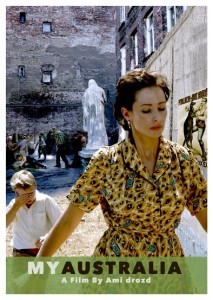

Written and directed by Ami Drozd

Israel/Poland, 2011

In the social and economic fallout that followed World War 2, ten-year old Tadek and his older brother Andrzej become victims of the decaying zeitgeist in post-war Poland. They benightedly join a gang of hooligans with neo-Nazi attitudes, but after being arrested for beating up a group of Jews, their mother reluctantly reveals their hidden Jewish history and identity.

Tadek’s mum, realizing the futility of being Jewish in Poland, resolves to move away, and, under the pretext of going to his coveted Australia, Tadek and his family sail to Israel in hopes of starting a new life.

The first half of the My Australia plays out as an intriguing combination of American History X and The Believer. As Tadek and his brother come to grips with their previously unknown heritage, they try to rationalize their past with their present, understand what it means to be Jewish, and lead a life anew, both physically and philosophically.

Some of the most touching scenes come from Tadek’s apprehension and culture shock. In particular, he adamantly refuses to take communal showers at his Kibbutz, where both boys and girls indiscriminately participate. For Tadek, people back home shower in solitary; plus, he doesn’t want to reveal to the others how he is uncircumcised. This duality in just one scene is incredibly inspired, but, unfortunately, it’s where the film slowly starts to derail.

As the film tries to complete Tadek’s inevitable character arc, My Australia loses all pretenses of narrative credibility, manifesting into a sanctimonious forgery that’s morally facile and tonally capricious.

Without spoiling the plot, the ultimate aim of the story is to show Tadek’s eventual acceptance of Jewish culture and the denunciation of his past. But in order to do so, the film takes an unscrupulously simplistic approach, providing a neat, well-packaged explanation of issues that ignore its truly deep complexities.

For example, Zvi, one of Tadek’s surrogate parents at the Kibbutz, is a Polish native who no longer speaks Polish. Later, we find out that his self-muting is in protest to his fellow Poles killing fellow Jews after the war, with his silence being a form of condemnation of his people.

The film never points out, or even acknowledges, the possibly of an outlier, nor does it attempt to explain the possible socio-economic circumstances that might have fostered this resentment. Instead, it unfairly paints Polish people in broad strokes, generalizing them all as hateful, unpleasant, irredeemable bigots.

This indictment is extremely insincere, since the film spends the first half of the film lambasting the Polish for being unfairly vitriolic towards Jews. The second half then proceeds to contradict the first by reversing the roles, stripping its cautionary tone, and being ignorant of the subsequent hypocrisy.

In various scenes, the kids at the Kibbutz bully Tadek, using racial slurs, Polish jokes, and brash attempts at humiliation to make him feel like an outsider. The film’s original notion of racial tolerance is also sabotaged by the film’s constant presssure, via the children, to make Tadek change his identity from that of a Pole to that of a Jew (notice how Tadek, who remains Christian, has to hide his worhsipping). How can the film be so partisan while trying to be universal?

Take this conversation between Tadek and his brother as an example.

Tadek: “In general, they’re good people here”

Andrzej: “Good people? You know how they hate Poles?”

Tadek: “I know; they talk very badly of Poles. I’m afraid they’ll find out we’re not Jews. That will be the end”

Despite all this, Tadek inexplicably goes to incredible lengths to try and ingratiate himself with people that have clearly mistreated him, making everything feel incredibly manufactured and fake.

The ending and resolution of the film’s conflict is superficial and contrived, but by that point, none of it even matters, because My Australia’s real conflict is with itself.

– Justin Li

Visit the official website for the TJFF