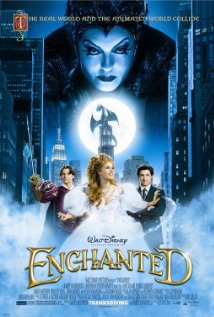

Directed by Kevin Lima

Written by Bill Kelly

Starring Amy Adams, Patrick Dempsey, Susan Sarandon, James Marsden, Timothy Spall

I have rarely seen a movie as undeserving of its lead performance as I have with Enchanted and Amy Adams. And I want to reiterate, in this column, what I said on the podcast: I think Adams’ work in this film is one of the best lead performances in any American film in a long time. It is a monumentally difficult, brave, and daring role to play. Whatever opinion people have of Enchanted is first informed by their opinion of Adams’ performance as Giselle. If she’s not so sparkling and lively and entertaining in this film, we would not be thinking of it fondly in any form. It’s not just that this is a character-driven film, it’s that it’s so singularly performance-driven, to the overall film’s detriment.

Now, it may well have gotten lost in the chatter of the episode, but I do like Enchanted on the whole. Almost all of that enjoyment is from Adams, who is frequently able to make me forget or temporarily ignore the movie’s problems. But there are some legitimately funny moments—having the male lead’s receptionist be played by the voice of Ariel from The Little Mermaid, confused and mocking Giselle’s fairy-tale mindset is clever, for example. So I don’t want to make it sound like I loathed the movie outside of Adams. I didn’t. I do think, however, that Adams is a shining star, to the point where she doesn’t lift up the other performers, dwarfing them instead. She’s not the only standout, mind you. I very much enjoy James Marsden and Timothy Spall here. All three actors are being let loose with literally cartoonish characters waking up in the real world, and while you couldn’t say any of their work is terribly subtle, each performer knows exactly how close they can get to being gratingly over-the-top and just when to avoid breaching that precipice.

The weird thing is that Enchanted plays to its strengths most when its fairy-tale characters are given literal humanity in the real world, as opposed to when those characters are in their fantasy world of Andalasia. Equally, Enchanted fails when it focuses on its real-world characters. Maybe I would’ve been warmer on the film as a whole had the real-world story not felt like such a drag. Maybe if someone who wasn’t Patrick Dempsey had been cast as the leading man, I’d like it more. (I didn’t mention it on the show, and of course, it wouldn’t have happened back in 2007, but Adam Scott from Party Down and Parks and Recreation would’ve been an excellent replacement as Robert, the strait-laced divorce lawyer.) Here’s the thing, though: everyone walks away from Enchanted crowing about Amy Adams, and rightly so. There are few films in modern history that create a movie star, few that we can point at as the beginning of an actor’s meteoric rise to fame. And while Adams wasn’t a nobody—she’d gotten a Best Supporting Actress Oscar nod for Junebug and had a memorable turn in Steven Spielberg’s Catch Me If You Can—Enchanted was a loud clarion call, a blaring neon sign pointing at Adams, demanding that we give her attention.

She deserved that attention, but because Adams, as Giselle, is so good, she’s the solar eclipse of the film, blocking out everyone else. I posed the question on Twitter before I watched the film of whether or not I’d like the movie as a whole, or just posit that, hey, Amy Adams is pretty charming, huh? One of the more common responses was: isn’t that enough? And while it’s enough to make me recommend Enchanted, it’s not enough to make me blind to the film’s flaws. Frankly, Adams’ performance is so vital to the film because otherwise, it’s just a very weak mashup of parody and tribute to the Disney Princess pantheon. Enchanted is awash in in-jokes, whether it’s through casting or visual references, far too many than I’ve noticed after having seen the film a few times in the last 5 years. But the gags are there for the truly eagle-eyed, the same people who may well work themselves ragged in the Disney theme parks looking for hidden Mickeys. (That refers to, if you’re among the uninitiated, any Mickey Mouse ears design that can be spotted in attractions, shows, attraction and show buildings, and so on, in the Disney theme parks. There are literally thousands of these Easter egg-like things.)

I think the core problem is with Patrick Dempsey, though. I fundamentally disagreed with Mike, Gabe, and our guest Kate Kulzick on the podcast about the function of the character Dempsey plays. They saw his character, the supposedly hardened and by-the-book lawyer Robert, as a way for Giselle to realize what being in the real world was like, and how that was different from her construction of reality. And while it’s necessary for Giselle to become aware of this new world she’s inhabiting, I think that Robert equally serves as either the standard-issue straight-man character, letting someone more outrageous bounce their silliness off of his terse demeanor, or as the Han Solo of the film.

I’ve never really brought it up on the show before, but the Han Solo theory—and I should probably not call it that because you’ll think it’s more highfalutin than it is—is one of many reasons, and perhaps the central reason, why the latter Matrix sequels are so terrible. (Bear with me. This will make sense soon.) The first Matrix is justly considered one of the best science-fiction films of the last 25 years, if not longer. Some of its special effects are, if not dated, not nearly as groundbreaking now as they were in 1999, but the religiously inspired story of a man who becomes a savior for humanity that’s been dominated by alien technology is thrilling, exciting, and creepy. And it’s also quite lively and funny; a great deal of that humor is thanks to the character Cypher, played by Joe Pantoliano. Pantoliano has always been an energetic character actor, full of barely hidden snide bitterness that often manifests as humor. (One of his least bitter performances, but still a funny one, comes in the excellent 1993 action film The Fugitive.)

Cypher doubts, which is what ends up being his undoing. He doubts that there’s much truth to what the wise man who runs the rebellion against the Matrix says. He doubts that much of it’s real. That doubt allows Cypher to feel like a human, whereas the other human characters in the film are so single-minded in their devotion (which, within the story, is correct, but still) that they’re like automatons. Cypher’s humanity, Cypher’s doubt, allows him to mock the world he finds so artificial. The main character of the Matrix trilogy, Neo, is meant to be the audience surrogate in the first film. He’s the guy who’s being introduced to a strange new world, but it’s Cypher who represents as much of a surrogate; Cypher might as well be looking at the audience and saying, “Can you believe this crap?” In that way, he’s like Han Solo was in the original Star Wars trilogy, at least at the beginning.

Han has as much of a character arc as Luke Skywalker does (probably more so), starting out as someone who doubts in the all-encompassing power of the Force and ending as someone who has at least allowed himself some sincerity. Han may not be the truest of the believers, but he’s bought into by the end of Return of the Jedi. He did so, though, in a human way, naturally growing as a person while still maintaining his wisecracking, sardonic nature. Cypher doesn’t make it past the first Matrix film, because the Wachowskis use him more as a Judas figure. But he’s not replaced with anyone even remotely comical or lively in the next two films. The last two Matrix movies drown themselves in self-seriousness, as the directors/writers buy too much into their own mythology, unwilling to poke any holes in it. The same lack of welcome self-deprecation occurred in the Star Wars prequels, too. (Those movies were misbegotten for many reasons, being fair.)

There needs to be a Han Solo character in Enchanted, and at first blush, the script gives us one in the form of Robert. He’s in need of loosening up and not being so cynical, and though that change can manifest by the end of the film, he’s also the perfect person to scoff at Giselle’s firmly held beliefs. Even if we know that she’s right—in that she’s not a legitimately crazy person and really does come from an animated fairy-tale world—it’s important that we see her buck up against the real world and how that completely rejects her worldview. And it’s not that there aren’t these kinds of jokes in Enchanted. It’s that, as played by Patrick Dempsey, Robert is dour, dull, and humorless. This is the guy that Giselle is going to sacrifice herself for in the third act? This is the guy she’s in love with? Certainly, Prince Edward (as played quite happily by Marsden) is a doofus who doesn’t know that he’s putting Giselle into a box she’s no longer interested in occupying. But he’s far more fun than Robert, who fits the decent-guy mold, despite being a snooze of an actor.

I realize this is subjective, as I was the only one on the podcast who dared speak ill of Dempsey’s bland performance. Maybe if I watched Grey’s Anatomy (I’ve never seen more than what appears in promo ads on ABC), I’d give him more credit or at least the benefit of the doubt. Maybe he’s better on that show than he was here. But he’s not that hot here, in a role that’s reminiscent in many ways of the one James Caan played in Elf. (By the way, we barely touched on this on the show—and when I say “we,” I mean “me”—but Enchanted is a carbon copy of Elf in many respects.) This character not only serves the function of loosening up, of becoming a more loving, caring, humane person, but of representing the counterpoint to the main character’s wackiness. And on that level, Dempsey fails. (Caan, it’s worth pointing out, isn’t a laugh riot in Elf, which is vastly superior to this movie on the whole, but his deadpan reactions to Buddy the Elf are extremely witty.)

We touched on a few more issues on the podcast, but the only one worth bringing up is one that is constantly and consistently a nitpick people have with musicals these days. Somehow, over the last 15 years or so, people have fallen under the assumption that musicals need to justify themselves, specifically in why characters will transition from speaking to singing. This is, I would argue, a very common reason why people say they don’t like musicals. And certainly, some movie musicals fail in this area, either by not making the transitions natural or by feeling embarrassed that they’re musicals. (The dream-sequence transitions in Chicago, which weren’t in the stage version, are a great example of the latter.) However, many great movie musicals work excellently, never once making you wonder why people are suddenly singing.

And I find it odd that we discussed this on the podcast in great detail, mostly because I was on the side (as was Gabe, though perhaps not as vociferously as me) in favor of movie-musical transitions. I find it strange because Enchanted, for all its flaws, is a movie that is, depending on how you look at it, either free of cynicism or at least trying to shun such a mentality. Arguably, accepting movie-musical transitions would also be an attempt to ignore cynicism, and yet I, taking the most issue with the film, was most in favor of the uncynical view.

Here’s the thing: I am sorely tempted to say that if you have a problem with the transitions from dialogue to singing in a movie musical, that’s your problem, not the movie’s problem. (To clarify: this is not an all-or-nothing scenario. As I said, some movie musicals absolutely fail at the move from one form of communication to the other for various reasons.) I brought up Singin’ In The Rain as a perfect example of an old-fashioned musical that never has to justify the transition or does a bad job of it. Mike and Kate argued that because the characters are singers and dancers, that’s why it’s not a problem. (I didn’t really get a chance to say I don’t think their profession matters, and the transitions work even when the characters aren’t making musicals but are, say, doing speech lessons. So here you go.) But really, the issue is our suspension of disbelief.

When you watch Singin’ In The Rain, or any other great musicals, such as The Sound of Music or The Music Man, the answer to the question “Why do the characters suddenly begin singing?” is: because you are watching a musical, where characters sing some of the time. Why does James Bond always sleep with a different woman in his movies, but never Miss Moneypenny, who’s very attractive and clearly interested in 007? Because you are watching a James Bond movies, where that always happens. And when you watch a Disney movie from the late 1980s or 1990s, why does a man who’s been transformed into a monster, or a boy who’s unleashed a genie from a lamp, or a lion cub, sing? Because you are watching a movie musical, where the characters sing. You have to accept that when the movie starts, or else you are already giving the movie too little credit.

I get why Enchanted wants to comment on this convention of the genre, mind you. If a person who says they’re from a fantasy world and suddenly starts singing in public—and then everyone around them also begins singing the same song in perfect tune and rhythm—you probably would be confused and throw in some asides as this strange event unfolded. It would’ve been silly for the script not to comment on the transitions. But I don’t think it’s as much a statement on how modern musicals need to justify themselves as it is an honest way of perceiving and piercing the veil of cynicism in modern culture.

Enchanted wants to be a pleasant throwback to the Disney movies we all grew up with, and it wants to turn its back on cynicism. The movie ends, as you would expect, happily, with Giselle, Robert and Robert’s daughter jumping around and dancing in their NYC apartment, ready to face the world together. (Very quickly: I was the only one on the podcast who had a big problem with Morgan, Robert’s daughter, both in conception and in execution. The others said that, because she’s in so little of the film, the girl’s bad acting is superfluous. Why, though, doesn’t the little girl have more to do? Shouldn’t we see how she reacts more to a Disney princess type walking out of animation into the real world?) I wish I could’ve shared in the same joy they felt, though I can’t blame them. Keeping Giselle in their lives is a wise move. If only for Amy Adams’ excellent work, Enchanted is a worthwhile effort from Disney. The real problem, though, is that the filmmakers were content, I think, with just coasting on her talent.