America has always possessed a winning mentality, and proudly boasts about it at any passing opportunity. Between politicians who claim the United States is the greatest country in the world – with no statistical data on hand to back such claims, no less – and college frat boys wearing tees or tank tops that read ‘Back to Back World Champs’ at social functions, to some the idea of America being second-best in any respect is sacrilegious. It’s bits of history like the Vietnam War that these folks would rather brush to the side for the sake of argument. For many, the failure of Vietnam was a “sackcloth of humiliation,” and for once the country found itself in the role of victim rather than victor. Even worse, it was broadcast for everyone to see; front-row seats to the impotence of American intervention.

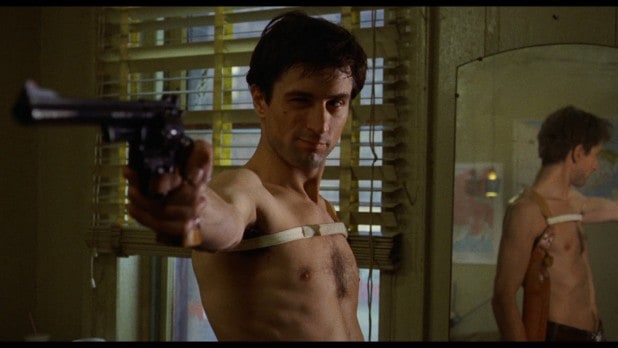

Less than a year after the end of the Vietnam War, Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver was released on February 8th, 1976. Written by Paul Schrader, the film is a psychological character study of Robert De Niro’s Travis Bickle, a Vietnam vet who takes a job as a night shift cabbie. His late hours expose him to what he considers the scum of the earth, and his progressively deteriorating mental state leads him to a complete break and disillusionment with reality. A personal project for Scorsese, De Niro and especially Schrader, none of the three believed that the film would prove successful; in fact, Scorsese has admitted that their motivation for making it was simply because they had to. Well, of course, Taxi Driver wound up being one of the best films of the year; it was nominated for four Academy Awards, including Best Picture, and won the Palme d’Or in Cannes three months after its American premiere.

Taxi Driver was a big success with the public, as well. With a production budget totaling $1.3 million, the filmed scored a little over $28.2 million at the box office. Clearly Travis Bickle’s story of self-imposed loneliness and desperation to belong somewhere struck a chord with many people – even unfortunately so with John Hinckley, Jr. – and has continued to do so, making it one of the most culturally impactful films of all time. What is it, however, that drives Travis’s inability to fit in his surroundings? There are numerous scenes where Travis seems out of touch with societal realities, and they continue to feed into his modes of thought that rationalize overtly violent reactions. Yes, Travis becomes increasingly alienated from society as the story wears on, but what he is being alienated from is a Post-Vietnam America still trying to recover from defeat.

Martin Scorsese is a very urban director; no matter the highly populous milieu, he understands its people, its movements and its flow. Being born in New York, there’s no other setting that he understands more fully, which he had previously depicted in Who’s That Knocking at My Door (1967) and Mean Streets (1973), which was his first working experience with De Niro. There’s something peculiar, however, about how Scorsese depicts the Big Apple in Taxi Driver. Taxi Driver is an overtly urban film, but the only aesthetics that let you know the setting is New York are the addresses characters refer to. Aside from a quick shot of Times Square in the hallucinatory opening credits sequence and perhaps the presence of the yellow taxi – present in many cities, yet an iconic, singular symbol of New York – Scorsese merely gives us an outline of the city. As a result, one of America’s most recognizable cities appears completely homogenous; New York’s struggles become the struggles of cities across the country.

Post-Vietnam, the city is a shell of its former self, and given the combination of Schrader’s writing and Scorsese’s direction, Taxi Driver implicitly tells us that the city and America itself are experiencing a bit of an identity crisis. When we’re first introduced to Albert Brooks’ character Tom in the New York headquarters for Charles Palantine’s presidential campaign, he’s arguing with someone about campaign buttons that say “We Are the People,” rather than the campaign’s real slogan “We Are the People.” He argues that the two have different meanings, and he’s right. Like the mistaken slogan, “We Are the People” is a bold exclamation, but its ‘We’ is much less concrete than the former. Is the real ‘We’ inclusive or exclusive? The audience doesn’t know, and neither do they, as their identity – and on grander scale, our identity – isn’t fully realized.

This is the world that Travis Bickle’s taxi confines him to every night, and the ‘scum’ he’s subjected to every shift further adds to his disillusionment with the state of Post-Vietnam America. Even in a country still reeling from defeat under the surface, Travis never quite fits in ideologically with his peers, those on the streets and those in the political spectrum. His views on the “animals” that come out at night and how a “real rain” needs to come wash the streets clean further alienate him from his surroundings; they affirm his self-proclaimed status as “God’s lonely man.”

There’s only one circumstance where Travis can comfortably be himself, and that’s when he’s around Iris (Jodie Foster), the pre-teen runaway turned big-city prostitute for manipulative pimp Sport (Harvey Keitel). With Iris, he tries to usurp the perverted father figure role filled by Sport, and to do so would be well within the bounds of his outdated patriarchal ideas of male obligations, which miserably failed with Betsy earlier in the film. In fact, his ideals match those of a hero in a John Wayne western, and he acts in his environment in such a manner.

In Sophie Fiennes’ documentary The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology, psychoanalyst and cultural critic Slavoj Žižek refers to Taxi Driver as an implicit remake of John Ford’s The Searchers. Both films contain female characters who are “perceived as [victims] of brutal abuse.” But like how John Wayne perceives Natalie Wood in Ford’s film, Žižek hypothesizes that Travis sees Iris as someone who enjoys and actively participates in her victimhood, thereby justifying his internal desire to save her and the violence he commits at the film’s end. But really, in a post-Vietnam landscape, Travis sees the city as participating and actively choosing not to fix its newfound victimhood, as well. Not only is his bloody shootout a darkly justifiable means of saving Iris, it’s an ultimately shortsighted means to save the city. But how exactly did Travis go from despising the city’s underbelly to believing the city needed to be saved from it?

To understand the sort of person Travis is before his eventual break is to understand the importance of taxi drivers, in general. The 2007 Collector’s Edition release of Taxi Driver includes stories from a handful of men who were New York City taxi drivers during the 1970s and experienced similar things as Travis. These men are commonly known as the great ambassadors of the city, and they communicated the importance of being personable and conversing with riders. They also confessed how easy one can get trapped in the job, and the stronger Travis’ own ideology becomes, the more he’s fenced into this narrow, singular view of the city where he is physically and personally separated from the rest of society.

We first meet Travis applying to become a taxi driver, as he’s looking for long hours. His flannel shirt and baggy Marines jacket conceal his slight frame as he stands before the man in charge. He seems a quiet fellow at first, but then he makes a little wisecrack about how his driving record is “clean, real clean, like [his] conscience.” He desires a sense of camaraderie he would have had in Vietnam, and which he can see Wizard and Doughboy sharing through the window behind the desk. The man behind the desk doesn’t take to kindly to Travis’s sense of humor, and the camera rises from a medium shot of Travis to a close-up of his face as he apologizes with a mysterious smirk left on his complexion. The two bond over both being in the Marines – Travis says he was honorably discharged in May ’73 – but because of that aforementioned shot, you get the sense that Travis’s perceived affront lingers with him.

While he seeks that sort of friendship with his taxi-driving peers, it’s never to be found. Fellow cabbies Wizard, Doughboy and Charlie T gather nightly at the Belmore Cafeteria while they’re off, and during their down time the group listens to Wizard recounting such stories of sharply-dressed little people and quarreling homosexual men riding in his cab. The group enjoys his stories, but their reactions suggest that they’re rather normative, either for Wizard himself or even given their own experiences as taxi drivers. As soon as Travis enters the space, the tone of the conversation changes and he’s never able to enjoy in the stories Wizard tells with the rest of the gang until the end of the film. While he isn’t very successful in cultivating any friendships, he nearly finds some success with romance.

Travis was enamored with Betsy from the first moment he saw her, saying that she “appeared like an angel out of this filthy mass” in her white dress. He believes that she experiences the same loneliness as he, and in his mind that justifies creepily staring at her from his cab and then boldly asking her out. The patriarchal expectations of how men conduct themselves when initiating a romantic relationship work at first, until the second date when he takes Betsy out to a foreign adult film. Betsy is reasonably disgusted by what she sees and storms out.

Working at a presidential candidate’s office, Betsy feels like the embodiment of Second Wave feminism. She’s strong-willed, demonstrates her equality in the workplace and is the absolute opposite of the women Travis’s routine might work on, which is potentially why Travis feels some satisfaction in being Iris’s guardian angel. In the moment, he’s content in believing that she’s “in a hell” and “just like the rest of them,” which is both a dig against what he identifies as scum and the feminist movement. In fact, to generalize the feelings of women, he refers to them as “cold” and “like a union.” Later that night, a peculiar customer would unwittingly complete his transformation into complete ideological madness.

At this point, Travis is nearing the end of his rope. Then he picks up a man who instructs him to park his car by the curb outside the apartment where he suspects his wife is making love to another man. He then tells Travis about his plans to kill both of them, but when he asks Travis if these plans of his disturb him, Travis’s reaction is mute. The camera pans from the disturbed rider to Travis, then cuts to the back of Travis’s head, as if we’re not allowed to see his genuine reaction, although getting the feeling that he finds nothing wrong with his customer’s sick fantasies.

In The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology, Žižek proclaims, “Fantasies are the central stuff our ideologies are made of.” In this moment, the fantasies of the cab rider bring to life the hidden fantasies that Travis had managed to repress. Žižek claims that from a psychoanalytic perspective, fantasies are “fundamentally a lie,” not because they are the opposite of reality, but because they “cover up a certain gap in consistency. When we cannot get to know things, fantasy provides an easy answer.” Sitting in that cab, completely trapped inside of his strengthening ideology, Travis cannot know the people he uses the blanket term ‘animals’ for, therefore after meeting this cab rider, the only logical step for him is a suicidal burst of violence, which is given direction by Iris’s victimhood.

It would be moot point to say that Taxi Driver is a landmark of 1970s American cinema. The “You talkin’ to me?” monologue has been oft mimicked in other sections of pop culture, and Travis holding his bloody hand in the shape of a pistol to his temple and mimicking pulling the trigger is arguably one of the most iconic images in film. If Mean Streets introduced American audiences to Martin Scorsese, then Taxi Driver firmly cemented his rising status as one of the great American directors. And in spite of his strongly held beliefs, Travis Bickle remains one of the great American characters.