They say timing is everything, and somehow, I managed to have good timing with some of the clothes I chose to wear to Fantastic Fest in Austin, Texas. (Bear with me and my nerdiness.) I had picked out an Epcot-specific T-shirt to wear to Day Two of Fantastic Fest, in some goofy way to tie into Escape from Tomorrow, which screened that morning. Of course, then I thought I wouldn’t be attending said screening; the machinations that went into place to secure me a spot, as mentioned in that Day Two report happened so immediately that I realized I was no longer ironically dressed for the occasion in Disney gear. But as it happens, I wore that shirt, with the design of The American Adventure, the centerpiece of Epcot’s World Showcase, to Day Four of the festival. And, as luck would have it, a shirt commemorating one aspect of a globally conscious theme park befit the day aptly. My fourth day at the festival was also the fullest, as I saw six—yes, really, six—movies, from dawn until well past dusk.

They say timing is everything, and somehow, I managed to have good timing with some of the clothes I chose to wear to Fantastic Fest in Austin, Texas. (Bear with me and my nerdiness.) I had picked out an Epcot-specific T-shirt to wear to Day Two of Fantastic Fest, in some goofy way to tie into Escape from Tomorrow, which screened that morning. Of course, then I thought I wouldn’t be attending said screening; the machinations that went into place to secure me a spot, as mentioned in that Day Two report happened so immediately that I realized I was no longer ironically dressed for the occasion in Disney gear. But as it happens, I wore that shirt, with the design of The American Adventure, the centerpiece of Epcot’s World Showcase, to Day Four of the festival. And, as luck would have it, a shirt commemorating one aspect of a globally conscious theme park befit the day aptly. My fourth day at the festival was also the fullest, as I saw six—yes, really, six—movies, from dawn until well past dusk.

My day began with a press screening of the new American revenge thriller Blue Ruin. Another great thing about film festivals is the number of films playing that feel like adaptations of short stories, a trend that feels like it’s happening less and less in Hollywood these days. Blue Ruin is one such movie, a well-paced genre piece that calmly, patiently unfolds its story by saying as little as possible while letting the visuals do the heavy lifting. It calls to mind nothing short of a modern-day take on Flannery O’Connor’s best work. Dwight (Macon Blair) is a long-haired, bearded drifter on the East Coast who is informed by a friendly cop one day that the man who brutally killed his parents 20 years ago is finally being released from prison. Despite not having much of a deeply considered or airtight plan, Dwight decides to have his revenge on the man as well as his odious hillbilly family, all of whom seem to be profiting far more than he or his anguished sister ever did.

Writer/director/

The carousel of world cinema continued for me Sunday morning with a wade into the pool of animation. And yes, Fantastic Fest does offer animation (mostly shorts) throughout its eight days, though it can be more challenging to find animated features that fit the festival’s MO. O’Apostolo, the feature in question, is something dark and adult without feeling like it forces itself to be either. Mostly, O’Apostolo is adult less because of gruesome or heavily R-rated content, and more because it’s hard to imagine kids clamoring to see a Gothic fable about an escaped prisoner stuck in a spooky little town in search of stolen jewels. Writer-director Fernando Cortizo has, if nothing else, opened up a grim and fascinating little world of impressive, old-fashioned mythology. And because O’Apostolo is a stop-motion-animated film, it’s got a delightfully homemade look and feel.

The character design in the film is striking and pleasing, as if the animators found a group of wooden figurines and brought them to life. The stumbling block, then, isn’t the quaint look, but the story taking too long to unravel over just under 90 minutes. Ramon, the fugitive protagnist, is in far less danger of being caught by the authorities than he is by the mysterious forces at play in the small town of Xanaz, where the aforementioned jewels are supposedly stashed. The town elders Ramon comes in conflict with are plenty portentous, but their darker plan is revealed just in time for the climax, making the first two acts pleasant and compelling, but somewhat adrift and lacking a pure driving force. Still, O’Apostolo is the kind of movie I’m glad to see get made, even with minimal name recognition to most folks in the States. (Philip Glass contributed to the score, and Geraldine Chaplin provides one of the voices of the townsfolk.) Animation is a medium, not a genre. O’Apostolo, story slackness aside, helps prove that point. (A quick note: I realize that subtitles have typos sometimes, but if you played a drinking game by chugging each time you see a typo in this movie, you’d be dead in 20 minutes.)

Things took a turn for the strange with my third film of the day: the latest from Michel Gondry, called Mood Indigo. (I know, I know, contain your shock. A Michel Gondry film is weird.) It doesn’t yet have US distribution, so who knows when every Stateside Gondry superfan will get a chance to check it out. And Gondry tends to be a hit-or-miss director; for every Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, there’s The Green Hornet. Mood Indigo lands closer to the former, thankfully, though doesn’t quite have the same emotional power. What starts out as an uber-quirky romance between Colin (Romain Duris) and Chloe (Audrey Tautou) turns into a fairly downbeat meditation on the death of whimsy in modern society.

So, being fair, if you’re not into whimsy, you may not survive the first hour of Mood Indigo, which honestly made me wonder if any other film in history could match its deliberately quirky and odd sensibility. Gondry, who co-wrote the film with producer Luc Bossi, injects enough goofy humor as Colin and Chloe dance, skate, run, and hop through their star-crossed romance, in a world that seems untethered to the real world. The emotional turn in the third act, precipitated by Chloe falling ill due to an errant water lily in her lung, mostly works even though the final few minutes are terribly abrupt. Mood Indigo is a sweet film filled with longing and a swooning mentality; however, it doesn’t come as a surprise that the original cut was just over 2 hours, while the cut at Fantastic Fest was just over 90 minutes. Mood Indigo may not have been as memorable as a longer piece, but it might have felt fuller and more complete. Its darkness notwithstanding, this film’s a visual treat, and possibly the most uninhibited from normalcy Michel Gondry’s ever been.

The screwy and twisty continued to win the day with my next screening: Ari Folman’s The Congress. Based on a novel by Stanislaw Lem of the similarly heady Solaris, The Congress starts with a fairly satiric concept and then spirals far out of control well before even its first hour is complete. Robin Wright plays herself, or a slightly skewed version of herself. She’s a devoted mom, especially to her son (Kodi Smit-McPhee), who’s quickly becoming dead and may soon be blind. Her career has mostly fizzled, thanks in no small part to her “lousy choices,” also known as trepidation about various roles or costars. Despite her unwavering principles and stubbornness, she chooses to sign a final contract with Miramount Studios (Get it? Get it?). In effect, she signs herself away so the studio can make whatever movies they want with a computerized version of her that will never age, talk back, back off, and more. This choice has…let’s say unexpected ramifications later in her life.

The less I say about where The Congress goes, the better, but once that time-jump occurs, the tone shifts wildly and Folman, director of the Israeli film Waltz with Bashir, indulges in a change of medium, from live-action to animation. Though Wright looks essentially the same–and so do the many other human likenesses in this hallucinatory world, just a slightly twisted type of rotoscoping, almost–the environment she inhabits is meant to be psychedelic and phantasmagorical. I’d be lying if I said it didn’t work some of the time, but the film spins in and out of control so rapidly, it’s almost painful. The first third is so assured and confident, even if a bit of the inside-baseball humor is somewhat obvious. The rest is extremely bold and daring, but the two parts never totally cohere. Wright is excellent in live and animated forms, and the rest of the ensemble, especially Harvey Keitel as Wright’s agent, back her up capably. The story’s internal logic, or lack thereof, only serves to make The Congress sometimes seem like a disaster, and sometimes like an ultra-ambitious sci-fi epic, a would-be 2001: A Space Odyssey for the modern age. This movie bites off way more than it can chew; though Ari Folman didn’t quite stick the landing, I’m impressed at the attempt.

As the sun set–not on the day as a whole, mind you–I sat down to watch a homespun tale of teenage betrayal, theft, and romance. And I do mean “homespun,” though “homemade” is perhaps a more appropriate descriptor. We Gotta Get Out of This Place, you see, was made in Texas, with a few folks in the blogging community helping the film’s production in some way. This familiarity aside, We Gotta Get Out of This Place is a mostly solid and tense drama with more than a hint of noir.

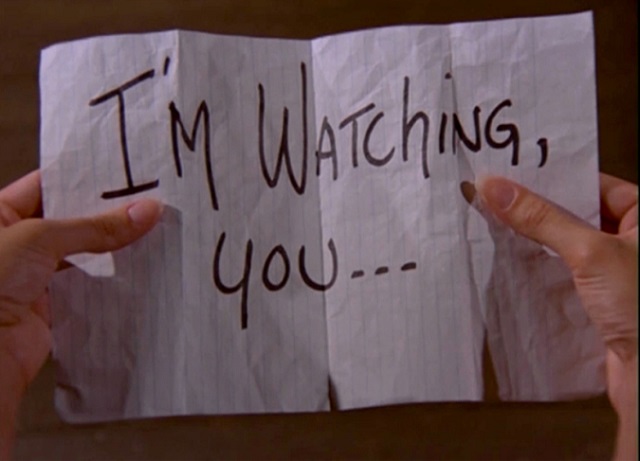

There’s three teenagers idling their days away in the small town in which the majority of the film is set: Bobby, BJ, and Sue. Bobby and Sue are weeks away from heading off to college, to the chagrin of BJ, her boyfriend. He chooses, in the pre-credits scene, to rob from his boss’s safe, but said sleazebag (Mark Pellegrino of Lost and Supernatural) doesn’t take long to figure out, kind of, who’s responsible. He soon coerces the teenage trio to rob a bigger take from his even more feared and vicious boss. As Sue says early, quoting the author Jim Thompson, “Things are not what they seem.” She’s all too correct, and as the story unfolds, directors Zeke and Simon Hawkins allow the teens’ various foolish actions to play out without rushing the story’s tangles and snarls. Though a few of the choices the characters make, specifically Bobby, feel more like script conveniences than natural decisions, the leads are so captivating and realistic in their work that it’s only ever slightly annoying. Pellegrino has the showiest role, as Giff, and digs right in. No doubt, he’s very hammy, but it’s the kind of over-the-top that’s immensely fun to watch. And though it’s a bit nasty and grim, so too is We Gotta Get Out of This Place. The Hawkins brothers, like Blue Ruin‘s Jeremy Saulnier, are talents to watch. Hopefully, they’ll get more feature opportunities in the years to come.

My final film of Day Four of Fantastic Fest, the finale of this world showcase, was another crime drama, an intense psychological thriller that takes a few cues from Joel and Ethan Coen, among other auteurs. It’s the Israeli film Big Bad Wolves, from writers-directors Aharon Keshales and Navot Papushado. Their first film, unseen by me, was a horror film called Rabies; this film operates in mental and visceral fear more than anything fantastical. A young girl goes missing after a game of hide-and-seek in the woods, and is soon found elsewhere in the forest with her head chopped off and placed in parts unknown. The cop heading the case, Miki (Lior Ashkenazi), is blamed for the girl dying thanks to a viral video of him and a few other dirty cops beating senseless a meek schoolteacher who Miki presumes is the prime suspect. Gidi, the grieving father, believes the same and chooses to abduct the teacher to torture the truth out of him, with Miki’s reluctant help.

Yes, it’s another real charmer, isn’t it? Bleakness aside (and oh my, is this bleak), Big Bad Wolves is another assured and confidently crafted thriller, out of the many I’ve seen so far over the last few days. Keshales and Papushado have a twisted sense of humor, as well, as gallows humor makes more than a few appearances, or simply off-the-wall black comedy. A good example is early on, when Miki is chewed out by his commanding officer…and his commanding officer’s son, on Take Your Child To Work Day. Or when Miki, looking for help, comes across a man from a neighboring “Arab village,” and the villager pointedly asks Miki why all Israelis presume everyone wants to kill them. There’s a sly bit of social commentary going on here, in that the only decent character we meet in the final two-thirds of Big Bad Wolves is an outsider. Those on the inside have had their souls eaten away by paranoia, violence, and more. Eventually, the bleakness becomes so oppressive that the humorous moments from earlier stand in such stark opposition that I consider them now a bit off-key. (And the less said about the often outrageously bombastic score, the better.) But Keshales and Papushado have the skills to be grim craftsmen of dark crime sagas, if Big Bad Wolves is any indication. The mental violence is as painful to watch as the physical.

Next up for me: my last day at Fantastic Fest. I’m heading home tomorrow, back to Phoenix, my wife, and my cats. (And my job. And…well, you get the picture.) But today, I’ve got four films on the docket: Monsoon Shootout; The Unknown Known, Errol Morris’ latest documentary, about Donald Rumsfeld; Ragnarok, which, if you remember, I was meant to see a few days ago; and Why Don’t You Play in Hell? One more day. One day more. Bring it on.