From the 1960s into the 1980s, one by one, the legendary studios of old – MGM, United Artists, Warner Bros.,  Paramount, Columbia, 20th Century Fox — were gobbled up by conglomerates, some of which had had almost no previous interests in the entertainment business, such as Paramount’s acquirer, Gulf + Western (a motley collection of properties ranging from Caribbean sugar companies to auto parts), and Kinney National Service (a hodgepodge of funeral homes and parking lots which bought up Warner Bros.). This corporatization of the major studios – the once mighty fiefdoms of the old moguls subjugated by invaders with little or no practical or emotional affinity for movies – is often viewed disparagingly as a sea change signaling the end of the grand Old Hollywood; the Hollywood of Gable and Garland, of Casablanca (1942)and Gone with the Wind (1939).

Paramount, Columbia, 20th Century Fox — were gobbled up by conglomerates, some of which had had almost no previous interests in the entertainment business, such as Paramount’s acquirer, Gulf + Western (a motley collection of properties ranging from Caribbean sugar companies to auto parts), and Kinney National Service (a hodgepodge of funeral homes and parking lots which bought up Warner Bros.). This corporatization of the major studios – the once mighty fiefdoms of the old moguls subjugated by invaders with little or no practical or emotional affinity for movies – is often viewed disparagingly as a sea change signaling the end of the grand Old Hollywood; the Hollywood of Gable and Garland, of Casablanca (1942)and Gone with the Wind (1939).

Factually, however, that Hollywood had been dying for years. Nearly all of the major studios were in desperate financial shape by the 1960s having been losing audience steadily since the end of World War II. In 1945, weekly attendance had stood at 80 million, but by 1950 – when there were less than 4 million US TV households to cannibalize movie-going – the weekly numbers had already plummeted to 55 million. By the mid-60s, weekly attendance had fallen below 20 million (attendance would not bottom out until 1971 at 16 million). Though swelling TV ownership would later accelerate the erosion of attendance numbers, the underlying problem was the legendary movie moguls – MGM’s Louie Mayer, Columbia’s Harry Cohn, Warner’s Jack Warner, et al — who’d been running the majors for two generations or more, were growing older and increasingly out of touch with a movie-going audience growing significantly younger.

Factually, however, that Hollywood had been dying for years. Nearly all of the major studios were in desperate financial shape by the 1960s having been losing audience steadily since the end of World War II. In 1945, weekly attendance had stood at 80 million, but by 1950 – when there were less than 4 million US TV households to cannibalize movie-going – the weekly numbers had already plummeted to 55 million. By the mid-60s, weekly attendance had fallen below 20 million (attendance would not bottom out until 1971 at 16 million). Though swelling TV ownership would later accelerate the erosion of attendance numbers, the underlying problem was the legendary movie moguls – MGM’s Louie Mayer, Columbia’s Harry Cohn, Warner’s Jack Warner, et al — who’d been running the majors for two generations or more, were growing older and increasingly out of touch with a movie-going audience growing significantly younger.

The relentlessly southbound numbers had forced the studios to sell off their back lots for their real estate value, cut  loose their vast pools of salaried talent and craftsmen, MGM had famously auctioned off the contents of its property and wardrobe departments including such treasured and iconic items as Judy Garland’s ruby shoes from The Wizard of Oz (1939), and finished one major – RKO — as a production entity. By the 1960s, most of the moguls had either been shown the door or sidelined within their own organizations. All that in mind, the studio buy-ups, in retrospect, seem less a desecration than a form of corporate Darwinism sweeping away the sclerotic remnants of Old Hollywood.

loose their vast pools of salaried talent and craftsmen, MGM had famously auctioned off the contents of its property and wardrobe departments including such treasured and iconic items as Judy Garland’s ruby shoes from The Wizard of Oz (1939), and finished one major – RKO — as a production entity. By the 1960s, most of the moguls had either been shown the door or sidelined within their own organizations. All that in mind, the studio buy-ups, in retrospect, seem less a desecration than a form of corporate Darwinism sweeping away the sclerotic remnants of Old Hollywood.

In its stead, with the new owners came a remarkable collection of production executives at nearly every one of the major movie companies. As a class, the new production chiefs were young, ambitious, as naturally inclined by their own tastes as the dire situation of their respective studios to take risks on new talents and provocative material. Most notable and representative of the breed were John Calley at Warner Bros., Paramount’s Robert Evans, and Richard Zanuck at 20th Century Fox.

Calley had been a movie producer (The Americanization of Emily [1964], The Cincinnati Kid [1965] among others) before being offered the top production job at Warner in 1969. He was a radical change from the prior generation of studio exec: laid back, informal, with an art house aesthete’s taste for movies from the likes of Akira Kurosawa, Francois Trauffaut, and Federico Fellini. Before Calley, moviemaking at the studio had been a producer-driven affair, but Calley re-directed Warner along a more auteurist path favoring directors, particularly those with a break-from-the-pack storytelling style.

Calley had been a movie producer (The Americanization of Emily [1964], The Cincinnati Kid [1965] among others) before being offered the top production job at Warner in 1969. He was a radical change from the prior generation of studio exec: laid back, informal, with an art house aesthete’s taste for movies from the likes of Akira Kurosawa, Francois Trauffaut, and Federico Fellini. Before Calley, moviemaking at the studio had been a producer-driven affair, but Calley re-directed Warner along a more auteurist path favoring directors, particularly those with a break-from-the-pack storytelling style.

Among Calley’s strengths was an ability to understand and recognize the commercial needs of the business while still providing the opportunity for creatively ambitious moviemakers to deliver a more personalized form of mainstream cinema. As an example of the former, Calley was not above pumping out a string of undistinguished, modestly-budgeted sequels to Warner’s 1971 hit Dirty Harry; a cost-efficient formula all but guaranteeing the studio a return. He also moved the studio into the post-Star Wars (1977) big-budget movie franchise game with the first – and still one of the best – comic-book inspired blockbusters, Superman: The Movie (1978).

At the same time, Calley also offered one of commercial cinema’s few true auteurs – Stanley Kubrick – an incredibly  liberal production arrangement, giving Kubrick a studio home, license to pursue whatever projects he chose at his own pace, and complete control over every aspect of his films including marketing. Kubrick’s arrangement with Warner – which extended through A Clockwork Orange (1971), Barry Lyndon (1975), The Shining (1980), Full Metal Jacket (1987), and Eyes Wide Shut (1999) – became the envy of mainstream directors everywhere.

liberal production arrangement, giving Kubrick a studio home, license to pursue whatever projects he chose at his own pace, and complete control over every aspect of his films including marketing. Kubrick’s arrangement with Warner – which extended through A Clockwork Orange (1971), Barry Lyndon (1975), The Shining (1980), Full Metal Jacket (1987), and Eyes Wide Shut (1999) – became the envy of mainstream directors everywhere.

Under Calley, Warner turned out an admirable and successful blend of the popular (The Towering Inferno [1974], Hooper [1978]), the disturbing (Deliverance [1972]), the lyrical (Jeremiah Johnson [1972], Barry Lyndon), the provocative (Dirty Harry, A Clockwork Orange), the artistically daring (Mean Streets [1973], McCabe & Mrs. Miller [1971], THX 1138 [1971]), and the prestigious (All the President’s Men [1976]). It was also under Calley that the studio saw its biggest hit up to that time with the screen adaptation of William Peter Blatty’s 1971 best-selling supernatural thriller novel, The Exorcist (1973), which turned in rentals of a then-astounding $88.5 million on a $10 million budget.

Robert Evans, who took over production at Paramount in 1966, offered a striking contrast to Calley. Flashy and self-promoting, there is little to say about Evans he hasn’t already said himself in his1994 autobiography, The Kid Stays in the Picture, as well as in the 2002 documentary of the same name.

Robert Evans, who took over production at Paramount in 1966, offered a striking contrast to Calley. Flashy and self-promoting, there is little to say about Evans he hasn’t already said himself in his1994 autobiography, The Kid Stays in the Picture, as well as in the 2002 documentary of the same name.

Evans had made his money in sportswear, his only background in the motion picture industry having been a short, unsuccessful stint as an actor in the 1950s. However, like Calley, he was passionate about movies, and showed himself to be a canny executive with an uncanny gut instinct for the box office. Evans managed to completely reverse Paramount’s faltering fortunes with a mix of the commercially popular and aesthetically impressive, among them Love Story (1970), The Odd Couple (1968), Rosemary’s Baby (1968), Romeo and Juliet (1968), Goodbye Columbus (1969), and The Godfather Parts I & II (1972 & 1974).

As the son of the legendary Darryl Zanuck, Richard Zanuck had been raised in the movie industry. When his father — who’d quit 20th Century Fox in 1956 after 23 years as the studio’s top exec — resumed charge of Fox in 1962, Zanuck the elder hired Zanuck the younger as head of production (Dick Zanuck would later be elevated to the office of company president).

Neither an art house aficionado like Calley, nor a self-promoting seat-of-the-pants exec like Evans, Zanuck was  something of a hybrid, a blend of Old and New Hollywood sensibilities. Richard Zanuck’s Fox was just as likely to turn out a piece of Old Hollywood treacle like The Sound of Music (1965) as it was a counter-culture classic like the marijuana-flavored anti-war black comedy M*A*S*H (1972), or the tongue-in-cheek convention-busting Western Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969), or high-risk gamble Planet of the Apes (1968). And, as one might expect from a production exec standing between Hollywood’s two creative poles, there were also those projects which blended the two sensibilities. If Zanuck’s Fox was going to make a grand scale period epic, then it would be in the shape of an allusion to the country’s then current embroilment in Southeast Asia in The Sand Pebbles (1966); if it was going to turn out a rather simply plotted police procedural, it would do so after injecting an unprecedented near-documentary warts-and-all authenticity into The French Connection (1971).

something of a hybrid, a blend of Old and New Hollywood sensibilities. Richard Zanuck’s Fox was just as likely to turn out a piece of Old Hollywood treacle like The Sound of Music (1965) as it was a counter-culture classic like the marijuana-flavored anti-war black comedy M*A*S*H (1972), or the tongue-in-cheek convention-busting Western Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969), or high-risk gamble Planet of the Apes (1968). And, as one might expect from a production exec standing between Hollywood’s two creative poles, there were also those projects which blended the two sensibilities. If Zanuck’s Fox was going to make a grand scale period epic, then it would be in the shape of an allusion to the country’s then current embroilment in Southeast Asia in The Sand Pebbles (1966); if it was going to turn out a rather simply plotted police procedural, it would do so after injecting an unprecedented near-documentary warts-and-all authenticity into The French Connection (1971).

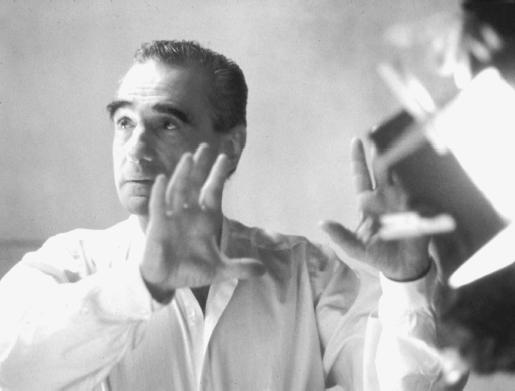

One of the salient characteristics of that generation of production chiefs was their willingness to open their respective studios to promising though relatively unproven talent. Martin Scorsese had only directed one low-budget thriller for B-movie king Roger Corman before John Calley acquired Scorsese’s independently produced Mean Streets and hired him to direct Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (1974); with the exception of his Oscar-winning screenplay for Patton (1970), Francis Ford Coppola’s box office track record as both a writer and director could only be judged underwhelming prior to Robert Evans’ tapping him to work both chores on The Godfather; TV director Franklin J. Schaffner had directed just one underperforming feature before tackling Planet of the Apes for Richard Zanuck.

One of the salient characteristics of that generation of production chiefs was their willingness to open their respective studios to promising though relatively unproven talent. Martin Scorsese had only directed one low-budget thriller for B-movie king Roger Corman before John Calley acquired Scorsese’s independently produced Mean Streets and hired him to direct Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (1974); with the exception of his Oscar-winning screenplay for Patton (1970), Francis Ford Coppola’s box office track record as both a writer and director could only be judged underwhelming prior to Robert Evans’ tapping him to work both chores on The Godfather; TV director Franklin J. Schaffner had directed just one underperforming feature before tackling Planet of the Apes for Richard Zanuck.

The flood of new talent that came into the industry under the aegis of the new studio chiefs wasn’t limited to young directorial tyros. Along with them came an equally significant collection of writers, craftsmen, and actors who helped change the substance, look, and even the sound of movies for a generation.

Among the screenwriters were Stirling Silliphant who’d served his apprenticeship as a TV writer and producer before  winning an Oscar for the screenplay of In the Heat of the Night (1967);novelist-cum-screenwriter William Goldman who won Oscars for his work on Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and All the President’s Men; and Robert Towne, another Corman graduate, who turned out such 1970s classics as Chinatown (1974) and The Last Detail (1973). There were cinematographers like Conrad Hall (Butch Cassidy), William Fraker (Bullitt, 1968)), Haskell Wexler (American Graffiti, 1973), John Alonzo (Chinatown), master of the New York milieu Owen Roizman who was nominated for an Oscar on only his second feature (The French Connection), and the legendary Gordon Willis whose work on Klute (1971), The Parallax View (1974), and The Godfather movies did for the color thriller what Nicholas Musuraca had done for black-and-white noirs a generation earlier. There were editors like William Wolf who shattered acts of violence into a hundred jarring fragments (The Wild Bunch, 1969), and Scorsese’s editorial right hand Thelma Schoonmaker (Raging Bull, 1980); and sound designer Walter Murch who turned intricately interlaced layers of distorted audio into an encrypted murder conspiracy in The Conversation (1974), and a form of musique concrete during the classic helicopter attack sequence in Francis Coppola’s Vietnam War epic, Apocalypse Now (1979).

winning an Oscar for the screenplay of In the Heat of the Night (1967);novelist-cum-screenwriter William Goldman who won Oscars for his work on Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and All the President’s Men; and Robert Towne, another Corman graduate, who turned out such 1970s classics as Chinatown (1974) and The Last Detail (1973). There were cinematographers like Conrad Hall (Butch Cassidy), William Fraker (Bullitt, 1968)), Haskell Wexler (American Graffiti, 1973), John Alonzo (Chinatown), master of the New York milieu Owen Roizman who was nominated for an Oscar on only his second feature (The French Connection), and the legendary Gordon Willis whose work on Klute (1971), The Parallax View (1974), and The Godfather movies did for the color thriller what Nicholas Musuraca had done for black-and-white noirs a generation earlier. There were editors like William Wolf who shattered acts of violence into a hundred jarring fragments (The Wild Bunch, 1969), and Scorsese’s editorial right hand Thelma Schoonmaker (Raging Bull, 1980); and sound designer Walter Murch who turned intricately interlaced layers of distorted audio into an encrypted murder conspiracy in The Conversation (1974), and a form of musique concrete during the classic helicopter attack sequence in Francis Coppola’s Vietnam War epic, Apocalypse Now (1979).

Even the music of the movies changed with the jazz flavors of Lalo Schifrin (Bullitt, Dirty Harry) and Dave Grusin (Three Days of the Condor, 1975), minimalist Michael Small (The Parallax View, Marathon Man [1976]), and the premier composer of the 1960s/1970s, Jerry Goldsmith, whose work included the all-percussion score for Seven Days in May (1964), the lush, soaring The Blue Max (1966), the haunting trumpet voluntaries of Patton (1970), and the breakthrough atonalities of Planet of the Apes.

Even the music of the movies changed with the jazz flavors of Lalo Schifrin (Bullitt, Dirty Harry) and Dave Grusin (Three Days of the Condor, 1975), minimalist Michael Small (The Parallax View, Marathon Man [1976]), and the premier composer of the 1960s/1970s, Jerry Goldsmith, whose work included the all-percussion score for Seven Days in May (1964), the lush, soaring The Blue Max (1966), the haunting trumpet voluntaries of Patton (1970), and the breakthrough atonalities of Planet of the Apes.

The performing ranks changed, too. There was still room for the square-jawed good looks of a Robert Redford and a  Paul Newman, but the new directors, in their search for a grittier, more realistic look sanctioned by the new production chiefs, opened leading roles to the kind of faces which, a generation earlier, might have been relegated to supporting character roles i.e. Robert DeNiro, Gene Hackman, Dustin Hoffman, Richard Dreyfuss, Robert Duvall, Elliott Gould, Roy Scheider, et al. The rebelliousness and discontent of the young audience was simpatico with the self-possessed, subversive spirit of an impish Jack Nicholson, or a hip, cool, anti-hero like James Coburn. There were still other actors striking a fresh, minimalist chord, their clean, low-key performances demonstrating an understanding of how little it took to fill the big screen, and which fit neatly into an evolving genre of lean, stark thrillers i.e. Charles Bronson, Clint Eastwood, Lee Marvin, and, for a time, one of the most successful of the bunch, Steve McQueen. McQueen could very well have been the poster boy for the breed, flipping through a script and judging, “Too many words, too many words. I’ll give you a close-up that’ll say a thousand words.”

Paul Newman, but the new directors, in their search for a grittier, more realistic look sanctioned by the new production chiefs, opened leading roles to the kind of faces which, a generation earlier, might have been relegated to supporting character roles i.e. Robert DeNiro, Gene Hackman, Dustin Hoffman, Richard Dreyfuss, Robert Duvall, Elliott Gould, Roy Scheider, et al. The rebelliousness and discontent of the young audience was simpatico with the self-possessed, subversive spirit of an impish Jack Nicholson, or a hip, cool, anti-hero like James Coburn. There were still other actors striking a fresh, minimalist chord, their clean, low-key performances demonstrating an understanding of how little it took to fill the big screen, and which fit neatly into an evolving genre of lean, stark thrillers i.e. Charles Bronson, Clint Eastwood, Lee Marvin, and, for a time, one of the most successful of the bunch, Steve McQueen. McQueen could very well have been the poster boy for the breed, flipping through a script and judging, “Too many words, too many words. I’ll give you a close-up that’ll say a thousand words.”

Within the welcoming – and protective — arms of the new production chiefs, this unique blend of above- and below-the-line talent was responsible for one of the most creatively daring and artistically productive periods in American commercial cinema. Look at any roster of memorable American films – the National Film Registry, the American Film Institute’s “100 Best” lists, “The A List: 100 Essential Films” compiled by the National Society of Film Critics, etc. – and one of the largest blocks, if not the largest, is typically comprised of films from the 1960s-1970s.

But streaks, by definition, end. Early triumphs earned this generation of filmmakers increasing creative license and, along with it, bigger budgets to spend on their personal visions. But, total freedom and blank checks fostered a lethal combination of hubris and indulgence, and, one after another, the wunderkind began turning out expensive flops. The execs who had brought them into the studio fold and had greenlit those pocket-draining failures were held to account.

By the late 1970s, the age of the Hollywood auteur – as well as their production chief patrons – was coming to an end.

– Bill Mesce

NEXT / PART TWO