El Gusto

Written and directed by Safinez Bousbia

Ireland, Algeria, UAE, France, 2011

Le voyage de Nadia

Written and directed by Carmen Garcia and Nadia Zouaoui

Canada, Algeria, 2006

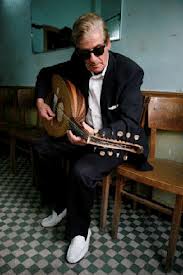

Recently screened at the Birds Eye Film Festival (a London festival dedicated to showcasing films by female screenwriters and directors), El Gusto, Safinez Bousbia’s first work in film sounds like a miracle by its sheer existence- a chance encounter in an antiques shop in Algiers’ Casbah inspired Bousbia to trace the destinies of the musicians who used to make up one of Algiers’ pre-independence chaâbi music orchestras, learning film-making in the process, going bankrupt, getting cancer, getting more funding, completing the film in 8 years, and undertaking a sold-out tour with the reunited orchestra, now in their 80s and 90s.

[vsw id=”y9t9YCcX3HM” source=”youtube” width=”640″ height=”375″ autoplay=”no”]

While it is hard to say that El Gusto is any way an out-of-the-ordinary or innovative documentary – there are very few gimmicks, the script is straightforward and free from rhetorical flourishes – the film, winding its way through the serpentine streets of the faded but buoyant Casbah of Algiers, captivates its audience through the heartfelt sincerity of the love for chaâbi music that seems to be the mainstay in the lives of the diverse cast of characters it follows. What the film lacks in stylistic sophistication, it makes up for by the layers of historical and geo-political complexity that are gradually peeled off as the narrative evolves from a music history documentary into an incidental exploration of the deep scars left in Algerian society as late as 50 years after the war of independence. Historical trauma traverses the stories of El Gusto’s characters in multiple ways – one can have a pick between the torture endured by former FLN associates, the lowly socio-economic status of musicians in Algeria, the dispersal of the orchestra members following independence, the prohibition of alcohol and closing of music venues, the semi-forced exile of the Jewish members of the band and the unquenchable nostalgia that life in France hardly ever began to obliterate.

Some of the most touching episodes involve the elderly French exiles’ reminiscences of a place and a time that will never return but will never leave them either, the longing manifest in the sensuality with which they savour their disused Berber-Arabic vocabulary, the painstaking removal of the entire interior of Algiers’ main synagogue from the scintillant cerulean of the Mediterranean to the gray-scale of Paris. Capturing of the essence of nostalgia – the suspension between irretrievability and irremediability – is what the film does flawlessly. Archival footage is used sparingly and judiciously in the sequences dealing with the civil war, with the author preferring to foreground the universal love of the music rather than attempting an overtly political commentary. The musical sequences are also finely balanced – improvisation and informality preferred to staged orchestration.

Some of the most touching episodes involve the elderly French exiles’ reminiscences of a place and a time that will never return but will never leave them either, the longing manifest in the sensuality with which they savour their disused Berber-Arabic vocabulary, the painstaking removal of the entire interior of Algiers’ main synagogue from the scintillant cerulean of the Mediterranean to the gray-scale of Paris. Capturing of the essence of nostalgia – the suspension between irretrievability and irremediability – is what the film does flawlessly. Archival footage is used sparingly and judiciously in the sequences dealing with the civil war, with the author preferring to foreground the universal love of the music rather than attempting an overtly political commentary. The musical sequences are also finely balanced – improvisation and informality preferred to staged orchestration.

Multiple geopolitical odds notwithstanding, El Gusto’s story has a bitter-sweet, almost salving ending – in one of the most soulful scenes, the French part of the band is waiting 50 years later at the port of Marseille for their Algerian mates as if it was just yesterday that they last played together, almost negating the passage of time. Not only were the surviving members of the original orchestra reunited, but they went on to earn belated recognition and success touring in venues in France and releasing an album.

Much as El Gusto is striking for the blatant absence of women in the life of chaâbi music, Le Voyage de Nadia makes up in its central preoccupation with the problematic customs of female domestic enclosure in rural Kabylie.

[vsw id=”rlXtP3y4quA” source=”youtube” width=”640″ height=”375″ autoplay=”no”]

The central figure, Nadia Zouaoui, similarly to Bousbia is an Algerian expatriate returning to her native land after years spent in the ‘west’ with the altered vantage point this implies. More intimate and just as heartfelt as El Gusto, Le Voyage de Nadia departs from personal trauma – an very unhappy arranged marriage in Canada – into an exploration of the Kabylian mores that perpetuate this commonplace fate. Interviewing women and men in her hometown of Takerboust, Zouaoui aims at shedding light at the two sides of a sad reality, that of married women who are forbidden by their family to leave the bounds of their family home.

Starting with her own mother, the author goes back in time interviewing elderly relatives sketching the source of this custom, then takes a look at the next generation’s inculcation into the institutionalised male domination of basic female activities (venturing out for groceries or taking an ill child to the hospital is considered unbecoming of female modesty). Interestingly and encouragingly, the majority of female interviewees and some of the male ones are cognizant of the absurdity and injustice of these age-old restrictions – from the outcast relative who prefers divorce and banishment on a rooftop to sharing her husband with another wife to the elderly woman who sardonically proclaims that the happiest years of her life were when her husband was away working in France to the liberal (quasi-butch) veterinarian who is sceptical of her chances of finding an accommodating husband, each struggle resonates with the author’s own traumatic history (she refers to her wedding night as ‘rape’).

To the filmmakers’ credit, Zouaoui’s narration achieves the feat of being simultaneously lucidly critical and lovingly respectful of the culture and traditions of her homeland. The portrait of this society characterised by patriarchal extremes devoted to the glorification of family honour is nuanced by the introduction of external politically motivated factors (the rise of Islamic fundamentalism versus the historically moderate Berber religious identity) and while never oblivious of the daily injustice perpetrated towards females, the journey of the title is sincere in its quest towards understanding the causes rather than merely offering a litany of the wounds.

Zornitsa Staneva