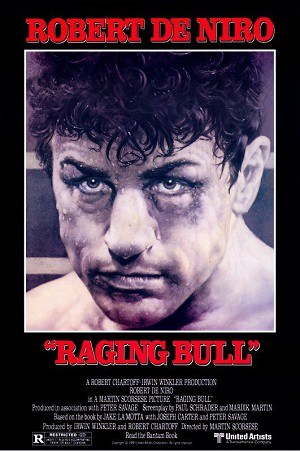

Martin Scorsese’s Raging Bull—oft-cited these days as the director’s magnum opus— first premiered in New York on November 14, 1980 to a volley of mixed reviews. At least, that’s what the Internet would have modern researchers believe. Now, 35 years later, digging up a negative review of this not-quite-a-sports-movie, not-quite-a-bio-pic seems limited to a shallow dig by Variety critic Joseph McBride, who wrote that Scorsese “excels at whipping up an emotional storm but seems unaware that there is any need for quieter, more introspective moments in drama.” Meanwhile, a glance at Rotten Tomatoes’ records show that 98 percent of contemporary critics have showered Raging Bull with praise, and even Roger Ebert, reviewing in 1980, rejects McBride’s view, awarding four stars to a film that does “a fearless job of showing us the precise feelings of their central character, the former boxing champion Jake LaMotta.”

Martin Scorsese’s Raging Bull—oft-cited these days as the director’s magnum opus— first premiered in New York on November 14, 1980 to a volley of mixed reviews. At least, that’s what the Internet would have modern researchers believe. Now, 35 years later, digging up a negative review of this not-quite-a-sports-movie, not-quite-a-bio-pic seems limited to a shallow dig by Variety critic Joseph McBride, who wrote that Scorsese “excels at whipping up an emotional storm but seems unaware that there is any need for quieter, more introspective moments in drama.” Meanwhile, a glance at Rotten Tomatoes’ records show that 98 percent of contemporary critics have showered Raging Bull with praise, and even Roger Ebert, reviewing in 1980, rejects McBride’s view, awarding four stars to a film that does “a fearless job of showing us the precise feelings of their central character, the former boxing champion Jake LaMotta.”

Fearless though it was in the characterization of its violent antihero, Raging Bull almost never made its way to the screen at all, mostly thanks to Scorsese’s own doubts when the idea was first pitched by his friend and coworker, Robert De Niro.

De Niro, who had already starred in Scorsese’s Mean Streets and Taxi Driver, put himself up for the role of Jake LaMotta after reading the real-life boxer’s poorly-written but nonetheless interesting memoir and showing it to the director, who was not impressed. Famously dispassionate toward sports, Scorsese claimed he had no idea what the story was about, while future co-screenwriter Mardik Martin said that the plot—“a fighter who has trouble with his brother and his wife and the mob is after him”—had already been done a hundred times before.

Martin Scorsese directs Robert De Niro in Raging Bull.

But everything changed when Scorsese, who had been going through a depression in his career and personal life, nearly died in New York after overdosing on prescription medication and cocaine. De Niro visited him in the hospital and decided that the time had finally come when his friend, at the lowest low of his life, might finally understand the similar pains at the center of Raging Bull. So he pitched the adaptation again and Scorsese agreed to team up, reflecting later in his own words, “I couldn’t understand Bob’s obsession with it, until, finally, I went through that rough period of my own.”

Raging Bull is, after all, more of a dramatic Shakespearean tragedy than a sports flick, and even manages to self-identify the superiority of this approach in De Niro’s opening monologue. De Niro, 50 pounds heavier as an older LaMotta rehearsing for his post-boxing career one-man show, practices in front of a mirror:

“And though I’m no Olivier,

If he fought Sugar Ray

He would say

That the thing ain’t the ring, it’s the play.

So give me a stage

Where this bull here can rage,

And though I could fight

I’d much rather recite.

That’s entertainment.”

Even the film’s groundbreaking cinematographer, Michael Chapman, referred to the piece as an opera, viewing each boxing sequence an aria. Indeed, the opening credits scene in Raging Bull—arguably one of the most beautiful openings in cinema—plays Pietro Mascagni’s Cavalleria Rusticana over De Niro’s slow motion jabs and water-like robes in the misty landscape of the ring.

What Chapman and editor Thelma Schoonmaker did for the artistry of shots like these have since been hoisted as some of the finest decisions ever put to film (Schoonmaker would win an Oscar for her work, alongside De Niro’s Best Actor). They are exactly the introspective moments overlooked by McBride, the kind that give the film an unexpected elegance that transcends the brutality of boxing.

But this elegance and forethought still appear in some of the most terrifying scenes in the film, like the in-ring, over-the-shoulder, point-of-view shots of LaMotta facing off against Sugar Ray. Along with Chapman’s heart-pounding cinematography and Schoonmaker’s breath-snatching cuts, sound effects editor Frank Warner also crafted a nightmarish atmosphere of animal noises from elephants and horses, braying with the fighters’ punches, charges, and grunts in fearsome dehumanization. In a 180-degree turn for realism, Scorsese used the real audio commentary from LaMotta and Sugar Ray’s real-life matches to play during fight scenes, and LaMotta’s actual cornerman can be seen talking to De Niro between rounds. In other boxing scenes, the lights of cameras flash like electric sparks, or else glimmer like phantoms in smoky darkness, achieved by using flames in place of glass bulbs to create a wind-stricken impression of hell.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t34MZ-Zub9c

And a hellscape it is, from De Niro’s emotionally illiterate LaMotta to Joe Pesci’s turn as his rib-smashing brother, and especially in the hard stoicism of LaMotta’s young and battered wife, played with gravity by Cathy Moriarty. A prime example of the Freudian psychology ogled by Hollywood throughout the 40s and 50s—the main time frame in which Raging Bull takes place—LaMotta is a man defined by sexual jealousy, and the Madonna-whore complex he places upon his wives, as well as his distorted views of masculinity, contain him in a state of fury.

But Scorsese didn’t want viewers to feel the need to explain LaMotta with psychology or charts of cause-and-effect. As told by the Chapman’s up-close-and-personal cinematography and the unsentimental script, LaMotta and his cohorts’ behavior isn’t intended to be dissected and explained, but rather is intended to make the audience feel the reality of being troubled, being beaten, and of self-inflicted defeat. In fact, only one voice is ever heard off-screen during the film, the only voice that enters the solitary confinement of LaMotta’s mind, and it belongs to his next door neighbor who overhears LaMotta’s domestic abuse and yells, “You’re an animal!”

Robert De Niro and Joe Pesci on the set of Raging Bull.

These moments prolong the movie, making sure each phase of LaMotta’s life feels as uncomfortable for the viewer as the next, but Scorsese makes sure to soften the blow with a little humanism that goes along way. Toward the end of the film, LaMotta, no longer a champion and locked in a real cage—a jail cell—for fraternizing with underage girls at a bar, beats his head against the walls and screams and shouts, only to cease with a whimper. “I am not an animal,” he says.

The beats of the screenplay are familiar, as Mardik Martin said. LaMotta is a middleweight boxer with dreams of becoming one of the greats. Uneducated and uninterested in much else, he uses his physical strength to abuse women and his brother, and to compensate for the affection he neither feels nor receives. He fights. He wins some, he loses some. His brother’s ties to the Mafia eventually constrict the authenticity of his career, and he winds up in a jail as a failed boxer and a divorcee with nothing much to cherish.

Robert De Niro as Jake LaMotta and Cathy Moriarty as Vickie LaMotta.

But the close of the film, a continuation of the opening scene wherein LaMotta rehearses in his dressing room, portrays best of all the beautiful rendition of a life too late regretted. Staring at his tired reflection in the mirror, LaMotta recites Marlon Brando’s monologue from On the Waterfront, this time like a ghost’s prayer at his own tombstone:

“You was my brother, Charley, you shoulda looked out for me a little bit. You shoulda taken care of me just a little bit instead of making me take them dives for the short-end money. I coulda had class. I coulda been a contender. I coulda been somebody, instead of a bum, which is what I am, let’s face it. It was you, Charley. It was you, Charley.”