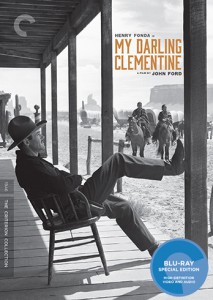

My Darling Clementine

My Darling Clementine

Directed by John Ford

Written by Samuel G. Engel and Winston Miller

USA, 1946

In John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962), it is remarked that, “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” This seems especially apt when it comes to the treatment of the Arizona city Tombstone and the historic western yarn of the gunfight at the O.K. Corral, the renowned confrontation between the Clantons on one side and the Earps with John “Doc” Holliday on the other. This famous battle, lasting all of about 30 seconds, took place the afternoon of Oct. 26, 1881, and in recalling this skirmish, multiple variations and interpretations have resulted in a cinematic legend in the making, with repeated appearances of its setting, characters, and actions. When the dust settles, one of the greatest depictions of the event, its decisive individuals, and the surrounding area and occurrences (true or false), is Ford’s own My Darling Clementine, from 1946.

The reality of this gunfight is up for debate, but Western filmmakers can’t seem to leave it alone, especially not without adding their fair share of embellishment. The facts of the incident become less interesting, certainly less exciting, than the filmic representation, and John Ford, with his take, was no exception. As John Saunders has pointed out, “Ford had more use for the already legendary figure of Wyatt Earp than the rather dubious actuality of events in 1881.” And this despite Ford’s insistence that Earp described to him exactly what happened, and that’s what we supposedly see in the film. What we do see, however, is definitely not exactly what happened.

As the Earp brothers plan to call it a day and set up camp in the southern Arizona desert, the baby faced James is left behind to tend to their herd of cattle while Wyatt (Henry Fonda) and the other brothers head into Tombstone—”wide awake, wide open” Tombstone. Ford even uses geography with a creative license here. He shoots the town as being in Monument Valley, his trademark location, which is at the opposite end of the state.

Minding their business, just passing through, and simply looking for a shave, Wyatt in particular soon finds himself in the frenzy of this reckless town. After bullets tear through the barbershop, Wyatt wonders, “What kind of town is this?” and no sooner does he utter these words than he is engaged in the seizure and removal of the guilty party, a drunken Indian. Alas, Ford was often as guilty as anyone for playing into stereotypes. Fun fact from Ford biographer Joseph McBride though: Indian Charlie is played by Charles Stevens, one of Geronimo’s grandsons.

In any case, when the brothers Earp return to their campsite, they find their cattle missing and James killed. Based on the way he handled the inebriated Native American and, even more than that, because the name Wyatt Earp carries with it considerable clout, Wyatt had been offered the position of marshal earlier in the evening and turned it down. After he discovers that the rabblerousing Clanton clan probably had something to do with James’ murder, he decides to take the job after all.

In any case, when the brothers Earp return to their campsite, they find their cattle missing and James killed. Based on the way he handled the inebriated Native American and, even more than that, because the name Wyatt Earp carries with it considerable clout, Wyatt had been offered the position of marshal earlier in the evening and turned it down. After he discovers that the rabblerousing Clanton clan probably had something to do with James’ murder, he decides to take the job after all.

Here a curious thing happens in My Darling Clementine. For a considerable portion of the film, this familial vendetta is put on hold somewhat, as Wyatt unwittingly becomes entangled in an already complex love triangle between the self-destructive Doc Holliday (Victor Mature), the less than reputable saloon girl Chihuahua (Linda Darnell), and the just-into-town Clementine Carter (Cathy Downs). To Doc (and the film), Chihuahua represents the untamed west while Clementine stands in for the civilized refinement of the east—a conflict at the heart of countless Western classics—and they’re both vying for Doc’s affection. And Wyatt, of course, inevitably develops a fancy for “Clem” as well.

Other narrative strands are incorporated into the picture, but for some time, the inaction of Wyatt stands out. Though he may not be overly concerned with the aggressive pursuit of the Clantons, Ford, as he always did so well, allows for arguably more compelling bits of supplementary business. Not the least of these is the sequence McBride calls one of the greatest scenes in American cinema and the “best scene in the film” (he’s right there). It is, he says, “pure magic.” The celebrated religious service and dance is a culmination of all things Ford: down-home music, hearty dancing, community, a folksy hero, and society taking shape in the midst of the western wilderness. When the townsfolk gather to worship and celebrate where an actual church has yet to appear, this pivotal scene typifies the times when society as a whole begins to emerge from the rustic environment. Out of this desert, a civilization will grow, standing alongside the natural landscape, in conjunction and in contrast.

My Darling Clementine, as much as it is about the story of Wyatt Earp, Doc Holiday, and the famous gunfight, also puts forth these ideas relating to an ever-evolving culture. For example, Ford arranges the town so that there is the settlement on one side of the street, consisting of bars, hotels, and other businesses, while directly across is the open desert. It’s a notable disparity emphasizing the gradual civilization being developed on one hand, while also hinting at the natural landscape being taken away on the other.

My Darling Clementine, as much as it is about the story of Wyatt Earp, Doc Holiday, and the famous gunfight, also puts forth these ideas relating to an ever-evolving culture. For example, Ford arranges the town so that there is the settlement on one side of the street, consisting of bars, hotels, and other businesses, while directly across is the open desert. It’s a notable disparity emphasizing the gradual civilization being developed on one hand, while also hinting at the natural landscape being taken away on the other.

There’s no question though, the most famous event in Tombstone’s history was the famed gunfight, which didn’t actually happen at the OK Corral but in a vacant lot on Fremont Street. Either way, of the many depictions of this famous mêlée, Ford’s is one of the best. It’s a prolonged, well staged, and intricately choreographed sequence, with several resourceful touches on the part of Wyatt and his cohorts, even if, as per the norm, it isn’t 100% accurate (old man Clanton wasn’t actually present and Doc Holliday died years later from tuberculosis).

By the end of the film, Wyatt is still reluctant to stay put. Now that he achieved his ostensible goal of revenge, the stasis of civilization doesn’t befit his nomadic temperament. He must keep moving. While he functions as one who can settle the rambunctious town of Tombstone, he isn’t content with settling himself. The town may have reached a sort of stability, but Wyatt still has some of the wild west left in him, that roaming spirit. It’s certainly not coincidental that throughout the picture Wyatt chooses as his perch a position where the wilderness is never fully out of view. He has the settlement behind him, but he is looking out toward the unsettled.

This was John Ford’s first film after his work with the Office of Strategic Services during World War II, and you get the sense that he was seeking to get back to basics in a way, to return to a black and white world where the good guys were clearly good and the bad guys were clearly bad; indeed, only Mature and Darnell convey any sense of moral duality. As McBride argues, there’s a pleasant “simplicity” about the film, even if there is some complexity underneath.

Clementine was Henry Fonda’s fourth of eight pictures made under Ford’s direction, and the film features a solid lineup of other Ford regulars as well, including Tim Holt as Virgil Earp, Ward Bond as Morgan, and Russell Simpson as the preacher, John Simpson. Jane Darwell, six years after her Oscar-winning performance in Ford’s The Grapes of Wrath, appears as Kate Nelson, and an uncredited Danny Borzage is the accordionist (he also played the instrument between shots on set as well). Even Ford’s brother Francis pops up as an old soldier lovingly referred to by Wyatt as “Dad.” New to the Ford fold is Howard Hawks stalwart Walter Brennan as Old Man Clanton. Apparently, he and Ford did not get along though and this was the first and last time these iconic Western figures ever worked together.

Clementine was Henry Fonda’s fourth of eight pictures made under Ford’s direction, and the film features a solid lineup of other Ford regulars as well, including Tim Holt as Virgil Earp, Ward Bond as Morgan, and Russell Simpson as the preacher, John Simpson. Jane Darwell, six years after her Oscar-winning performance in Ford’s The Grapes of Wrath, appears as Kate Nelson, and an uncredited Danny Borzage is the accordionist (he also played the instrument between shots on set as well). Even Ford’s brother Francis pops up as an old soldier lovingly referred to by Wyatt as “Dad.” New to the Ford fold is Howard Hawks stalwart Walter Brennan as Old Man Clanton. Apparently, he and Ford did not get along though and this was the first and last time these iconic Western figures ever worked together.

Cinematography on the film (which has never looked better than on this new Criterion Collection 4K digital restoration), was by Joseph MacDonald, something of a cinematic heavy hitter himself. Among his credits are works with Elia Kazan, Sam Fuller, and Nicholas Ray. For Clementine, he paints a notable contrast between the beauty and expanse of the open desert in the daytime and the sense of isolation and hidden danger of the town at night; in many of these nocturnal scenes, the film is as darkly lit as one of his noirs.

As would befit any John Ford film, Criterion rustled up a bountiful helping of bonus features for the new release. There’s the 103-minute prerelease version of the film, a comparison of the two versions by film preservationist Robert Gitt, the commentary by McBride, an interview with western historian Andrew C. Isenberg about the real Wyatt Earp, and a video essay by Ford scholar Tag Gallagher. There are also brief TV programs about the history of Tombstone and Monument Valley, a radio adaptation with Fonda and Downs, and an essay by David Jenkins. For film history buffs, Bandit’s Wager, a 1916 silent Western short featuring John Ford and directed by Francis, is a exceptionally pleasant addition.

Ford himself was not a fan of My Darling Clementine, though through the years, many critics have understandably held it up as one of his finest achievements. There were multiple discrepancies between the final film and the screenplay, and Fox head Darryl F. Zanuck oversaw some post-production reshoots against Ford’s will, including the controversial ending, but there are so many classic Ford touches that even these alterations seem minor by comparison. McBride quotes British critic and filmmaker Lindsay Anderson who perhaps gives the best single word description of the film: “poetic.”

And as for the historical liberties, well, as Henry Fonda said of Ford, he “used history, he wasn’t married to it.”