber work racking up seven Emmy nominations in TV movies like The Women’s Room and mini-series like QB VII (1974), Jennie: Lady Randolph Churchill (1975), Ike: The War Years (1978).

When asked why she now appeared so rarely on the big screen, Remick replied, “I make movies for grownups. When Hollywood starts making them again, I’ll start acting in them again.”

My personal favorite wasn’t one of her award-nominated parts, nor the touchstone roles talked about in her obits, terrific as they all were. It was her turn in the 1968 comedy thriller, No Way to Treat a Lady, adapted from William Goldman’s novel by John Gay, and directed by Jack Smight. I remember it because it seemed to capture all of what she could do in the character of self-possessed sophisticate and wickedly sly big city survivor who, underneath all that urban savvy, was a vulnerable lonely, emotionally bruised girl.

She plays Kate Palmer, an independent, city-smart Lincoln Center tour guide – kind of an ancestral Sex and the City urban single – who may have caught a glimpse of a killer (fellow ASer Rod Steiger) who’s been strangling little old ladies. George Segal is menschy NYPD detective Morris Brummel still living at home, harangued every day by a doting mom (a hilarious Eileen Heckart) about his lack of a college diploma, wife, children, and how poorly he stacks up against his doctor brother.

From the moment she opens her door to him, Morris is smitten. She’s still half asleep, her tousled hair tumbling down unheeded into her face, and other parts of her also in danger of tumbling out of her nightgown, but she’s too damned tired to care. But, bit by bit, she awakens to the inherent decency of the cop in her doorway.

What plays out is a romance so lovingly pieced together, it’s a shame it hadn’t been lifted out of a wry serial killer thriller and dropped into a true big city romance. We see Remick – ably matched by Segal – sweet, sly, goofy, comically cunning in the way her shiksa goddess converts Momma Brummel to her side by pretending to boss her son around the same way Momma does.

But the highlight of their pas de deux takes place on Morris’ “yacht” – a police patrol boat. The relationship teeters on the brink of turning from dating to something deeper. She senses Morris’ reluctance (he’s not commitment-shy, but feels unworthy) and John Gay gives her a lovely speech: “I’ve had him already,” she tells Morris.

“Who?”

“Randy Beautiful.” She’s had the nights filled with hunks and little else, cavorted with the beautiful people who were only beautiful on the outside. In Morris, she sees the proverbial inner beauty. “Are you gentle, Morris?” she asks him, her voice a mix of hope and plaintiveness. “You can have me if you say yes.”

It’s the kind of grownup moment one rarely sees in major films these days, and even more rare is to see it done so well, with an achingly sweet honesty, and an equally sweet simplicity.

Perhaps if she had lived longer, pulled a Meryl Streep or a Glenn Close, surviving to nab the juicy mature roles that have come to both actresses, she might finally have been tagged “great” – because she was.

But whether anyone said it or not, the greatness was there, for like any great performer, she had her own voice, her own unique gifts. Said Charles Champlin, “…her beauty, both perky and patrician, and her obvious intelligence were hers alone.”

– Bill Mesce