Remakes, “re-adaptations”, and “re-imaginings” have been a frequent occurrence in cinema throughout much of its history, alongside the franchise “reboot” concept that has become particularly commonplace in the last decade. 2011, however, saw a rather curious trend of remakes of films and TV shows, either formerly original concepts or previous adaptations themselves, where the original’s story was so deeply rooted in the time period in which the film or show was initially released. Some of these seem to simply use franchise name recognition in order to cash in on nostalgia; one can’t help but question remaking Footloose, a film only remembered for its catchy soundtrack and a semblance of charm in its silly 1984 camp, with no apparent changes to the narrative outside of the type of music the kids listen to.

Regarding novels already adapted before, some filmmakers may choose to maintain the basic narrative but update the time period of the setting. This proved unsuccessful with 2011’s version of Brighton Rock, an adaptation where the 1930s setting was changed to incorporate the “mods” and “rockers” conflict of the 1960s, which faced unfavourable comparisons with both Graham Greene’s 1938 source novel and the 1947 film. A more successful approach might be to maintain the time of the previous film or series, creating a period piece instead of a time capsule. John le Carré’s 1974 novel Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy was adapted as a seven-part television series for the BBC in 1979. Rooted in the still prominent Cold War paranoia of the time, both book and series versions of the story of the hunt for a Soviet spy amongst British Intelligence stand as particularly evocative of their era. The 2011 film version keeps the story intact, but arrives with the addition of hindsight regarding the Cold War and plays with reflections on 70s Britain in a generally solid fashion. Any major problem with the 2011 film has nothing to do with it tarnishing the memory of the previous versions, but instead to do with its length not necessarily allowing the involvement one might have got from the BBC series. It’s hard to get particularly invested in the tension of the mole’s reveal when all the suspects feel like extended cameos rather than fully realised characters, but the film still has some impressive elements.

There are also remakes where filmmakers expel previous thematic content from the original in order to create something much less interesting and special. Sam Peckinpah’s 1971 thriller Straw Dogs, starring Dustin Hoffman, was a thriller with a strong anti-violence commentary running throughout, and one that dealt with a lot of ambiguity. By the majority of accounts from unimpressed critics and audiences, Rod Lurie’s new version is something more akin to a clichéd thriller where revenge is presented as righteous, and with no underlying, interesting content.

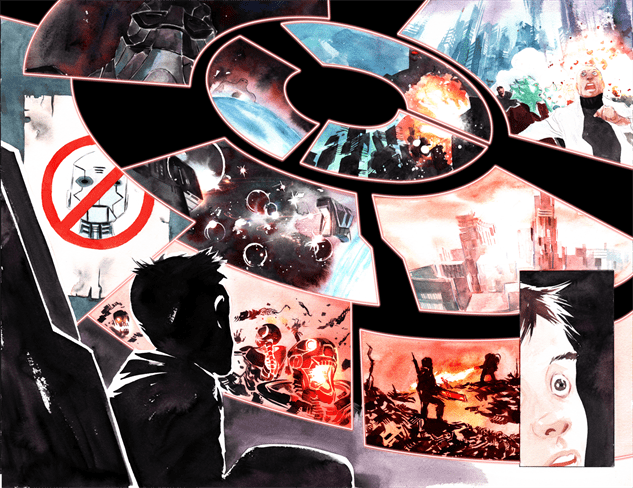

2011 brought one surprisingly good entry in the franchise reboot trend with Rise of the Planet of the Apes, which acts as both a prequel to the original 1968 film and a potential franchise starter in its own right, ignoring the continuity of the original’s sequels in the 70s. It’s also nice how this film, unlike the likes of Straw Dogs, changes thematic content from the original but in its place offers something else relevant to the era in which it is updated; while paranoia regarding nuclear annihilation fuelled the 1968 film and source novel, the more common contemporary fear of virus outbreak is a major plot point in Rise. The reboot trend also had another interesting approach earlier in the year; satirical slasher Scream 4, while lacking in some of the genuine tension and scares the first two franchise entries offered over eleven years ago, succeeds on the basis of its more comedic elements. With the film initially appearing to be an attempt to reboot the franchise with a newer, younger cast, screenwriter Kevin Williamson plays with expectations; mocking remakes and reboots in both dialogue, scene set ups and character motivations, the recurring theme is very much, to quote the film itself, “don’t fuck with the original”.

With the examples of Tinker, Apes, Scream 4, and also the recent Fright Night, the apparent successful route for remakes and reboots is to update with a fresh or new perspective, rather than just transplanting the original’s basic features in order to try to achieve a similar degree of success. The likes of the recent “premake” The Thing fail because they try to replicate what worked for others without the fresher perspective that, in general, seems to provide better results.

Josh Slater-Williams