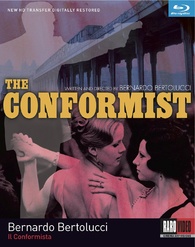

The Conformist

The Conformist

Written and directed by Bernardo Bertolucci

Italy, 1970

When first introduced to the improved quality of Blu-ray technology, there were about a dozen films I couldn’t wait to see in the format. These were movies of extraordinary beauty that I knew would surely benefit from the enhanced visual resolution. Now, with the arrival of Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Conformist on a stunning new Raro Video edition, another one of those titles can be scratched off the list. What makes this an exciting release, however, goes beyond the look of the picture (though that is paramount). This is, in every regard, one of the greatest films ever made.

The Conformist is a complex chronicle of the tormented, ruthless, and devious Marcello Clerici (Jean-Louis Trintignant), a rising-through-the-ranks Fascist enforcer. The film is a fascinating look at the extent to which one will go to escape the past, fit in with the present, and secure a place in the future. Clerici is the embodiment of repression: repression of heartfelt desire, emotion, everything except ambition. He’s about to wed Giulia (Stefania Sandrelli), a simple-minded petty bourgeois whom he dismisses as “mediocre” and “all bed and kitchen.” Even Giulia’s mother thinks her daughter is not worthy of Clerici. The marriage would be a sham; it’s not at all about love. Yet, for him, the union is a necessity. In his eyes, marriage is about normalcy, stability, and security. More than anything else, Clerici wants to be like everyone else. When a friend asks him what a normal man is like, he responds, “He likes people similar to himself and does not trust those who are different.”

Clerici is given an assignment that should be easy enough and would do a good deal to establish himself as a vital political soldier. He is to travel to Paris and reconnect with his former anti-Fascist professor, Quadri (Enzo Tarascio), and determine who the old man’s subversive contacts are back in Rome. Shortly thereafter, counter orders instruct Clerici to simply kill Quadri. But the mission becomes complicated when Clerici falls for Quadri’s wife, Anna (Dominique Sanda); this despite the fact that Giulia has accompanied him on his trip to France.

With the moral crisis of Clerici’s romantic involvement is a political crisis that likewise compromises his responsibilities, and the two are never entirely disconnected. He instructs his driver and Fascist associate Manganiello (Gastone Moschin) to place country before family, yet he is quickly willing to drop everything and go to Brazil with Anna. Indeed, she is a formidable beauty, with more than a hint of danger. One particularly striking shot has her seductively striding toward the camera, thumbs in her pockets; she poses enticingly in the doorway then lounges nonchalantly in a chair. Though she had earlier embraced Clerici, she later stares him down as she similarly flirts with his nude fiancé. The provocative sexual tension between her and Clerici as well as between her and Giulia (to say nothing of her apparent fondness for her husband) leave one to wonder what exactly her angle is in the whole enterprise. In any case, this interior rupture leaves Clerici in a perpetual state of discomfort, his pent up angst only occasionally given some levity in oddly quirky behavior.

With the moral crisis of Clerici’s romantic involvement is a political crisis that likewise compromises his responsibilities, and the two are never entirely disconnected. He instructs his driver and Fascist associate Manganiello (Gastone Moschin) to place country before family, yet he is quickly willing to drop everything and go to Brazil with Anna. Indeed, she is a formidable beauty, with more than a hint of danger. One particularly striking shot has her seductively striding toward the camera, thumbs in her pockets; she poses enticingly in the doorway then lounges nonchalantly in a chair. Though she had earlier embraced Clerici, she later stares him down as she similarly flirts with his nude fiancé. The provocative sexual tension between her and Clerici as well as between her and Giulia (to say nothing of her apparent fondness for her husband) leave one to wonder what exactly her angle is in the whole enterprise. In any case, this interior rupture leaves Clerici in a perpetual state of discomfort, his pent up angst only occasionally given some levity in oddly quirky behavior.

The planned assassination is further hindered when Anna unexpectedly travels with her husband on the morning he is to be killed, and Clerici has already been told there can be no witnesses to the murder. The eventual confrontation along an isolated forest road is cold and calculated, yet it erupts with a chaotic violence. Amidst the serenity of the towering trees, the wind, the snow-covered mountainside, Clerici becomes stoic in the face of his obligation and his inscrutable emotions, thus forcing others to give chase as Anna flees. Bertolucci employs a frantic handheld camera that conveys the desperation of not only those pursing the young woman but of her own tragic plight.

Coupled with Bertolucci’s canted angles, elaborate camera movements, and static compositions of notable balance, Vittorio Storaro’s gorgeous Technicolor cinematography gives The Conformist its visual novelty, which is probably the film’s most pronounced attribute. The mélange of colors at a party (ironically attended primarily by blind people) contrast with the starkness one associates with the Fascist regime. At times, the opposed hues of bold colors and industrial blandness will also unify in a single image, as when a somber cityscape at dusk is shot through by piercing yellow headlights. In the same way, the vast echo chambers that comprise the regime’s office buildings are barren, grey, sterile, and generally unadorned facilities. Certain domestic interiors, on the other hand, are a mergence of illumination, costume, and set design; Giulia’s black and white striped dress mirrors and blends with the horizontal shafts of sunlight coming in the partially open blinds, for example. Throughout the film, every scene — nearly every shot — is a dazzling play of light and color, texture and movement.

Coupled with Bertolucci’s canted angles, elaborate camera movements, and static compositions of notable balance, Vittorio Storaro’s gorgeous Technicolor cinematography gives The Conformist its visual novelty, which is probably the film’s most pronounced attribute. The mélange of colors at a party (ironically attended primarily by blind people) contrast with the starkness one associates with the Fascist regime. At times, the opposed hues of bold colors and industrial blandness will also unify in a single image, as when a somber cityscape at dusk is shot through by piercing yellow headlights. In the same way, the vast echo chambers that comprise the regime’s office buildings are barren, grey, sterile, and generally unadorned facilities. Certain domestic interiors, on the other hand, are a mergence of illumination, costume, and set design; Giulia’s black and white striped dress mirrors and blends with the horizontal shafts of sunlight coming in the partially open blinds, for example. Throughout the film, every scene — nearly every shot — is a dazzling play of light and color, texture and movement.

The narrative disjunction of The Conformist, with multiple flashbacks spanning almost Clerici’s entire life, is additionally compounded due to the film’s abrupt shifts in pace and editing, with brief shots countered by longer takes, frontal camera positions next to extreme high and low angles, sweeping crane shots next to a stationary, restrained distance. Bertolucci, a devout disciple of Jean-Luc Godard, infuses The Conformist with several instances of Godardian juxtaposition, and in Adriano Apra’s visual essay, which accompanies this disc and primarily consists of an interview with Bertolucci, the critic  breaks down via graphs and diagrams the film’s patterns of camera movement, scene duration, and narrative chronology. But while Godard’s experimentation was often integrated as a self-consciously formal approach to cinematic aesthetics, Bertolucci’s choices are arguably more character-driven, with the disparity of stylistic forms echoing the inconsistency of Clerici’s principles and yearnings. (In another Godard connection, Alberto Moravia, who wrote the novel upon which The Conformist was based, also penned “Il Disprezzo,” the source for Godard’s Contempt, 1963.)

breaks down via graphs and diagrams the film’s patterns of camera movement, scene duration, and narrative chronology. But while Godard’s experimentation was often integrated as a self-consciously formal approach to cinematic aesthetics, Bertolucci’s choices are arguably more character-driven, with the disparity of stylistic forms echoing the inconsistency of Clerici’s principles and yearnings. (In another Godard connection, Alberto Moravia, who wrote the novel upon which The Conformist was based, also penned “Il Disprezzo,” the source for Godard’s Contempt, 1963.)

Had this style been The Conformist’s sole distinguishing feature it would still be significant, but there is an equal substance that gives the film its historical, social, and psychological resonance. This is primarily achieved through Bertolucci’s inspection of Clerici, his troubled youth, his policy-driven aspirations, and his deep-seeded, unspoken motivations. A homosexual experience with an older chauffeur at the age of 13 led him to a shocking act of violence, and the event has never left him. Its lingering impact is a result of the guilt of the encounter and/or the feelings that remain and may not ever quite subside. His father, equally political in his own time, is now confined to a mental institution. (An anonymous letter writer contends the insanity is a result of syphilis and may be hereditary; Clerici assures Giulia he has only ever suffered “moral maladies.”) And his haggard and drug-addled mother may or may not be having an affair with her Japanese driver, who may or may not be providing her with the morphine. Clerici wants little to nothing to do with these personal demons and familial failings. These things stand out. Clerici wants to blend in. He wants to be just another Fascist suit and hat that tows the party line. Despite some of his half-hearted romantic actions, he exudes contempt for drama and passion.

As a face to 1930s/40s Italian Fascism, Marcello Clerici is something of an exception to the normal portrayal of similar individuals. Far from the depraved caricatures of Pasolini’s Salo (1975), for example, Clerici is actually a fully-formed and complex character. He is more than merely a brutal one-dimensional killer. He has a back-story, however ambiguous; he has a personality, however insipid; and he has his reasons, however indefinite. Most prominently, as seen in shots like that behind the opening credit scrawl or in the enigmatic close-ups of his face as he and Manganiello drive toward the woods, Clerici conveys a capacity for introspection. While he may make a mockery of confession, there can be no denying that his past deeds weigh heavily on his current state, and by the end of the film, shocking realizations about those very deeds send him reeling in genuinely emotional distress. Confronted simultaneously with the demolition of his political ideals and the truth of at least part of his personal torment, Clerici manages to emerge almost as a sympathetic individual.

As a face to 1930s/40s Italian Fascism, Marcello Clerici is something of an exception to the normal portrayal of similar individuals. Far from the depraved caricatures of Pasolini’s Salo (1975), for example, Clerici is actually a fully-formed and complex character. He is more than merely a brutal one-dimensional killer. He has a back-story, however ambiguous; he has a personality, however insipid; and he has his reasons, however indefinite. Most prominently, as seen in shots like that behind the opening credit scrawl or in the enigmatic close-ups of his face as he and Manganiello drive toward the woods, Clerici conveys a capacity for introspection. While he may make a mockery of confession, there can be no denying that his past deeds weigh heavily on his current state, and by the end of the film, shocking realizations about those very deeds send him reeling in genuinely emotional distress. Confronted simultaneously with the demolition of his political ideals and the truth of at least part of his personal torment, Clerici manages to emerge almost as a sympathetic individual.

Only Storaro’s cinematography on Apocalypse Now (1979) gives his work here some competition, and Georges Delerue’s score is only bested by his music for Contempt. The production design by Ferdinando Scarfiotti and the costumes by Gitt Magrini add to the film’s glorious whole, and the performances by all involved are excellent. Sandrelli’s innocence as a decent young woman who just wants to blindly love Clerici counters nicely against Sanda’s knowing seductress, and Trintignant, on whom the film hinges most, is a contradictory blank slate of emotion. He is almost like a walking, talking personification of Lev Kuleshov’s famous editing experiment, his surface stoicism expressing so much based on surrounding elements, shots, and sequences. Yet to register so much by doing so little shows a notable understated restraint. The Conformist followed Bertolucci’s The Grim Reaper (1962) and Before the Revolution (1964) and was released a few years before Last Tango in Paris (1972) and 1900 (1976). To say the least, he was in the midst of an exceptional period of filmmaking. At the same time though, the reason The Conformist works so well (and looks and sounds so good), has a lot to do with these key collaborators.