Ever since it was released as a mod for Half-Life 2, The Stanley Parable has been a cult phenomenon. It was never a particularly long game: play-throughs usually lasted between five and fifteen minutes. It also did nothing particularly remarkable with the graphic engine, as it mostly consisted of drab corridors and lifeless cubicles. What made it interesting was its hilarious narrator, always commenting on the player’s actions with devastating wit and piercing scorn. Now a spruced-up commercial release, with remade environments and an extended quest, the experience is still very much the same. The Stanley Parable is a game about playing games, questioning assumptions typically made by gamers and designers, especially the illusion of choice. In a digital environment, where possibilities of movement are predetermined by code, players can only do as much as they’re allowed to do. The narrator in The Stanley Parable beckons players to run through a door and ignore another, or take an elevator up instead of down, and players are compelled to misbehave. But even when they contradict the narrator and laugh at its tantrums, they are still following preordained trails. There is no escape, not even for the narrator, who is another pawn.

In a videogame, we forget the outside physical world and accept the rules of a new reality. Objects and bodies, though reminiscent of real-life counterparts, come to adopt new meanings depending on their value within the game. When the structure of this new reality is deconstructed, we are compelled to ask: if we lack freedom in a virtual context, is the same true outside of it? Who created these rules? And is there a way out? As in the mod, every agreement or disagreement with the narrator is a forking path, one direction taken instead of another. These instances add up, and so do the number of potential endings. The only happy ending, ironically, is achieved by acquiescing to the narrator’s demands. Players embody a man named Stanley, a mindless computer typist who one day wakes up to find his company premises devoid of life. As he learns, the building is actually a massive laboratory, where employees are supervised and made to press random buttons in alienating offices, while their pathetic images are broadcast to a massive and Orwellian surveillance room. The narrator helps Stanley escape the laboratory, but how can this mean freedom if players only follow orders?

The commercial release of The Stanley Parable adds so much to its predecessor, so many options and narrative permutations, that the original mod seems like a distant rough draft in comparison. In a moment of genius, in the updated version, players drop down into a deep basement level, where the darkened remnants of the mod’s crude hallways coil like the ruins of an underground city, a desolate memory of what used to be. Dear Esther, another former Half-Life 2 mod, also received a remastered commercial release, but in that case the overhaul was mostly aesthetic, as the basic layout of the game’s island remained more or less consistent. This new Stanley Parable, on the other hand, is more thoroughly reworked.

It is also rigorous and obsessive about its central ideas, more so than the mod. It perpetually loops into itself, dragging players back to the opening screen after each ending. Its self-awareness is extreme. It is even self-aware about being self-aware. The narrator, after the player discovers an unlikely broom closet, admits that The Stanley Parable is a satire of game tropes. In one of the most spectacular of the many possible endings, the same narrator discovers that even his own actions and responses are scripted, so he suffers an existential crisis. And, in another ending, players explore a startlingly bright museum, where various installations and paintings chart the game’s actual making, like a cheeky developer’s commentary. Yet, the humor is tucked underneath an informative and even serious look at the creative process. In a way, this ending is the one that most perfectly condenses the themes of The Stanley Parable. Museums are always interesting in games, because players enter a place where individual pieces of art – the objects in the virtual gallery – interact with the larger artwork that is the game itself. Older media is received passively and at a distance. Or at least, it seems that way.

In truth, watching a movie, looking at a painting, or reading a book are interactive experiences, since viewers and readers meet the works halfway, mentally shaping their reception. Videogames visualize and dramatize this interaction, realize it on the plane of a video screen. Players interact, not just through interpretation, but through movement and action inside an environment. When a museum is placed inside a game, the contrasts between old and new media are foregrounded. Players, accustomed to the interactive arenas of games, are forced to revert to passive observation. The Stanley Parable is not the first title to do this. Two classics from the 1990s include memorable gallery spaces, Planescape: Torment and The Longest Journey. More recently, Limits and Demonstrations, a demo of the ongoing serial adventure game Kentucky Route Zero, is entirely made up of such a location. As in real modern art museums, some installations straddle the line between observation and physical participation (which also happens in Planescape: Torment). Other pieces, however, are only there to be admired at and talked about with non-playable characters.

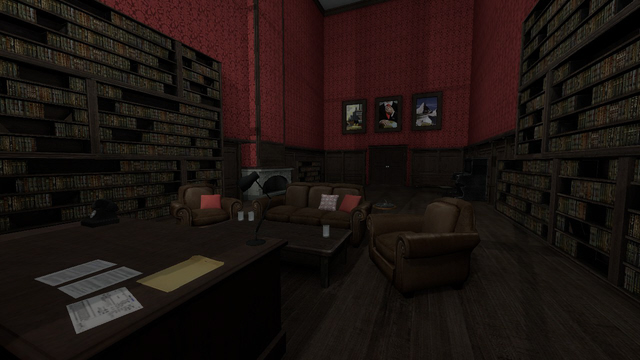

The Stanley Parable has perhaps one of the most interesting virtual museums. Not only because the exhibit concerns the game’s own conception, but because a gallery space is an appropriate metaphor to describe the vague genre of the “walking simulator,” to which The Stanley Parable could be said to belong. The most infamous example of this type of game is probably Dear Esther, which presents a mostly linear trail through an island we can only look at. No objects can be picked up, no characters spoken to, no doors opened, and almost no secrets unveiled. Players can only hike over hills and down into caves, peering at the terrain and overhearing snatches of ghostly narration. They might as well be in a museum, albeit a rather unconventional one. The Stanley Parable is the same, albeit with more choices in terms of path-finding. But as the game makes clear, these choices are meaningless. All objects scattered throughout the laboratory are fixed in place, immovable, except for one surprising area, where players are suddenly transported to a completely different game, Valve’s Portal. Because of its rules, players can actually manipulate things like radios and cubes. The effect, after enduring roomfuls of static scenery, is almost liberating. Yet we soon return to The Stanley Parable, where notebooks, papers, trashcans, brooms, and desktops stay put, and doors open and close by themselves. As in a gallery, we can see but cannot touch.

Although so-called “walking simulators” have inspired as much ire as adulation, and though many critics insist that they are not even games, they only emphasize an experience common to the medium: wandering about, gazing here and there. Some of the finest moments in otherwise unambiguous videogames, like Ico and Okami, are spent in contemplation, as the business of puzzle-solving gives way to the survey of evocative backdrops. True, in both cases, the visual draw of the environment has a pragmatic purpose: progression depends on knowing where to go next and what to do to get there. Sightseeing is not only enjoyable but fundamentally useful. Yet the backdrop is often compelling beyond this practical logic. We bask in it as we would in front of a lush canvas. More traditional paintings line the walls of castles and mansions in Thief 2, and though players can do nothing with them, their unsettling portraits, beacons of refinement and classicism in houses of danger, contribute strongly to the suspenseful mood.

The Stanley Parable and its ilk focus entirely on this dynamic, on the tension of an alluring environment that denies interaction in a medium known for it. Nevertheless, players are still the owners of their gaze. “Walking simulators” flirt with the linearity of film, but ultimately reveal themselves to be something other, because film is temporal art with preset rhythms while videogames are preset locations where players determine the rhythm of their exploration. Despite the limitations imposed by creators, there are almost always unexpected consequences. Videogame theorist David Myers, in his book ‘Play Redux’, proposes that designers cannot foresee the boundaries of their own titles. Gamers slowly and doggedly test the rules, bend them to their breaking point, redefine the meaning of game objects. One need only look at the culture of speed runners to discover how unruly players can be. Modern masters of Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time do not engage with it as Nintendo envisioned. A list of cheats has been collated over the years, not simple button presses but complicated maneuvers: from gaining speed by running backwards to changing the coded value of items so that, for instance, a bottle can become a musical instrument.

Admittedly, “walking simulators” restrain the reach of such experimentation, chaining players to a single train of interaction. The Stanley Parable simplifies its gameplay to such a degree that alternate playing styles are hardly possible. It’s a self-fulfilling prophesy: the designer is God because there is no space to prove him otherwise. Only gazing and walking, as mentioned before, remain up to individual agency. However, as the museum makes clear, crafting the game was an exercise in anticipating players and circumventing unruly behavior. Even what lies outside the narrator’s orders falls inside the intentional course of the adventure. Because of its narrow construction, The Stanley Parable cannot be about the player’s search for freedom of expression inside a digital context: there is just not that much to do. What the game can be (and is) about is to what extent players can accept directions and the reduction of their freedoms, all for the pleasure of a dramatic storyline which might even end in their false emancipation.