Written by Leigh Brackett

Directed by Howard Hawks

USA, 1966

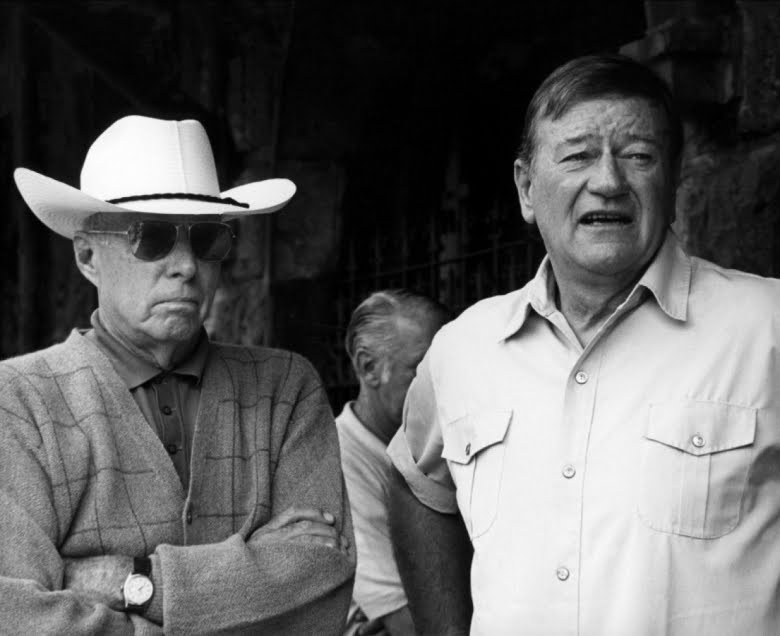

When El Dorado was first shown in 1966, the Western in its classical form was beginning to disappear from American cinema. John Ford, synonymous with the genre, released his last feature that year, and El Dorado would be the second-to-last film by its own legendary director, Howard Hawks. The Western was evolving and its old masters were giving way to modern innovators. The stylishly self-conscious films of Sergio Leone first signaled the shift (the films of his “Dollars Trilogy” came out in 1964-1966), and it was certified by the critical, ominous, and violent The Wild Bunch, directed by Sam Peckinpah in 1969. Hawks decried the slow-motion bloodletting of Peckinpah. He argued that he could kill four men, get them to the morgue, and bury them before this newcomer could get one on the ground.

With this as the context of its gestation, it’s little wonder that El Dorado feels nostalgic, like a fond farewell to a familiar style and story that once was. Hawks would still make one more Western — Rio Lobo, in 1970 — but with this film, there is a strong sense of treading well-worn territory in an effort to preserve a type of film he and his generation had created and now saw slipping away. After the failure of his Red Line 7000 the year before, Hawks was eager to get back to what he knew, even if it meant replicating an earlier success, in this case his masterful Rio Bravo. Seasoned writer and frequent collaborator Leigh Brackett did the screenplay, very loosely adapted from Harry Brown’s novel, “The Stars in Their Courses” — in fact, it’s hardly even close. Brackett also wrote Rio Bravo, but her final draft of El Dorado was, she said, the best script she had ever done. However, Hawks refashioned her script and the result, according to Brackett, derisively, was “The Son of Rio Bravo Rides Again.” Hawks would deny an outright remake, but he did unashamedly acknowledge a relative similarity: “If a director has a story that he likes and he tells it, very often he looks at the picture and says, ‘I could do that better if I did it again,’ so I’d do it again….I’m not a damn bit interested in whether somebody thinks this is a copy of it, because the copy made more money than the original, and I was very pleased with it.” Indeed, El Dorado was a fairly substantial commercial success.

Rio Bravo wasn’t the only cinematic point of reference, though. Todd McCarthy, who, with Richard Schickel and Ed Asner, provides one commentary track on the newly released Blu-ray, mentions others in his superb biography, “Howard Hawks: The Grey Fox of Hollywood.” El Dorado also alludes to prior Hawks features like Red River, A Girl in Every Port, and The Big Sleep. Hawks even worked again with the venerable cinematographer Hal Rosson, who first manned the camera for the director in 1929, on Trent’s Last Case. (Rosson’s meticulous lighting in El Dorado looks stunning on this disc.) Peter Bogdanovich, who discusses Hawks and the film on another commentary track, sums it up by calling El Dorado an “omnibus” or “anthology of things Hawks did in other pictures.”

The basic characters for El Dorado certainly bear some similarity to those in Rio Bravo. To start, there is the pairing of the sheriff, J.P. Harrah (Robert Mitchum), and his longtime friend, Cole Thornton (John Wayne). This time, the sheriff is the drunk (Dean Martin’s role in the earlier picture). There’s young gun Mississippi, played by James Caan (it was Colorado in Rio Bravo, played by Ricky Nelson). Instead of the ace sharpshooter, though, this time, the youngster can’t hit the broad side of a barn. In the beginning of El Dorado, however, there are notable differences, in terms of initial location and narrative motivation. The film is opened up more than the previous picture. For at least the first third of the film, much is shot outdoors in the desert, providing a contrast to the confines of the Old Tucson set that becomes significant later.

Plot-wise, the stage is set with a feud over water. Bart Jason (Asner) has been suspiciously expanding his landownings throughout the area. This includes into property already claimed by the MacDonald family, headed by father Kevin (R. G. Armstrong). Cole is brought in to do some work for Jason, but he’s not sure what; he just knows that he pays well. Harrah warns his friend about Jason’s violent intentions, and Cole returns the money and turns down the offer. Riding back into town, Cole is fired upon by a MacDonald son, Luke (Johnny Crawford), who had dozed off, is abruptly woken, and haphazardly shoots in his direction, assuming Cole is someone from Jason’s crew. Cole, who also expects an attack from Jason, instinctively fires back, hitting the boy in the stomach. The pain is too much for the boy to bear and he kills himself. Cole is devastated by the unintended circumstances and returns the body to the MacDonald ranch. They believe his story and he is more or less forgiven. The less being from daughter Joey (the striking Michele Carey); she shoots Cole and the bullet becomes lodged next to his spine, not an immediate concern, apparently (he is John Wayne after all), but something he should probably get checked out at some point. Cole feels guilty over the boy’s death and rides south to move on. Months later, he meets two other central characters, Nelse Macleod (played with intriguing likability by Christopher George), a top gunslinger hired by Jason for the slot Cole vacated, and Alan Bourdillon Traherne, otherwise known as Mississippi. Hearing that Harrah has become a worthless drunk and that the MacDonalds need help, Cole, with Mississippi in tow, hurries back to El Dorado, hoping to sober up the sheriff and pay penance to the MacDonalds.

Plot-wise, the stage is set with a feud over water. Bart Jason (Asner) has been suspiciously expanding his landownings throughout the area. This includes into property already claimed by the MacDonald family, headed by father Kevin (R. G. Armstrong). Cole is brought in to do some work for Jason, but he’s not sure what; he just knows that he pays well. Harrah warns his friend about Jason’s violent intentions, and Cole returns the money and turns down the offer. Riding back into town, Cole is fired upon by a MacDonald son, Luke (Johnny Crawford), who had dozed off, is abruptly woken, and haphazardly shoots in his direction, assuming Cole is someone from Jason’s crew. Cole, who also expects an attack from Jason, instinctively fires back, hitting the boy in the stomach. The pain is too much for the boy to bear and he kills himself. Cole is devastated by the unintended circumstances and returns the body to the MacDonald ranch. They believe his story and he is more or less forgiven. The less being from daughter Joey (the striking Michele Carey); she shoots Cole and the bullet becomes lodged next to his spine, not an immediate concern, apparently (he is John Wayne after all), but something he should probably get checked out at some point. Cole feels guilty over the boy’s death and rides south to move on. Months later, he meets two other central characters, Nelse Macleod (played with intriguing likability by Christopher George), a top gunslinger hired by Jason for the slot Cole vacated, and Alan Bourdillon Traherne, otherwise known as Mississippi. Hearing that Harrah has become a worthless drunk and that the MacDonalds need help, Cole, with Mississippi in tow, hurries back to El Dorado, hoping to sober up the sheriff and pay penance to the MacDonalds.

In town, and once Jason is arrested, El Dorado begins to most fully resemble Rio Bravo. There’s Wayne as essentially the same type of character, there’s the drunk, the young man, the imprisoned bad-guy boss, and an old timer, here the bugle-toting Bull, played by Arthur Hunnicutt, a less kooky variation of Walter Brennan’s Stumpy from the earlier film. Far less significant than Angie Dickinson’s Feathers in Rio Bravo, Charlene Holt is Maudie, the woman who this time courts both the Wayne and Mitchum character. With everyone settled back in El Dorado, things play out basically as before, with only minor differences, and it still remains hugely entertaining. There is exceptionally witty dialogue (“I’m looking at a tin star with a drunk pinned on it,” Cole says to the inebriated Harrah); there’s abrupt, economical, typically Hawksian action; and there’s plenty of masculine camaraderie and notions of “professional courtesy.”

El Dorado even manages to approach some of the same self-reflexive subject matter that the Peckinpah films and similar Westerns were also dealing with during this time, particularly ideas of violence and aging. Luke’s death is not only a traumatic event for those involved, but it also points to the casualness of Western brutality. So many Western characters are brazenly quick to shoot, for one reason or another, and El Dorado questions this social condition, acknowledging that frequently this violence is tragically unnecessary. Such is the level of paranoia in these Wild West days that Luke and Cole naturally assume they’re under attack and fire first and ask questions later. The lawlessness that is part and parcel in the Western is out of control, claiming innocent victims as a result of the world that has been created. Related to this and also weighing on the characters, Cole and Harrah especially, is the inevitability of old age and the fragility of the human body. Wayne more than Mitchum shows his age here (understandably, as Wayne had just undergone the removal of a cancerous lung), but by the end of the film, both characters enter the final battle as cripples; no less capable, it should be noted. Western heroes are growing more vulnerable. Their time, like the genre’s classical form, is nearing an end.

El Dorado even manages to approach some of the same self-reflexive subject matter that the Peckinpah films and similar Westerns were also dealing with during this time, particularly ideas of violence and aging. Luke’s death is not only a traumatic event for those involved, but it also points to the casualness of Western brutality. So many Western characters are brazenly quick to shoot, for one reason or another, and El Dorado questions this social condition, acknowledging that frequently this violence is tragically unnecessary. Such is the level of paranoia in these Wild West days that Luke and Cole naturally assume they’re under attack and fire first and ask questions later. The lawlessness that is part and parcel in the Western is out of control, claiming innocent victims as a result of the world that has been created. Related to this and also weighing on the characters, Cole and Harrah especially, is the inevitability of old age and the fragility of the human body. Wayne more than Mitchum shows his age here (understandably, as Wayne had just undergone the removal of a cancerous lung), but by the end of the film, both characters enter the final battle as cripples; no less capable, it should be noted. Western heroes are growing more vulnerable. Their time, like the genre’s classical form, is nearing an end.

Wayne in El Dorado is as one would expect. One brief bonus feature on the disc has former Paramount executive A.C. Lyles recalling his impressions of the Duke. Always a solid actor, he was really more of a presence. It’s truly a testament to his star status that he was able to maintain such a likable and consistent onscreen persona. Mitchum, who agreed to do the film on the basis of the most minimal of proposals (“There is no story, just you and Duke,” Hawks told him), is also in prime form, conveying a sense of effortless performance that by all accounts required considerable effort. Of the film’s main trio, Caan is the only weak note; it’s not necessarily a bad performance, just an underwhelming one. If one were to compare his version of the young-man complement to Wayne’s seasoned professional with earlier incarnations, he doesn’t have the appealing charm of Montgomery Clift in Red River or the casual coolness of Nelson in Rio Bravo.

Howard Hawks was a master at every genre he encountered, and he seemed to encounter them all. While he would only make four Westerns, they were among the very best. Against the revisionist Westerns that would soon be in vogue, or the plethora of Western television series that were on air at the time, El Dorado is a refreshing genre classic, at once suggesting topical concerns while conserving an enduring arena for its Hollywood icons to do what they do best. It incorporates much of what distinguished Howard Hawks’ cinema: his uniform themes, style, and tone. As Bogdanovich states, “If you’re a Hawks fan, it’s pretty irresistible.”

— Jeremy Carr