It’s tax time, so what better time to talk money?

Sky-high budgets, costly marketing blitzes, revenues siphoned off by profit participants – it’s never been harder for a studio to make back its ever-increasing outlays. Even with sharp increases in ticket prices, recoupment for a studio is anything but assured. In 1990, the average movie’s production cost ($18.1 million) stood at more than four million times the price of the average admission ticket ($4.11); just ten years later, the proportion grew almost three-fold, to better than 11 million times, despite an approximately 13% hike in the average ticket price ($52.7 million/$4.69). This, in turn, has forced a drastic evolution not only in how studios attempt recoupment, but the financial dynamic which occurs in every multiplex and its direct impact on the consumer.

More simply: we’re going to answer the question of why you need a second mortgage to buy a king-sized Coke and a bucket of popcorn.

The transformation of exhibition from a circuit of primarily single-screen auditoriums to today’s multiplex-dominated environment was a move on the part of exhibitors to build themselves a cushion against weak-performing flicks. Multi-screen theaters had been around since the 1930s, but the concept flourished in the 1980s, piggy-backing on the explosive growth of suburban shopping malls and plazas which often incorporated a movie theater.

The concept was always very simple. A plex theater’s fortunes didn’t live or die week-to-week with the strength/weakness of the feature on any one screen. Multiple screens meant a dud on one screen could be offset by a hit on another. Advances in automated projection technology eliminated the need for projectionists and made multiplex operations highly cost-efficient (it is also, however, the reason that finding a plex staffer who can fix a projection problem has turned into such a monumental task for patrons; back in The Day, a simple disgruntled yell of, “Focus!” aimed at the projection booth used to suffice).

As Hollywood became more addicted to the outsized box office possibilities of big budget blockbuster flicks, multiplex operators saw an opportunity to maximize their gate by ironically offering fewer choices and running heavily-hyped major releases on multiple screens, particularly during the first weeks of release.

The payoff in doing so, however, wasn’t in the money earned at the box office which – even with monster hits – isn’t what you’d think it might be.

Ever since the 1948 decrees separating studios from their theater chains, box office receipts have been split between exhibitor and distributor. Typically, approximately 45% of a venue’s box office goes to the exhibitor. For blockbusters, though, the studios have – by necessity – imposed a harsh change in the formula, one based on a sliding scale in which, during the early part of the run, the overwhelming bulk of the box office goes to the distributor, with the percentage gradually swinging toward the exhibitor with each passing week.

As recently as the 1990s, studios had been demanding extended minimum-run commitments from exhibitors on major releases. George Lucas, for example, exacted 12-week guarantees from exhibitors wanting to screen Star Wars: Episode 1 – The Phantom Menace (1999). What made such a demand digestible to exhibitors was the belief that the movie would continue to perform well enough weeks into its run to provide the theater with an eventual pay-off for its commitment.

As recently as the 1990s, studios had been demanding extended minimum-run commitments from exhibitors on major releases. George Lucas, for example, exacted 12-week guarantees from exhibitors wanting to screen Star Wars: Episode 1 – The Phantom Menace (1999). What made such a demand digestible to exhibitors was the belief that the movie would continue to perform well enough weeks into its run to provide the theater with an eventual pay-off for its commitment.

In most cases, however, today’s foreshortened box office arcs have distributors asking for as much as 80-90% of gross ticket revenue during the biggest-earning opening weeks with the percentage not swinging toward the exhibitor’s favor until a movie’s drawing power is well – and quickly — on the wane (major releases typically earn as much as 50-75% of their total take by their third weekend in release, with receipts dropping by approximately a half or better week-to-week). As one studio executive put it, “When you know that there’s another blockbuster a week behind you, you want to earn as much as you can as quickly as you can.” With such one-sided box office splits, the exhibitor usually operates his blockbuster-dedicated auditorium at a loss, with only a slim chance the picture will still be throwing off enough revenue after the box office split turns in his favor to be profitable for the venue.

The most obvious and predictable effect of this dynamic at the exhibition level has been a boost in ticket prices well  above the rate of inflation. In 1963, the average ticket price was $.83; twenty years later, it stood at $3.15; in 2007, $6.74; today, somewhere around $7.50, and typically over $10 in theaters charging extra for 3-D screenings. In some major urban markets, like New York City for example, base ticket prices have been over $10.00 for several years. Still, even as ticket prices continue to climb, with an exhibitor turning over 80% of the gate to the distributor, the theater-retained 20% is still only enough, at best, to moderate an exhibitor’s loss rather than generate a significant profit.

above the rate of inflation. In 1963, the average ticket price was $.83; twenty years later, it stood at $3.15; in 2007, $6.74; today, somewhere around $7.50, and typically over $10 in theaters charging extra for 3-D screenings. In some major urban markets, like New York City for example, base ticket prices have been over $10.00 for several years. Still, even as ticket prices continue to climb, with an exhibitor turning over 80% of the gate to the distributor, the theater-retained 20% is still only enough, at best, to moderate an exhibitor’s loss rather than generate a significant profit.

Unsurprisingly, then, theater managers have turned to a variety of tactics to augment their revenues. Strategies include offering auditoriums for meeting rentals, hosting children’s birthday parties, and, most visibly, providing a venue for advertising. As part of their film program, as well as appearing on-screen between scheduled features, multiplexes are turning over increasing amounts of screen time to local and national advertising. One newspaper account of multiplex advertising in New Jersey venues clocked five-six minutes of advertising as a typical part of the feature program on top of the interstitial time given over to slide ads. While many moviegoers may rankle at being a captive audience for multiplex advertising, “The majority of theaters,” says one small theater chain operator in New Jersey, “are doing it because it does help defray costs.” According to the National Association of Theater Owners, on-screen advertising is a necessary tool for theaters to “…keep ticket prices affordable…” (although as ticket prices continue to climb, one wonders about NATO’s idea of “affordable”). By the middle of the first decade of the 2000s, movie house advertising had become a $300 million a year business, with two-thirds of the U.S.’ 36,000 screens showing ads. By 2009, the theater take from ads was up to $584 million.

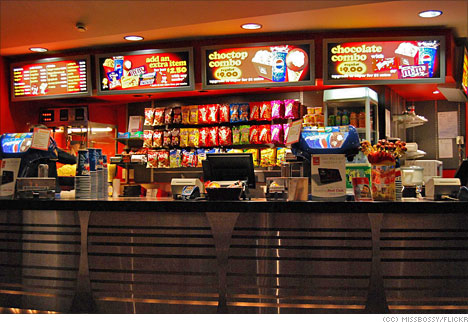

The biggest revenue-generator for exhibitors, however, is not the box office nor its on-screen advertising business, but the area of concessions. In effect, as big-budget blockbusters have steered studios from the movie-making business into the event-hyping business, the studios’ lopsided box office splits have steered movie theaters from the movie exhibiting business into the snack food vending trade.

Some theaters have gone one step further, turning a visit to the multiplex into an exercise in (sometimes) fine dining as well…with prices to match. AMC Theatres has rolled out their Cinema Suite concept at a few locations in Kansas, Texas, and New Jersey. Your $30 admission (that’s right; thirty bucks…apiece) gets you a non-refundable $20 food coupon with your ticket, an auditorium with reclining leather seats, and attendants serving you everything from a traditional popcorn-and-soda movie nosh to a full dinner from the house menu. Other exhibitors – the Academy Theater in Portland, Oregon; the Alamo Drafthouse with locations in Texas and Virginia; the Theatres at Canal Place in New Orleans — offer similar evolutionary leaps in the concessionary arts with offerings ranging from cocktails and local microbrews (the Academy) to a Mediterranean-flavored menu put together by a gourmet chef (the Theatres at Canal Place). In most cases, combining dinner and a movie into a one-stop event including $8.75 Tanqueray gin and Cointreau cocktails (Seattle’s The Big Picture) and $18.50 churrasco steaks (Miami’s Cinebistro) can easily run up the tab for a couple’s movie night close to three digits. The price of a family night out? Bring some collateral with you.

At the risk of seeming curmudgeonly nostalgic, it does seem there was a time when people went to the movies to see a movie. Snacks were, well, just that: snacks. Something to hold you over until the movie was over.

But, in an era of declining attendance and one-sided receipts splits, exhibitors seem to be turning the movie part of going to the movies into an afterthought.

“Your drinks, madam, sir.”

“Oh, why thank you. Mmm, these are quite good!”

“Thank you. Your dinner will be out in a moment. The movie starts in five minutes.”

“Oh, we get a movie, too? Fancy that! What’ll they think of next?”