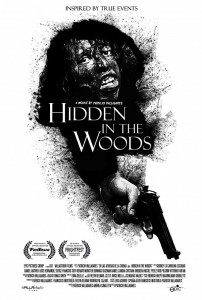

Directed by Patricio Valladares

Written by Patricio Valladares and Andrea Cavaletto

Chile, 2012

What exactly consists of a good groundhouse picture? Which conceivable, perceptible elements are sufficient for one movie fan, presumably one owing some familiarity in the genre, to conclude that groundhouse movie ‘a’ was swell, whereas movie grondhouse ‘b’ was not. Is the genre itself not supposed to give birth to films that, if assessed along the typically recognized guidelines (good acting, good story, good directing, good special effects provided said effects are present), are by and large bad? That is partly their charm, a charm virtually no other genre can claim. This year’s Fantasia International Film Festival lineup reserved some special projects for such fans. One was Michael Biehn’s directorial debut, The Victim, a film this movie reviewer found dreadful (for an altogether different take, here is Michael Ryan’s review and interview with the director himself), another being the world premier of Chilean Patrico Valladares’ Hidden in the Woods, which somehow earned far more points and more…respect, if such a quality can be ascribed to fetishistic muck like this movie. Loosely inspired by real events, by the way.

This is the sort of film for which plot matters, but only by the thinnest of margins. Plot is not of the essence. Its genuine purpose is to set the hysterics in motion, to let hell in on God’s green earth loose, unhinged, uncontrolled, unadulterated. Director Valladares’ film opens with a quick series of events from the past, relating to how sisters Ana (Siboney Lo) and Any (Carolina Escobar) got to where they are today: imprisoned in their father’s home in the Chilean countryside with little to do save being raped by dad and caring for, ill suited for the task as they may be, their younger, completely retarded brother Manuel (José Hernandez). Their father helps uncle Costello (François Soto) with the latter’s small drug empire, preserving significant amounts of products nearby for safekeeping in the event of future deals. Things take a turn for the worse, somehow, if it can be believed, on the day two police officers arrive on the premise, alerting the father to drop his chainsaw. The latter refuses, proceeds to hack the officers to bits, during which time the sisters and Manuel take off. Their major concern is that daddy was eventually apprehended, making Costello very nervous about the whereabouts of his drugs, knowledge only the girls are privy to now. It’s time to hunt them down, by any means necessary…

If that comes across as too much information divulged for a plot synopsis, readers need not worry. Despite that Hidden in the Woods barely lasts 90 minutes, there is plenty more Patricio Valladares is hiding up his sleeve, much of which would be an absolute joy to write in detail, just to convey how utterly ludicrous this film is, although that is putting the element of surprise at too great a risk for those who would want to venture down the sickly road this newcomer director invites audiences to discover. No, a sickly road he wants audiences to withstand. That seems a far more appropriate description. The difference, or one of many differences between The Victim and Hidden in the Woods is that Biehn’s film (and this is somewhat painful to write given that, as an actor, Biehn is consistently a delight) seems to believe that it is funny, ‘believe’ being the key word in the sentence. By believing that it is funny, it attempts to play a dangerous game, one that the ‘bad’ grindhouse films also engage in. It plays things in a way that tries to keep a straight face but knowing it’s all actually kind of funny, the main problem being that it isn’t. Woods does not aim for such a treacherous target. If any audience members laugh (as I did, I will confess) it is because of the lunacy of the on screen events and character beats. They are not played in that cheeky way where the cast and crew is pretending to put on a straight face but laughing to themselves deep inside. Valladares’ picture is truly off the wall, out of this world. In some ways, the film is so ostentatious in its display of depravity, it feels inhuman

What does one write about concerning performances in a movie such as this? The actresses portraying the sisters are essentially moaning in fear or yelling hyper-actively throughout the entire picture. But would they not? It seems as though every single character with a penis in this movie, with the exception of their literally simple-minded brother, wants to violate them before proceeding with other, more immediately physically painful torture methods in order to extract the secretive intelligence of the highly coveted drugs. The only actor who displays any semblance of class is François Soto, who plays the uncle, for he is the one who has attained any level of socio-economic sophistication, what with his beautiful house, his millions of dollars, his attractive attire. Soto is the sole actor giving anything resembling what is traditionally considered to be a performance.

All of this prattling makes it sounds as though the film is an atrocious mess. It is, on countless levels, but a good one, a fun one. Take for examples the fact that other than François Soto, no one is behaving normally in the film. That makes sense, given that not one individual from this family has the faintest notion of what consists of normalcy to begin with. The father? He is but a low level, brutish drug dealer who enjoys having sex with his own daughters. Ana and Any? They are the victims of said rape crimes and have enjoyed little to no contact with the outside world for the majority of their lives, secluded by the iron fist of their father. Manuel? Well, no need to dwell too much on that character. It may read as though the review is stretching for excuses to praise the film, but at least on a minimal level, the ‘characters’ are set up in the opening few scenes. There is not one action they perform that should cause the audience to cry foul with ‘Hey, that makes no sense!’ The people in this film perform excruciatingly stupid and vile acts, but none will seem out of character, which, funnily enough, is one of the movie’s strength. Consistency. That and the commendable point that everyone is extremely committed to their roles, playing everything as straight as possible

The real star of the show is not in front of the camera but rather behind it. Director Patricio Valladares directs the hell out of this twisted little pet project of his. It is in this particular department that the picture finds its true energy. A flat, colourless, ‘realistic’ depiction of the nearly unbelievable scenes which transpire here would have resulted in the death of the movie. Instead, Valladares pumps the scenes with admirable energy. The cinematography, editing and camera angles are very raw, gritty and zip along at a breakneck pave most of the time. One can almost imagine that, as fatigued as some of the actors must have been after takes during which they ran, ducked jumped and yelled incessantly, Patricio Valladares was trying to catch his breath right along with them. For a movie with so much death and vulgarity, it is the director who makes it all palatable. Well, sort of palatable. For a small number of people (nearly three-quarters of the audience got up immediately after the film, feeling absolutely no obligation whatsoever to remain for the Q&A session). Astute readers get the point.

Does the nature of the subject matter validate the undeniable energy infused by the director? Conversely, does Valladares’ impressive gusto perhaps validate the subject matter of his picture? Oh, dear, the queries this movie encourages one to ask oneself. At this stage of the festival, I have seen 34 films and not one has reached the heights where they combined a) the unabashed depiction of hysteric vulgarity and b) actually earning it. The movie is fun, albeit a type of amusement fit for a finite number of movie goers.

-Edgar Chaput