When it comes to film interpretation and finding madness in the method, it’s only a matter of time before an overly philosophical troll decides to take an almighty stab at the man whose portfolio is stuffed with the mystery, symbolism and deeper meaning usually reserved for Michele de Nostradame and biblical verse. But while Stanley Kubrick’s horror masterpiece The Shining provided the inspiration for a film which provided the inspiration for an idea that provided the inspiration for a decidedly strange column, it is his most influential – and maddeningly metaphorical – motion picture that this week take’s it place under the warped microscope.

Since its release in 1968, 2001: A Space Odyssey has provided the creative spark for countless filmmakers and induced ever more debates trying to discern what exactly it all means. For this viewer and scribe, its point can be found in its incomprehensibility, a purpose within anarchic nonsense. A darkly minded poet of a director, Kubrick’s greatest film is a visual tome regarding the soul of humanity itself, a theme overwhelmingly prevalent in all of his much beloved work.

It seems almost like a broken record with this writer’s assertion that everything comes down to pessimistic self loathing for our species, a Freudian insistence that every small mystery can be diagnosed as the same heavy dose of misanthropy, with all symptoms pushed to support a flawed hypothesis. However, there are sufficient signs and hints within 2001 to suggest that, like the previous Strange Interpretation, Kubrick’s science fiction colossus takes a rather dim view on our species and expresses it in a medium far less linear than most auteurs truly realize. If the late great’s reclusive lifestyle doesn’t convince you that Kubrick was hardly a champion of humanity’s exponents, the tone of Full Metal Jacket and A Clockwork Orange most certainly should. Couple this with a stirring recurring theme within Odyssey’s tangent-like scenes of disconnect and you have all the hints needed to form an appropriately dark and lonely conclusion to a journey that lives up to its ironically optimistic title and still holds up as a hallucinogenic rollercoaster of wonder.

It’s a trail of breadcrumbs that begins right at the start, both of the film and of portrayed time. Every element of 2001 is celebrated, revered and immortalized by parody and tribute, so it almost becomes a tired exercise to really sit down and study just why a film dealing with aliens, treacherous AI and acid trip treasure hunting opens with a gaggle of un-evolved humans mooching around in the barren deserts of pre-civilization Africa. Yes, this is the first appearance of the decisive obelisk, a mystical extraterrestrial structure defying logic or understanding. But its sudden emergence at the home of the hominids seems timed as an unlocked new level in quickly developing game of adapting survival.

More significant are the actions of the pre-humans before the obelisk appears where an almost serene existence of feeding and lazing is replaced by needless conflict with a rival group over possession of a water hole. Before man could even speak, Kubrick is telling us, he had found reason to bear arms against his brethren when peaceful coexistence is the right route to traverse. This crucial struggle sees the early inception of territoriality, escalation and sadly, murder, as the depicted sect learn to use weapons (in this case old bones) in order to gain an advantage over their rivals. This becomes their focus, savage intelligence pre-occupied by a growing thirst and obsession with violence and destruction. When the obelisk appears, the first attempt by an unseen alien force to make contact with our species, there is not a chance that the beasts will understand the gesture. Rather, they would destroy bones with bigger bones in a display of Alpha male bravado that is half macho, half psychotic.

Cinema’s most famous match-cut follows, visually tying the film to its jump millions of years into the future as we catch up with a now space-based human race, shorn of the fur and monkey posture but, we quickly learn, not of the distrust and misled sense of supremacy. While humankind has advanced itself to levels of greatness with the advancement of technology and scientific endeavor, there exists a feeling of paranoid deception and elitism which is merely an evolved form of the unnecessary warring seen in the opening segment. William Sylvester’s character, Dr Heywood Floyd, is headed for a US moon base to investigate a stunning discovery made by scientists, one that proves the existence of extraterrestrial life. Yes, the film defining obelisk is making another appearance, deliberately buried on the lunar body four million years prior.

But instead of embracing this find and sharing it with the entire human race, the discoverers instead concoct a cover story of epidemics and withhold information from the public as they essentially look to plant their flag on the structure and keep it for themselves; so much advancement in terms of tools since the dawn of man, but still the greed and unwillingness to avoid trouble by simply sharing. This point exists in a simplistic but effective form, as Floyd opts to lie to friends and peers rather than do what ethics would compel. It is an absolutely perfect parallel, showing that intelligence has provided just a more canny thinking to help avoid unification. It comes as no surprise that upon arrival at the TMA-1, the scientists can’t think of anything more inspired to do than pose for a group photo, further cementing their arrogant claimant. The obelisk reacts by deafening them with a high pitched rattle, not so much punishment as desperate and futile attempt to communicate. A race too focused on warring and secrecy has still failed, even after so much time has passed, to understand.

This leads to the most significant episode, as a troupe of scientists are bound for Jupiter under the care of their ship’s artificial intelligence, HAL-9000. Even amongst impressive space-faring vessels capable of such long journeys, the most impressive specimen of technology is still Hal, a fully functioning and communicating computer that, while dictated by stringent programming and logical directives, still hints at possible emotion and soul thanks to being given a voice and the capacity to think. As Dave Bowman (Keir Dullea) explains in an interview with the BBC, Hal acts and sounds like a real person, but they simply do not know if there is any substance within his make up. The culture of clandestine secrecy has apparently not been shed by this point, as we quickly learn that the science team (most of whom are in suspended animation awaiting arrival at the storm planet) do not know what their ultimate destiny is, what they are supposed to do, why they are even going to Jupiter. An apparently erroneous damage report by Hal and hints at the computer’s unreliability from home base are enough to create doubt within the human occupants, and they plot to essentially overthrow Hal and disconnect him if he continues to show signs of malfunction. Unbeknownst to them, the AI has lip read every word, and is now fully aware that there is a threat to his existence.

Interpretation of what comes next in this dramatic battle comes down to your view on Hal, whether you believe that he does indeed have a soul or is just a malfunctioning machine. If it is the former to which you subscribe, you cannot help but feel sympathy for the program, as he is suddenly made aware of the fact that he could be killed at any moment, due to the fact that a report he made supposedly turned out to be false. With that line of thinking, any further action he takes could be equally misled, and result in the ultimate punishment. It becomes a matter of survival as Hal wages war on his creators, killing all but one of the science team and attempting to stop Dave, the final survivor, from ending his rampage. These actions are motivated by self-preservation, an instinct decidedly human which has apparently been transplanted into our tools of technology. The monotone with which Hal fearfully pleads with Dave to stop killing him masks the fact Hal has every right to be scared, and has essentially been betrayed and doomed to regression and decomposition.

The latter line of thinking reinforces the same message, only by different means, showing that mankind’s advancements have only come so far as to now create threats to our own existence when we ran out of natural enemies to overcome. Either way, it is a monstrous and cynical analogy posed by one of cinema’s most infamous villains, a moniker which ironically misses the point pushed on us by its presence. Regardless of your opinion on what drives Hal’s actions, it is an objective statement by Kubrick that his existence shows not the evil of technology, but the deeply flawed soul of its creator. A man’s creation will always reflect on him, and the reflection in this case is either traumatic destruction or abject failure; two roads leading to the same destination. The fact that deactivating Hal reveals to Dave the true nature of their mission is a perverse hint at a malignant, philosophical yet horribly cruel ultimate plan – the astronauts had to learn to kill life in order to discover their own purpose…apes with bones…

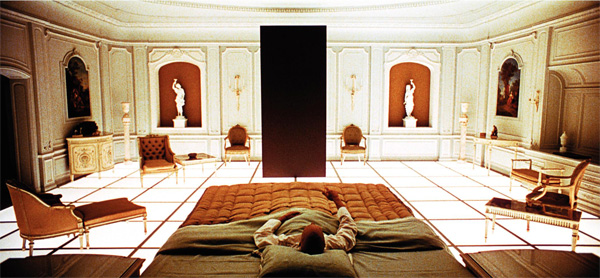

The final leg of the journey is the third and final manifestation of the obelisk, and its purpose is still unclear, even though its creators are about to take a massive leap of faith in sharing their existence with humanity. As Dave approaches the structure in Jupiter’s orbit, he is sucked into cinema’s most famous mind bending journey through the cosmos, a display of sound on sight as hypnotic as it is meaningless. Humanity’s unlikely ambassador is pulled across millions of light years into the heart of the alien beings…which looks an awful lot like a bedroom in the Louis XVI-style. Without any ability to fathom was is happening, Dave witnesses himself growing old within the room, eventually making it to his death bed as a luxurious prisoner of space and time. The obelisk appears to him, Dave reaches out and…what happens next is the crux of the film’s final message, and its interpretation falls down on either side of the optimist-pessimist debate; as odd as it may sound, a science-fiction film’s conclusion revolves around your reading of a drinking glass at 50% capacity.

One of two things occurs when David Bowman stretches a hand out to touch the obelisk and, unlike the Hal debate, whatever path you take goes to a very different place. What is a cold objective fact is that Dave is transformed into a fetus-like starchild orbiting the Earth; what this means is wholly subjective. The Mr. Brightside interpretation is that in that moment Dave finally understands what the obelisk means, what’s its appearance signifies, and his embracing of it means that mankind has displayed the intelligence to warrant the next stage of their evolution, reborn as ‘starchidren’, perhaps akin to the offspring of Krypton. After a long and perilous journey, humanity has finally reached a destination they didn’t know they were headed for or attempting to find; ascension to the next step and ultimate transcendence to a superior form of life. Woohoo to mankind. Equally, you could just view the whole sequence as a deliberately unintelligible display showing that there is no way we could possibly comprehend what comes next.

However, the finale that best fits with the previous theme of the narrative is that Dave’s rebirth is in fact a symbolic leap presented to best represent humanity’s stature; that of an undeveloped child, an unborn baby that has blundered its way into space but provides no insights, no answers and serves no purpose. Instead, it simply exists, floats in the cosmos looking at the wonders that science has created with no ability, or will it seems, to truly understand what they mean. The aliens, unseen and misunderstood, have reached out to our race and have found a species of man-children lacking in any positive traits or enlightenment. Like the viewer, Dave has no ability to comprehend what his journey has meant, what it represents, and as such humanity will continue to traipse long garden paths of mystery and spend much of the time destroying the plants rather than wondering why they are. Brooding and pessimistic, dark and weary; sound like anyone we know?

This has been a strange interpretation.

Scott Patterson