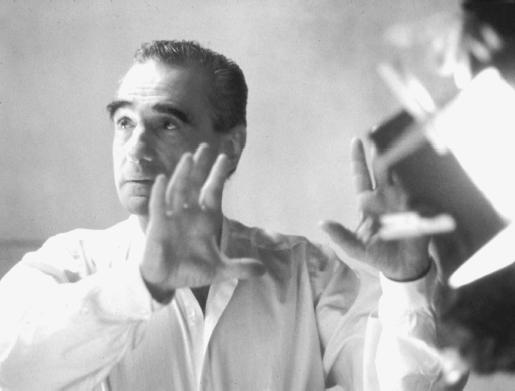

In an ideal world, every filmmaker would live long enough to see the premiere of their final film, even if their life is ended sooner than expected. It’s one thing to experience shooting the film and editing the final product, but it is another thing entirely to witness your creation with an audience seeing it for the first time. Pier Paolo Pasolini is one such director who never witnessed his final film in the company of an audience. 20 days before the premiere of Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom at the 1975 Paris Film Festival, an unknown assailant, or group of assailants, murdered Pasolini. A well-known provocateur in film and the political arena, Pasolini unknowingly saved his most controversial work for last.

Salò is a notorious adaptation of the Marquis de Sade’s equally infamous novel The 120 Days of Sodom. In Pasolini’s film, however, the novel’s four wealthy, 18th century French libertines become four wealthy Italian fascists looking for ways to keep their power after Benito Mussolini’s nearly 21-year long reign as Italian Prime Minister came to an end. Also inspired by Dante’s Divine Comedy and marginally referencing works from Friedrich Nietzsche, Ezra Pound, and Marcel Proust, the film keeps all of the Marquis de Sade’s literary acts of sexual degradation, perversion and torture intact.

I certainly needn’t explain everything that happens in the film, because those of you reading have either already seen the horrors within or, at the very least, know about them. And for those you who haven’t seen this picture and have no knowledge of why this film remains controversial, perhaps it is best to just let you experience the film for yourself with blind eyes. What I can tell you all, especially for you Salò virgins, is that Pasolini does not once compromise beauty and cinematic poetry for the sake of sheer brutality, something that maybe today’s horror filmmakers could learn from.

My first experience with the film was without any subtitles, and I thought that my lacking any knowledge of Italian would prove a complete hindrance. While it would have been nice to know all of the dialogue spoken, there is plenty of context and emotion that doesn’t get lost in translation. The film begins with an easygoing string and horn ensemble reminiscent of something you might have found in a nightclub during the 1940s, followed by beautiful scenes of Salò, a small town located in northern Italy. It is the first- and definitely not the last- time Pasolini lulls the audience into a sense of disquiet. The rest of the nearly two-and-a-half hours is filled with calm and steady camerawork that completely belies the deviant and disturbing activities it depicts.

Consistently cited as one of the most disturbing films ever made, Pasolini’s final film is equally revered and reviled. One thing about films such as Pasolini’s, those with an intention to shock and disturb through graphic depictions of inhumane acts of barbarism, is that the level at which they achieve their goals does not fade over time. Salò is as grimly effective as it was 40 years ago, and while it might not be fair to stick Pasolini’s film in the same class as I Spit on Your Grave and Cannibal Holocaust, both of those films have similarly lasted throughout the decades thanks to cult followings. In a very perverse way, these films are timeless, forever destined to test the limits of what can be shown on film and those who don’t consider themselves squeamish.

Many of these films were loaded with style and substance that kept them from being disturbing for purely that sake. Whether an art film or a grindhouse shocker, many of these films, including Salò, deeply focused on psychological, sociopolitical and cultural themes, proving intelligence behind the madness. While these films stood out as individual efforts rather than part of a comprehensive era in cinema defined by violently divisive filmmaking, they have left a legacy that lives on in contemporary drama and horror filmmaking. If you don’t count Wes Craven’s The Last House on the Left – or even Ingmar Bergman’s The Virgin Spring, the basis for Craven’s debut – then Pasolini’s Salò is at the forefront of creating that legacy. Where we were a few years ago, however, was a fortunately brief era of less intelligent films more concerned with upping the ante rather than pushing boundaries and living up to that legacy.

The 70s was arguably the first era of truly global experimentation in film. From an American perspective, with the downfall of the Hays Code in the late 60s, filmmakers were given free license to graphically depict violence and present other subject matter censors would have found immoral and potentially damaging to the public. Internationally, graphic violence was acceptable, but only to a point depending on each nation and their censors. The depictions of violence became more graphic as years passed, highlighting another reason why films like Salò were so important. In addition to plunging into the themes listed above, these films redefined what the boundaries were in an age when graphic violence in film was relatively new, so exploration was necessary.

Today it’s fair to say that these boundaries no longer exist, and modern filmmakers have exploited this recent luxury for the sake of deranged entertainment rather than art. With the advent of films like High Tension and Saw, we saw a rise of two separate movements in film in the early to mid 2000s: torture porn and the New French Extremity movement. These movements encompassed films that reveled in disturbing amounts of graphic violence and torture, and most of them existed for that very purpose.

Between the Hostel and Saw series, the further these franchises progressed, the less they became focused on plot and the more they were trying to devise new ways to brutalize their victims for the audience’s viewing pleasure. By the time the final Saw film premiered in 2010, however, the torture porn revolution in the U.S. had all but limped its way out of mainstream consciousness. Without a new film every Halloween season to get people to come to the theater, the craze has all but dissipated into the realm of straight-to-DVD horror that only the most hardcore of horror junkies would actively seek out.

New French Extremity, however, is a bit of a different beast. On the one hand, you have films like Gaspar Noe’s Irreversible (although it’s involvement in the movement is up for debate), Pascal Laugier’s Martyrs and, to a certain extent, Xavier Lens’s Frontiers. These films are incredibly unrelenting in their attempts to make viewers squirm, but they feature plenty of substance giving the violence purpose. And then on the other hand, you have films like Inside. It, and to large extent Frontiers, only seem intent on painting the walls with bloody viscera, ensuring the film is red from first frame to last. Frontiers features more explicit torture, but Inside features a series of bone-chilling mutilations that don’t amount to easy viewing. Like torture porn from the States, the popularity of New French Extremity among horror fans began to decline at the beginning of the new decade.

Pasolini never could have imagined that either of these temporary cinematic trends would briefly present themselves as the future of film. These films are completely unapologetic about their identity, and while not everyone embraces these pictures, thanks to a movie like A Serbian Film, we can appreciate that those films and their filmmakers acted with a sense of moral boundaries, and had the decency to be upfront with their audience about their intentions. Seriously, the filmmakers of A Serbian Film couldn’t be bothered to tell their first audience in Austin their intentions until a post-screening Q&A session.

This is the unintentional legacy that Pasolini’s Salò helped create. After the virtual disappearance of torture porn and New French Extremity, it seems unlikely that there’ll be any similar cinema craze any time soon. The only certainty is that some twisted nut will try and outdo what A Serbian Film accomplished. Nowadays, the creation of films like these is nothing more than a glorified pissing contest. There’s always one asshole who thinks they can go the farthest.