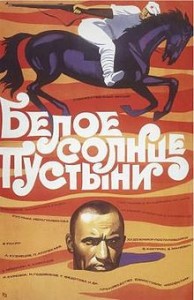

White Sun of the Desert

Written by Valentin Ezhov, Rustam Ibragimbekov, Mark Zakharov

Directed by Vladimir Motyl

Soviet Union, 1969

The glimmering cupola on a fondly named Borscht Western chapel, Vladimir Motyl’s 1969 film White Sun of the Desert is a telling contrast to its compatriot Spaghetti Westerns, as it chronicles a few peculiar events of civil war on the Caspian Sea through the eyes of Red Army soldier Fyodor Sukhov (Anatoli Kuznetsov). The film quickly became an unofficial national treasure, though its statements are offered through the hushed humour of sometimes farcical, often philosophical, performance.

This is a tale of one man stranded on the cusp between a war and his home, his capers peppered by the letters he faithfully scribes to his wife. It is no incidental matter that Fyodor Sukhov’s memories hold a staunch grip on the alabaster skin and scarlet cloth that swathes Katerina Matveyevna (Galina Luchai).

With her voluptuous figure, unwavering gaze of arctic ice, and succulent hues of red flushed against the grace of birch trees, Katerina exemplifies a Russia that fills the dreams of every wayfarer longing for home. She is a rosy-cheeked embodiment of Arkady Plastov’s romanticized villages and Maxim Gorky’s pastoral scenes painted with simple words for the richest imaginations of children. Her sturdy body brims with maternal plenitude and the longing for her embrace is one that laces the tender verse of Sergei Yesenin. Perhaps the significance of Katerina’s image falls into that unique phenomena of cinematic iconography that becomes all the more striking with distance and time.

With her voluptuous figure, unwavering gaze of arctic ice, and succulent hues of red flushed against the grace of birch trees, Katerina exemplifies a Russia that fills the dreams of every wayfarer longing for home. She is a rosy-cheeked embodiment of Arkady Plastov’s romanticized villages and Maxim Gorky’s pastoral scenes painted with simple words for the richest imaginations of children. Her sturdy body brims with maternal plenitude and the longing for her embrace is one that laces the tender verse of Sergei Yesenin. Perhaps the significance of Katerina’s image falls into that unique phenomena of cinematic iconography that becomes all the more striking with distance and time.

Far across the bleak desert landscape, Sukhov seems to amble effortlessly through skirmishes and bizarre encounters that impede his journey homeward. He is, ultimately, an idealized man, single-handedly overcoming all enemies with heroic composure. Roving bands of Basmachi guerillas and accompanying Red Army traitors send no tremors across the soldier’s resolute persona. Sukhov’s simplicity and stubbornness is in fact more characteristic of an adolescent boy, akin to the legendary Soviet pioneer scouts, than the war-weathered man he could be. In effect, he is too good of a soldier, too willing and devoted, to be the rōnin we quietly hope to find beating in his eroding white uniform.

No doubt, White Sun of the Desert throbs with a partisan propaganda cloaked in youthful dreams of adventure and deeply instilled cultural imagery. Following the initial directorial rejection of the film by Andrei Tarkovsky and Andrei Konchalovsky, director Vladimir Motyl created a film devoid of the overt brutality of combat to which western audiences are most accustomed. Liberal romanticism of civil war or not, White Sun of the Desert sustains the warmth of a surreal magic through the story’s whimsy and naivety. Touched by the soothing familiarity of folklore, the pace is about as sprawling as the sea-washed desert, which gives the film a relaxed, if not tranquilizing texture.

Though tinged with an essence of the surreal, the film never feels like a still-life, inorganic in a staged being. On the contrary, the lyrical progression of Fyodor Sukhov’s adventures from one obscure situation to another seems only natural. There are a number of instants throughout the film that tease as superficially irrelevant, yet combine to form a shuffling juxtaposition of the solemn and the overtly comic. As a result, the film exudes an eccentric method of telling a story that otherwise seems to lack the substance viewers might expect from stories of war. Revisiting it today reveals a poignant contrast to the glamorized brutality expected of war films, and transports us into the magical mind of a resilient and romantic man.

Though tinged with an essence of the surreal, the film never feels like a still-life, inorganic in a staged being. On the contrary, the lyrical progression of Fyodor Sukhov’s adventures from one obscure situation to another seems only natural. There are a number of instants throughout the film that tease as superficially irrelevant, yet combine to form a shuffling juxtaposition of the solemn and the overtly comic. As a result, the film exudes an eccentric method of telling a story that otherwise seems to lack the substance viewers might expect from stories of war. Revisiting it today reveals a poignant contrast to the glamorized brutality expected of war films, and transports us into the magical mind of a resilient and romantic man.

White Sun of the Desert has not only garnered a religious following over the years, it has become an indispensable ritual for Russian cosmonauts before boarding their flights. This comes as no surprise with the film’s palpable nostalgia for home harmonized by the balalaika serenades that croon over an alien Central Asian desert. The plainness and sentimentality with which White Sun of the Desert has been told, and which stands at the core of many Soviet films, may seem easy to dismiss for audiences accustomed to contemporary cinematic blatancy. On the other hand, those who are chronically accused of reading too far between the lines can find gentle respite in the spaces this film leaves for imagination.

– Lital