The Irish filmmaker, film historian and occasional film critic Mark Cousins has made films about films (at times to some controversy), and films about cities. I am Belfast, which he presented at the 50th Karlovy Vary, is one of the latter: dedicated to his home city of Belfast, it is a loving and somewhat experimental journey through the city and its history.

I am Belfast amazes with its physicality: it’s all about the sounds (the lilt of the language, the sounds of the streets) and the colours (the oranges and yellows of the buildings, cars, people and the blues of the sky), the way you experience a city when wandering through it mindlessly, perhaps alone to better savour all of the sensory experiences, but this time guided by someone who really knows it well. It’s about the troubled Belfast history and the mark it has left on the city as well. As he takes us on a journey through his city, some moments are stunningly powerful and the others perhaps a bit sentimental. What else could you expect from a portrait of one’s own?

In Karlovy Vary, I spoke to the director for Sound on Sight about what seem to be two of his favourite things: film, and history.

How do you think your work as a film historian and a film critic influenced your work as a director?

I’d say that if you’ve seen loads of films—which I have, I watch films all of the time—and if you can remember them, then, if you’re directing a scene, you realise that you have all these different ways of doing it. My French is very bad, and if I wanted to say something in French, I could probably only think of one word for it. If I spoke French well, I’d have five words to say it—I’d have choices. As a filmmaker, I have choices because I know how Scorsese would have done it, or Kurosawa, or whoever. I can visualise the idea, maybe use it. It helps. That is why I think filmmakers should watch loads of films.

How did you come up with this unusual concept for the film?

I come from Belfast, it’s a city that I know. When you know somewhere and you see only bits of it appearing in the media—in this case, the war aspect has been appearing in the media for twenty, thirty years now—it’s the other, the less easily defined, bits like the colour, the sound and the humour, the femaleness, the disjointedness, that you want to try and get into a film about it. Then I thought, what sort of form or style should I use? I knew that a straight observational film wouldn’t work. Nor did I want to do a fully fictional film. I thought, something hybrid. Something that captures what it feels like to walk through a city, as you said. Sometimes, when you’re walking through a city, you’re thinking very clearly about what’s in front of you, and sometimes your mind is wandering and you’re daydreaming. I think that is also how consciousness works, and great minds like Virginia Woolf have shown it—the way we tune in and out.

How does this film compare to your previous cinematic portrayals of cities—because this is your home city?

It’s quite different. My first city film was about Mexico City, where I’ve never been before. The second city film was about Tirana in Albania and I’ve never been there before either. They were honest and upfront about that I was an outsider, looking at the city for the first time. That’s a very exciting look, when you’re looking for the first time. This film was so different because not only do I speak the language, but I hear the nuances in the language, and that makes a difference. Also, because you’re not being struck by immediate visual impression—Belfast is not a particularly beautiful city, it’s definitely not Paris, but then there is a beauty in it, it is just fleeting—the sky is grey and there’s a pink wall and little moments of urban beauty that happened. I think I was able to look carefully at the city because I wasn’t seeing it for the first time, it wasn’t like a façade for me.

Speaking of media images, as a film historian, what do you think of the existing film representations of Northern Ireland?

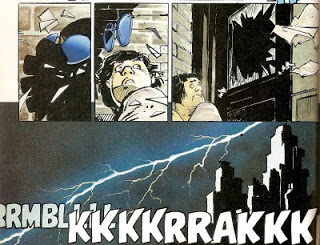

There have been very good films about Northern Ireland, Steve McQueen’s Hunger, for example. And Alan Clarke made a great film called The Elephant, which Gus van Sant remade as his Elephant. There have been good films—documentary films, fiction films. But there is a tendency to use the war as a kind of thriller. There have also been a lot of films about love across the divide, where you have a Catholic girl and a Protestant boy. That’s mostly rubbish. A lot of the films have been quite generic, focused on the war, which is the big subject. They don’t have time for subtler or poetic aspects. The place is a problem, but it’s also a place. And the place bit gets missed out.

Could the problem be that most of the representations are being made by someone other than the Irish themselves?

Yes, I think so. A lot of stuff is made in Northern Ireland, like Game of Thrones. So there is an industry, and they have established an infrastructure. But foreigners make films and their images everywhere that has been colonised—if you look at Africa, for example, films like Tarzan and the Robert Redford film Out of Africa … You need indigenous storytellers and the people from the place to tell their story. Ousmane Sembène, the great African film director, said, “we do not tell stories for revenge, but to find our place in the world.” For Northern Irish filmmakers, the films we make will help us find our place in the world. Not somebody else’s truths, but our truth. That is really important. Sembène said another thing: “A nation without cinema is like a house without mirrors.” It reflects back a certain truth. We’re still developing the film industry in Northern Ireland, but it’s getting better.

In I am Belfast, you talk about the mark The Troubles have left on the city. How present is the conflict and its consequences in everyday life nowadays?

The bloodshed is finished. We are not killing each other any more. That’s great – halle-fucking-luiah! However, the city of Belfast is still somewhat divided, Catholics are living apart from the Protestants in quite a few bits of the city, the children are still being educated separately. The problem has not gone away, it has been pushed slightly underground. Which is what happens with trauma, it gets buried and we push it down. And then, it comes out in our nightmares and our flashbacks. I’d say that we in Northern Ireland are still shocked that we could have done those things to each other. There were good reasons for it, there were social disadvantages that needed to be redressed, however, we did the most brutal things to each other that human beings can do to each other. We’re shocked and hopefully ashamed as well—I am. If there’s any kind of universal dimension to my film, then people in places like Bosnia, Congo, Mauritania will see something in that sense in my film—how could we lose our civilization? Sometimes, you need to fight for human rights, but you do not put your fellow citizens in harm’s way because of that.

There’s an excerpt from a 1919 film, J’accuse by Abel Gance, in I am Belfast, that illustrates what you’re talking about in a really powerful way that actually made me shiver.

That film, which is a masterpiece, asks something brilliant: if the dead came back, would they think that their bloodshed was valuable, was it useful? Did their fighting achieve anything? And the answer to that film is, no. These are wasted lives. In World War One, which the films refers to, there were millions of wasted lives. I wanted to ask that same question about Northern Ireland. If our dead came back, would they think that they died in vain? And I think the answer is mostly, yes. They did die in vain. You know, the struggle had to happen. It could not continue that one part of the society had all the jobs, all the houses, all the money. This social disadvantage had to change. But almost all of the killing achieved nothing, in my opinion. Some people would say that people need to die in order to get the media attention. But I would not be able to look in the eye one of those people that came back from the dead and say, it was worth it.

Would you say that a historical approach is important to you?

Yes. I think if we don’t know history, we’re only partially alive. I’d argue that in a country like Serbia, for example, or in other places, forgetting is also good. You can remember too much, or mythologise the past too much, or hang on to some flag or some battle or some injustice. So there is a danger in fetishising history, I think, in turning it into something that’s more present than the present. But overall, a kind of civilized, thoughtful, tolerant view of history is so important. It’s the sense of our heritage. Take feminism, for example. If a young woman doesn’t understand the struggle to get the vote, or to have her reproductive rights, then she might not understand why they are so important. Men, as well. We need to understand why feminism was not only one of the great struggles of its time, but one of the great philosophical movements—it thought about equality in a new way. We’re standing on the shoulders of these brave people, that’s what I’m saying.