Let Me In

Let Me In

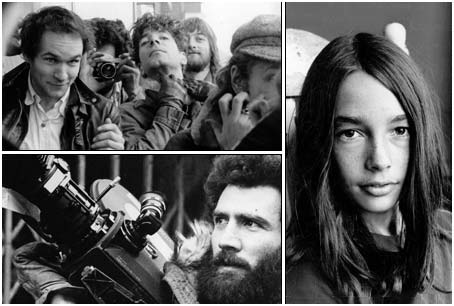

Directed by Matt Reeves

vs.

Let The Right One In

Directed by Tomas Alfredson

Even in a pop culture landscape littered with the bloodthirsty undead, Let The Right One In stood out as a poignant coming of age story as well as a bone-chilling horror film. The haunting mediation on the difficult and often painful transition into adolescence garnered much praise on the festival circuit in 2008. The film earned a loyal cult following through word of mouth and when Matt Reeves announced his American remake, those very same cinephiles lashed out in anger. The general consensus was, “why fix something that isn’t broken?”

Sadly, mainstream audiences seem to have a problem with subtitles, so it was inevitable that the film would be remade. That said, fans of the original should  be grateful that Matt Reeves (Cloverfield), alongside legendary British horror brand Hammer Films (a studio that set a new tone for the vampire lore) got the job done, because Let Me In is an almost flawless film.

be grateful that Matt Reeves (Cloverfield), alongside legendary British horror brand Hammer Films (a studio that set a new tone for the vampire lore) got the job done, because Let Me In is an almost flawless film.

Based on the best-selling Swedish novel “Let The Right One In” by John Ajvide Lindqvist, and the highly-acclaimed film of the same name, Let Me In is a haunting, provocative thriller and in many ways is better than the original.

While originally pegged as their own vision of the novella, it’s clear that director Matt Reeves has mimicked Alfredson’s distinctive sense of style and looked to his adaptation for visual inspiration. Reeves takes a bold and critical step in shooting an almost shot-for-shot remake of the Swedish vampire flick. But by injecting his own craft, he finds a way to harden it with a little more emotion and flavor.

It’s clear from the start that another way Reeves differentiates his adaptation from the Swedish one is that Let Me In is actually frightening. Reeves opens midway through the story, quickly establishing the uneasy, foreboding tone as an ambulance transporting a victim of a brutal car accident wends its way through the dark, stormy and winter terrain. It’s a gripping, unsettling and truly horrific opening in which Reeves demonstrates an adept sense of how to generate dread and suspense through clever camera work, brisk framing and suggestion. While many of the memorable set pieces from Alfredson’s film are recreated with precision (discovering the body under ice, gutting a victim in the woods, and the unforgettable pool scene), Reeves tweaks a few scenes by adding a bit more blood loss and superb prosthetics. In addition, he stages an entirely new, bravura car crash sequence and some unique p.o.v. shots that showcase better camera work than that of the original. Reeves also makes a conscious decision to strip away any glimpses of Owen’s mom and dad, reducing his parents to out of focus background figures or distant voices.

Let me In transports the snowbound 1990’s Swedish setting of the original to a small town in 1980’s Los Alamos, New Mexico. We’re in a bleak American landscape when the Cold War was still at its  height and Ronald Reagan is seen on a television set giving his “Evil Empire” speech. Later on, after watching Abby attack a woman, Oscar makes a phone call to his absentee father, asking his dad, “Do you think there’s such thing as evil?” It’s an interesting tie-in, showing how it would be like for a 12 year old boy harboring dark feelings deep inside to grow up in that context.

height and Ronald Reagan is seen on a television set giving his “Evil Empire” speech. Later on, after watching Abby attack a woman, Oscar makes a phone call to his absentee father, asking his dad, “Do you think there’s such thing as evil?” It’s an interesting tie-in, showing how it would be like for a 12 year old boy harboring dark feelings deep inside to grow up in that context.

Grieg Fraser’s (Bright Star) cinematography is breathtaking, turning Los Alamos, New Mexico into a ghost town, a place cut off by a perpetual chill, and he sets Owen adrift in it. Tonally, the Swedish and American versions are the same especially when sculpting light and shadow, only Fraser at times opts for a brighter warmer colour palette when the two young leads are left alone. Blue becomes orange, and the winter cool feels early autumn. The contrast carefully compliements their relationship both with each other and the outside world without ever overpowering the story.

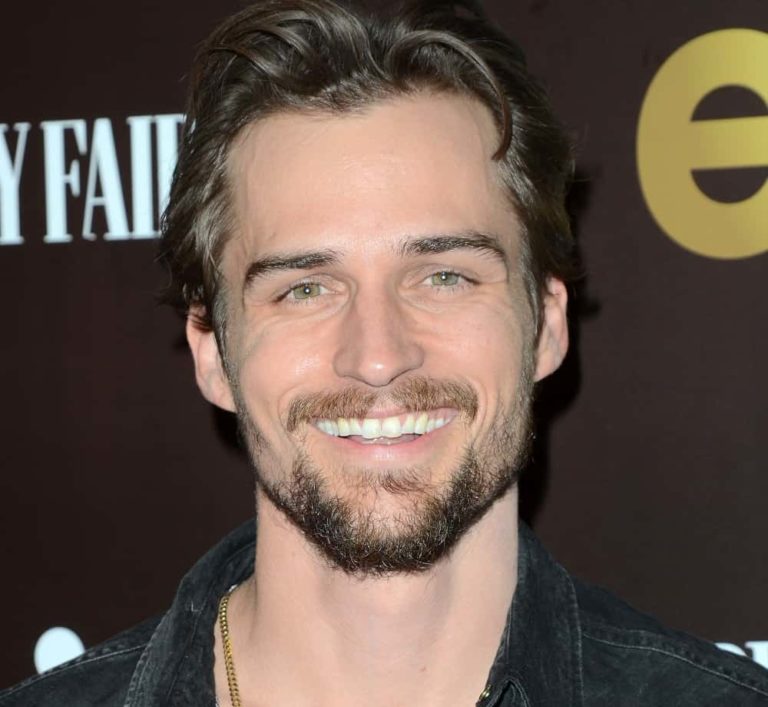

With the emotional resonances of the film resting on the narrow shoulders of its preteen protagonists, the filmmakers knew the chemistry between Abby and Owen was crucial. Credit to Avy Kaufman, the film’s casting director, who’s known for discovering a number of extraordinary child actors including Haley Joel Osment in The Sixth Sense, Max Pomeranc in Searching For Bobby Fischer and Adam Hahn-Bird in Little Man Tate. Chloe Moretz delivers a breakthrough performance; to the naked eye Abby appears to be caring and loving of Owen, but under further investigating she’s actually quite sinister and devious. Moretz is a remarkable, intuitive actress who is able to project a presence far beyond her years. Her consistently enthralling turn as Abby undoubtedly matches (maybe exceeds) Lina Leandersson’s stellar performance in Alfredson’s 2008 original, while her more sympathetic presence makes this a more emotionally satisfying film to a certain extent. While there isn’t a lot of dialogue, Reeves finds clever ways to drive the innate soulless of his characters with skillful direction particularly in Kodi-McPhee’s stellar performance as Owen. A prime example of how Reeves dabbles in Owen’s breaking psyche is in a scene in which Owen, wearing a disfigured mask repeatedly stabs a mirror screaming. These small but important changes showcase Owen’s anger, fear, loneliness, frustration and dark side. While Kåre Hedebrant (Owen’s equivalent in the original) has a slight edge in performance, Kodi’s unique goth look – jet black hair, long eyelashes, Morrisey like haircut, dressed in Khakis and Izod sweaters looks more the outsider.

Richard Jenkins, whose melancholic demeanor is put to good use as Moretz’s doomed caretaker equals that of Swedish actor (Per Ragnar playing the same part) but it’s Elias Koteas, in the added role of a police officer, that makes the biggest difference. Koteas, a seasoned character actor with an enviable resume both in film and TV, plays the nameless detective, trying to piece together the mysterious murders taking place in the small town. Koteas is another one of those guys who just plain does great work consistently, and here he makes for a credible moral compass while attempting to uncover the truth.

a police officer, that makes the biggest difference. Koteas, a seasoned character actor with an enviable resume both in film and TV, plays the nameless detective, trying to piece together the mysterious murders taking place in the small town. Koteas is another one of those guys who just plain does great work consistently, and here he makes for a credible moral compass while attempting to uncover the truth.

Finally echoing the prevailing, mournful tone is Michael Giacchino’s exquisite score, which is achingly poignant and far superior to that of the original Swedish film. Giacchino (who also contributed a piece of music to Cloverfield) sets the tenuous emotional tone of the film using a bell-like keyboard instrument called a celese as well as bass drum and a boy’s choir. His score is spare, haunting, rough at times and reminiscent of some of Jerry Goldsmith’s best work.

The pressure in adapting a story or remaking a film is that the filmmakers already have an archetype to which everyone will compare their work to. Some people will be unwilling to invite this film in, but those who do, will be rewarded. Let Me In is a film that achieves the rare feat of remaining faithful to its source material while emerging as a highly accomplished work in its own right.

Despite my statements above, it’s hard to argue Let Me In is a better film when considering Reeves was evidently influenced by Alfredson’s version. That said, Let Me In is every bit as valid a take on Lindqvist’s novel as the film by Tomas Alfredson was. Purists may be outraged by these statements, but Matt Reeves approached this material with a keen eye and a sharp wit. Unlike every other remake, Reeves clearly isn’t a director for hire. This isn’t a project started to make a buck. Reeves’s passion and love for both filmmaking and the original source material comes through in every frame. Let Me In is a spectacularly moving and elegant movie, and to dismiss it as just a remake, is to overlook a remarkable film (even if it is missing the famous scene involving the cat).

Ricky D