When Jane Russell died at home earlier this week at the age of 89 from respiratory failure, it was the passing of a Hollywood myth. Not a legend, but a myth, for the Jane Russell we remember, the images of Jane Russell we carry in our heads, were wholly Hollywood magic: making us believe in something that wasn’t really there. Consider: Russell’s obits all use the same words — “sex symbol,” “provocative,” “sensual,” “pinup girl.” For the viewing public, she was all these things, and that was Hollywood smoke-and-mirrors at its best, for the woman behind the image that steamed up camera lenses and burned through movie screens and left many an American male tossing and turning restlessly in his bed after a night at the movies was, in the end – as they used to say in her day – a good girl.

Without taking anything away from her, that she is so well-remembered at all is a triumph of Hollywood imagery over substance. She was sold as a sex pot and though inarguably voluptuous, she was – on close inspection – attractive but not overly so. She had only a moderately long career, was making only a few sporadic film appearances by the 1960s, her last in Darker Than Amber (1970), before she walked away from movies for good. Few of her nearly two dozen films are particularly memorable, and in that strange, weird way peculiar to Hollywood, the film which launched her career – The Outlaw (1941) — is remembered more for forever defining her as a Movietown sex goddess than for being any good.

Without taking anything away from her, that she is so well-remembered at all is a triumph of Hollywood imagery over substance. She was sold as a sex pot and though inarguably voluptuous, she was – on close inspection – attractive but not overly so. She had only a moderately long career, was making only a few sporadic film appearances by the 1960s, her last in Darker Than Amber (1970), before she walked away from movies for good. Few of her nearly two dozen films are particularly memorable, and in that strange, weird way peculiar to Hollywood, the film which launched her career – The Outlaw (1941) — is remembered more for forever defining her as a Movietown sex goddess than for being any good.

Even the truth of her can read like a hackneyed Hollywood fable. Though she had been going to drama school, she was discovered by that most eccentric of eccentric billionaires, Howard Hughes, working as a receptionist for his dentist. Despite her never having been in front of a movie camera, Hughes immediately cast her as the female lead in his production of The Outlaw, a highly highly-fictionalized Billy the Kid tale. When strong-willed director Howard Hawks tired of Hughes’ constantly meddling, he walked off the picture and Hughes himself took the reins which, according to Russell, resulted in a marathon nine-month shoot – and an even longer marathon to get the movie in front of a paying audience.

In Hughes’ hands, the movie didn’t feature Russell as much as it featured Russell’s undeniably eye-catching physical  endowments. One of America’s great oddballs was so impressed with them, he designed a special seamless “cantilever bra” to further enhance his leading lady (which she claimed she never wore; a secret she says she kept from Hughes). Hollywood censors were also impressed with her, ahem, gifts (it was impossible not to; they’re the center of focus in nearly every scene she’s in), but not in a good way. Though the movie would barely rate a PG today, in its time it was considered too steamy for release, and Hughes wound up battling with censors for two years before managing to gain the film even a limited distribution, and it wouldn’t be until 1946 – five years after its completion – that The Outlaw would finally gain wide release.

endowments. One of America’s great oddballs was so impressed with them, he designed a special seamless “cantilever bra” to further enhance his leading lady (which she claimed she never wore; a secret she says she kept from Hughes). Hollywood censors were also impressed with her, ahem, gifts (it was impossible not to; they’re the center of focus in nearly every scene she’s in), but not in a good way. Though the movie would barely rate a PG today, in its time it was considered too steamy for release, and Hughes wound up battling with censors for two years before managing to gain the film even a limited distribution, and it wouldn’t be until 1946 – five years after its completion – that The Outlaw would finally gain wide release.

Russell would not appear in another movie during all that time, yet she was a star and a sex icon before The Outlaw hit screens. Crazy or not, Hughes understood the movie’s selling point was its very taboo-ness. During the time it was banned, the billionaire shrewdly built up interest in the film by marketing the hell out of it which he did by marketing the hell out of Russell. According to the actress, “…Howard Hughes had me doing publicity for (The Outlaw) every day, five days a week for five years.”

And, like much of the movie, most of The Outlaw’s relentless promotion centered around the two real stars of the film: Jane Russell’s breasts. Garson Kanin once wrote about walking along Broadway with George S. Kaufman and passing no less than five billboards for the movie featuring Russell with peeping cleavage and come hither gaze. Kaufman’s reaction: “They ought to call it, A Sale of Two Titties.”

And that would be the prism through which Russell would be viewed throughout much of her career, although every so often she would catch a role showing there was more to her than a healthy set of curves. She was a capable tough-gal foil for lily-livered Bob Hope in the Western farce, The Paleface (1948), and in her best film, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953), she sang, danced, charmed, made funny, and easily held her own against the Death Star of sex bombs: Marilyn Monroe.

The bulk of her movie career, however, was rather undistinguished although if anyone was bothering to look past her décolleté, they’d have been able to see that while she wasn’t a great actress, she could hold the screen against some impressive presences. She did two films playing opposite Robert Mitchum, the best of which is the delicious mess, His Kind of Woman (1951). Like Mitchum, she came across with an attractive blend of sexiness and toughness, not unwilling but picky. Where Monroe came across as a whispery fragile flower playing against Mitchum in The River of No Return (1954), Russell stood her ground, matched him bedroom eye for bedroom eye and a look that said, “Well, maybe if you’re a good boy…”

The bulk of her movie career, however, was rather undistinguished although if anyone was bothering to look past her décolleté, they’d have been able to see that while she wasn’t a great actress, she could hold the screen against some impressive presences. She did two films playing opposite Robert Mitchum, the best of which is the delicious mess, His Kind of Woman (1951). Like Mitchum, she came across with an attractive blend of sexiness and toughness, not unwilling but picky. Where Monroe came across as a whispery fragile flower playing against Mitchum in The River of No Return (1954), Russell stood her ground, matched him bedroom eye for bedroom eye and a look that said, “Well, maybe if you’re a good boy…”

She showed the same tough-but-sexy moxy in the Western (1955) with Clark Gable. Russell’s Nella Turner would never have stood for being whisked up a set of stairs to the boudoir the way Gable had done with Vivien Leigh in Gone with the Wind (1939). More likely, she would have kicked him in the nuts, then stood over his writhing body telling him, “When I say; not you!”

In one way, she was a better actress than most thought because she made it all so convincing…and it was as removed  from her true self as the sun from the moon. She may have played the loose-hipped sex bomb in the movies or when guest appearing on TV, but she managed something in her decades in Hollywood few other Tinsel Town pinup queens managed then or since: a scandal-free life. Her first marriage was to her high school sweetheart and it lasted 24 years. Privately, she was a devout Christian reading the Bible every day, held Bible studies in her home, recorded gospel records, and founded the World Adoption International Fund which placed over 51,000 kids with adoptive families.

from her true self as the sun from the moon. She may have played the loose-hipped sex bomb in the movies or when guest appearing on TV, but she managed something in her decades in Hollywood few other Tinsel Town pinup queens managed then or since: a scandal-free life. Her first marriage was to her high school sweetheart and it lasted 24 years. Privately, she was a devout Christian reading the Bible every day, held Bible studies in her home, recorded gospel records, and founded the World Adoption International Fund which placed over 51,000 kids with adoptive families.

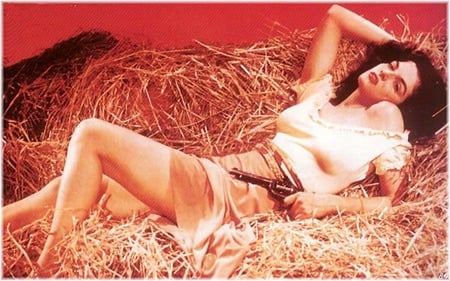

That’s the magic of Hollywood, the kind of dream-making the Dream Factory has excels at. Jane Russell will always be remembered laying back on a bed of straw, dress slipping off her shoulder revealing a bit of cleavage, hair tousled, looking as if she’s just had a roll in the hay and is ready for another. But behind the sultry gaze and dark, kissable lips she was a good girl.

– Bill Mesce