Grim Dawn released several weeks ago. I decided I was going to put it through its paces for a review, so I did what most any journalist would do: I logged into Steam, downloaded its 4-ish gigs in a handful of minutes (not even long enough for me to bother checking the time) thanks to my broadband Internet connection, and was off punching zombies before you could say, “Hey, this looks a lot like Diablo 2.”

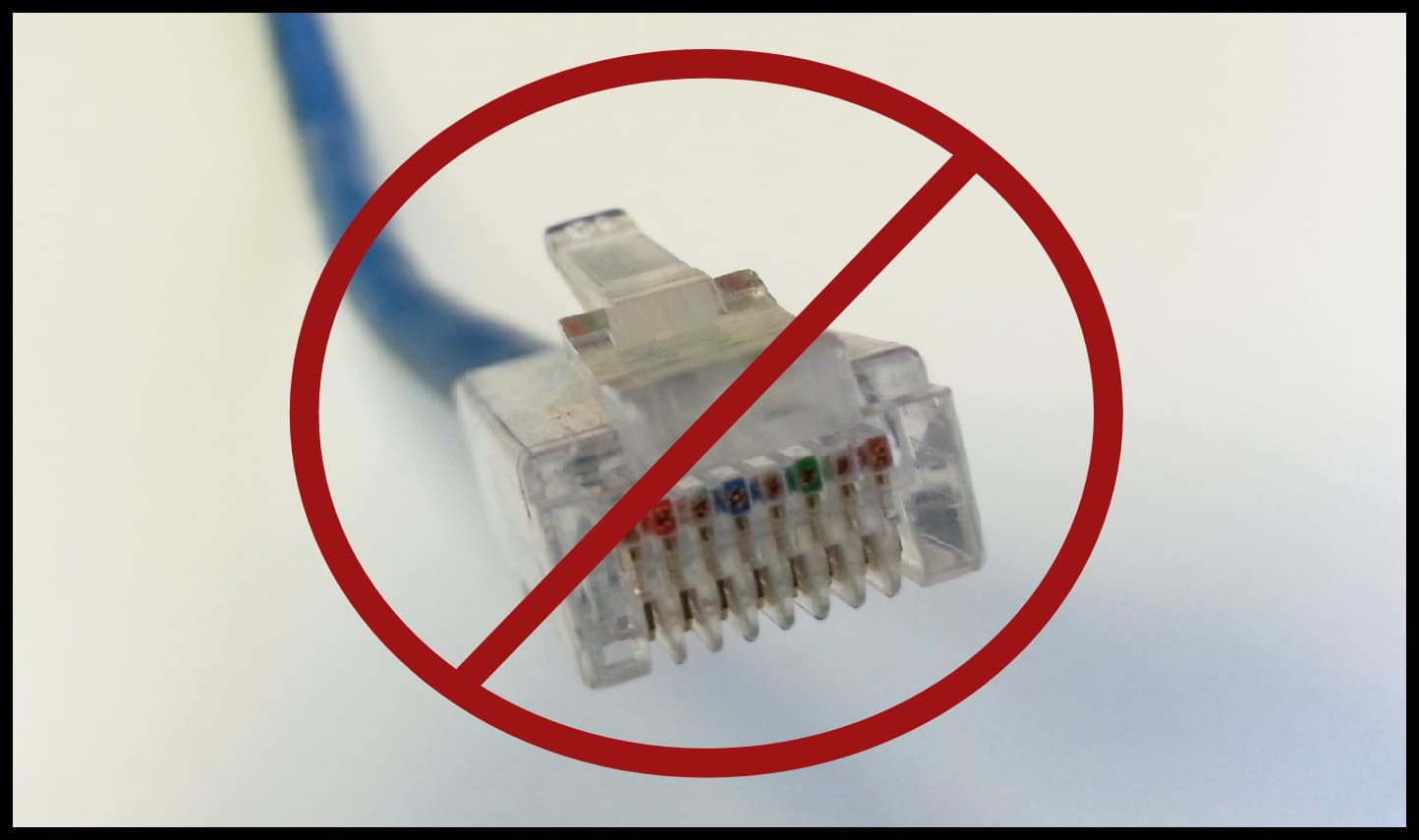

This state of things is more or less the norm for your average gamer, whether they prefer to download games via hyper-convenient services like Steam or Origin, consumer-centric sites like GOG.com, itch.io, and Humble, or the console stores of Sony, Nintendo, and Microsoft. In the era of digital distribution we certainly aren’t lacking for options, and the experiences are generally good enough that we don’t frequently feel compelled to worry about anything so mundane as transfer rates.

Sadly, not everyone has such a smooth ride, and contrary to popular belief, these people may not hail from villages tucked away on ocean-bound islands or in third world countries we can’t pronounce. A lot of them—34 million in America alone, according to the FCC’s 2016 Broadband Progress Report—are our friends and neighbors.

Jay S., a 34 year-old nuclear medicine service engineer from Illinois, is one such neighbor. As die-hard a gamer as you’re likely to find, one who has counted gaming as his main hobby for most of his life, he lives only 45 minutes outside of Chicago in a rural community, and that 45 minutes puts him at the dividing line between those who have broadband access and those who do not.

“I can see the cable lines going down Route 20,” he says. “When it crosses my road, the cable lines go down the east side because there’s a big subdivision down that way. My house is down the west side. That’s about a mile away. The phone company guy I talked to said the fiber ends on the other side of me, like a quarter mile.”

And it’s not getting better.

“No one has plans to expand it this way, because there aren’t enough people on my road to bother.”

One might well ask what happened to the promise of the Universal Service Fund, established by the FCC in 1997 to meet requirements demanded by the Telecommunications Act of the previous year. The High Cost Program of that fund, which subsidizes services specifically in remote or rural areas, is supposed to offer “support to eligible telecommunications carriers that in turn offer rates and services to consumers in rural areas,” yet despite having paid out $4.17 billion to these companies in 2013, people like Jay often still remain without access. Not that their track record had been particularly inspired in the years prior, and it makes one wonder how, according to Harvard’s Nieman Watchdog, United States consumer connections in 2006 topped out at one third the speed of South Korean and Japanese networks while costing 400% more. Given that Akamai’s State of the Internet: Q3 2015 Report doesn’t even have the US on its top-10 list for average connection speed, and that the US has long been noted in the press for paying significantly more for comparable speeds in other countries, there are far more concerns about broadband networks in the US than the scope of this article allows for.

When asked how all this makes him feel, Jay says, “You mean when I’m trying not to think about it? It’s annoying, for sure. Frustrating.”

More work in the US is still ongoing, and the FCC has since moved to transition from the USF’s High Cost Program by 2018 into what it has dubbed the Connect America Fund, which will also provide funds to wireless carriers for expanding support into rural areas. But no matter how you look at it, progress has been—and remains—slow. The FCC’s own International Broadband Data Report (Fifth), which compares European broadband statistics to those of the US, indicates that the US is currently ranked 16th of 34 countries in terms of percentage of population with overall fixed broadband subscriptions. Low-bandwidth Internet access is the hard reality for a large number of people.

Yet in the games industry, the assumption of universal broadband proliferation is rampant. Many will remember a noteworthy series of tweets between Microsoft Creative Director Adam Orth and BioWare designer Manveer Heir in 2013, prior to the launch of the Xbox One, where Orth stated that he didn’t “get the drama around having an ‘always on’ console,” and that concerned consumers should just “#dealwithit.” Even worse, when it was suggested he didn’t understand because he’d only lived in very connected places, he asked “why on earth” he would live somewhere else.

The assumption of a constant broadband connection is also prevalent in services like Steam, which don’t always offer particularly reliable offline support, and in the games-as-services movement, which has continued to grow. Even titles that don’t focus on multiplayer sometimes decide to force an online model, using features to mask what some claim is nothing more than a form of DRM or an opportunity for data mining. EA, the huge SimCity launch breakdown in 2013 notwithstanding, launched their most recent Need for Speed title as online-only (which includes the single-player content), and there was backlash against Blizzard’s Diablo III for locking the whole of its experience into the client/server model.

And perhaps worst of all, publishers have sometimes chosen to push titles out the door before they’re properly tested because they believe patching to be a reasonable practice, often resulting in both huge day-one updates and an overabundance of incremental patches that can be crushing for people with slower connections (or, perhaps even worse, data caps).

For Jay, updating has become something of an art form.

“So for PS3,” he explains, “the only way for me to play games off PSN was to use a special proxy program on my PC, connect the PS3 wirelessly to that proxy which would then connect to the Internet through my dial-up. The proxy program would capture the URL of the file the PS3 was attempting to download.” He would then go to the library to download the file using his laptop, drop the file onto his home PC and set the proxy to redirect requests for the update URL to the local file. “The PS3 didn’t care and would download it and install just fine.”

He notes that even though it couldn’t be used for piracy, as the PS3 still verified the file before he could install it, at some point that update method stopped working.

“So I haven’t bought anything off PSN in a couple years. Which really sucks now that Yakuza 5 is only on PSN. Good luck for me downloading that beast.”

For PC games, his process is often much simpler, involving a trip to the library with a netbook and a few USB sticks, but even that has its complications due to the frequency with which many games get patched.

“Steam is sort of the worst for me. Load it up and a game needs an update? Well, I’m not playing that until I get to the library to patch it. Forced patching sucks.”

While download managers tend to make getting manual updates a more manageable prospect for users on slower connections, many digital distribution services, in fact, make bad download managers. Steam will throw out any half-complete file and start over when an update times out. Jay recalls the worst of his experiences being when he tried downloading a 3 megabyte Terraria update.

“I let it run overnight,” he says. “In the morning, Steam told me it had downloaded 80 MB of data, but Terraria still wasn’t updated.”

Platforms such as GOG, Humble, and itch.io are often better options, which is why many low-bandwidth gamers have flocked to them. Because if you can’t get your games to run, all the features in the world don’t mean a whole lot.

Multiplayer is a final consideration. Most gamers without broadband have come to terms with being left out of the online multiplayer space. Dial-up subscribers have a complicated history with lag, and many of us can fondly recall the days when being an HPB (”high ping bastard”) on our favored Quake servers was something of a badge of honor. These days, the expectation of getting things up and running without a broadband connection has dropped commensurately with the increase in larger games that require more data be sent between higher numbers of people.

That said, there are still dial-up-friendly games out there, especially when it comes to turn-based strategy or card game genres, but whether or not a desired game might be one of them has become increasingly difficult to ascertain. Many titles that will, in fact, support slower connections still list broadband as a system requirement, and others that seem like they would support slower connections frequently don’t. Magic: Duels of the Planeswalkers, a 2-player card game, gave Jay headaches through lag preventing him from clicking on certain button prompts, a problem so simple it seems almost laughable; yet Hearthstone works for him without issue. Team Fortress 2 is playable, but is dependent upon whether a server sets the “minrate” command to something low enough for a low-bandwidth connection to use. Since most servers now just run the defaults, affected players are left in the cold.

It might seem as though in today’s world there would be some easy way around this problem. What about wireless Internet access? What about satellite? In Jay’s case, living in a valley with a lot of trees has made those non-options. Though he has a TV antenna on his property, it’s 10 feet too short for wireless. Getting the height for a decent signal would require new custom-built sections for the tower plus the equipment to haul it up and install it, and all that just for wireless service that at the middle tiers might manage around 3-5 Mbps down and 500k or less up. If you look to satellite or cell service, it only gets worse, as data caps are so restrictive you’d be lucky to get a single large game downloaded before exceeding your monthly limit. While there are people who have gotten really creative about dealing with their lack of Internet options, the solutions (or the funds and ingenuity to employ them) just aren’t always there.

It’s easy to think that everyone now has access to broadband, but the need for high-bandwidth connections in gaming has in many ways outstripped the infrastructure that provides them. While it may only affect a small fraction of the global market, it’s not a small number of people, and for lifelong gamers like Jay, it means the difference between what they get to play and what they simply can’t.

When asked if he had any final words to add to the discussion, he enthusiastically presented what might better demonstrate his desperation than any statistical analysis a journalist might put to paper.

“I just think the world needs to know that I beat the Diablo III campaign on PC with a dial-up connection.”

Despite the unplayable lag, his focus on strictly area-of-effect skills and imagining where the enemy might be at any given time gave him just enough edge to beat the game on the default difficulty.

“And damn it,” he says with evident pride, “that’s more hardcore than Torment X.”