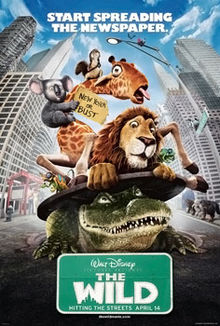

The Wild

Directed by Steve ‘Spaz’ Williams

Written by Ed Decter, John J. Strauss, Mark Gibson, and Philip Halprin

Starring Kiefer Sutherland, James Belushi, William Shatner

Every movie, every television show, every book, every play, and every musical needs to have internal logic inherent in its creation. No matter how ridiculous the premise is—a man dresses as a bat to fight crime, a high-school teacher resorts to cooking methamphetamines to make money, and so on—there must be logic present. If there isn’t, the story falls apart as soon as you think about it. The real trick that some filmmakers or other creative types can employ is not making you think about the story while you’re experiencing it. As an example, while I loved Mission: Impossible – Ghost Protocol, and can’t wait to watch it over and over on Blu-ray, does it hold up to intense scrutiny? Probably not, but in the moment, I’m caught up in the action, not picking it apart.

I may sound like I nitpick things on the podcast, but we all do this. The difference is how often we are struck by what we nitpick. Even a person who goes into watching movies with a critical eye—which I find myself doing more often for the show than when I watch non-Disney movies—can get pure enjoyment out of what they review. The difference is if the people behind the camera can actually immerse us in the story they’re telling, or if I’m too busy picking apart the entire production. Something that I often come back to, something I don’t explicitly demand of a movie but I expect each movie to have, is internal logic. Even if the movie you’re making, such as The Wild, is about animals who talk to each other, you need to have internal logic.

So why, you may ask, do movies not always have internal logic? Or, why do we sometimes find ourselves disagreeing with the logic of a movie? Why do we say, “Character X wouldn’t say that. Character Y wouldn’t hit Character X,” or something like that? Sometimes, it’s a case of an audience being on a different track than the creator; the creator may think Character X would say that, but we may not, based on past interactions, agree. Sometimes, though, the problem isn’t that whoever wrote a movie has a different vision of the characters and story than we do. Sometimes, the problem is that the audience is putting more thought into a movie’s internal logic than its creators have. And that is, I think, the essential problem with The Wild, a 2006 computer-animated film distributed by Walt Disney Pictures but created by C.O.R.E. Digital Pictures, an animation company that also created Valiant and The Ant Bully, also known as two movies that most people don’t have memories of, let alone fond ones.

The Wild takes place in the present day, opening at the New York Zoo, where Samson reigns as the star attraction of the zoo, an African lion. He’s a little let down that his son, Ryan, doesn’t have any oomph to his roar, which makes his son feel so guilty and frustrated that, after a fractious argument, he says he wishes Samson wasn’t his father. And then he inadvertently gets taken away in a Rescue container headed for the jungle. Samson, with some fellow zoo inhabitants, heads to the eponymous wild to save his son and bring peace to their relationship. If you read that synopsis, or heard us on the podcast, you may think this sounds like a weird hybrid of Finding Nemo and Madagascar, weird in that it doesn’t seem to hide its influences at all. And you’d be right.

You may argue that most movies these days aren’t original, that they’re all based on other stories or characters or general archetypes. And you’d be right. But what matters isn’t that The Wild is unoriginal. What matters is that you can spot from that synopsis how unoriginal it is. If you can tell a new variation on an old story, that will matter more than your inspiration being an old story. There is no special variation present in The Wild, which has the distinct and unpleasant feeling of just being made for the money. Creativity can flourish in a corporate environment, as evidenced by the partnership between the Walt Disney Company and Pixar Animation Studios. The latter could create simple, easy, cheap movies that make money, but the people at Pixar pour their hearts and souls into what we see in theaters each year. I cannot make the blanket assumption that the people who made The Wild didn’t have the same passion, but the passion was not evident.

Am I being unfair in comparing this film to the work that Pixar has done for the last 17 years? Maybe, but I think it’s inevitable. There are very few computer-animated movies released in the United States that aren’t from either Pixar or DreamWorks Animation. When a smaller animation company cribs heavily from two notably popular films, one from each of those bigger companies, it’s as if they’re asking to be compared. Inviting the comparison to Pixar is awfully dangerous, as it can sometimes be for Pixar’s own movies. (See, for example, the Cars films, which are flawlessly animated and have weak and dull storylines and characters.) Even worse, the people at C.O.R.E. have, it seems, a rough idea not only of how to build story and character, but to animate.

I hesitate to decry the animation in The Wild, because presumably hundreds of men and women worked on the film for years. And yes, C.O.R.E. isn’t Pixar or DreamWorks. They don’t have the same amount of money. (Unfortunately, the company has been defunct for a couple of years.) And maybe if I was watching this movie, not knowing it came from Walt Disney Pictures, I wouldn’t have as much of a problem with the incredibly cheap-looking, sometimes disquieting character animation. While Disney animators didn’t actually put pen to paper—or mouse to computer—for the film, this is a Disney movie. So I have to judge it based partly on how other Disney movies look. Even if we take away the many hand-drawn animated movies from Disney’s animation arm, we’re left with such films as Bolt and Tangled. Story-based quality aside, those movies have better, less distracting animation. Though this movie’s animation never is so realistic that it has an “uncanny valley” effect—wherein the animation is almost too realistic, to the point of being uncomfortable to look at—it’s frequently disquieting to look at because…lions don’t look like that.

I’m not saying I wanted photorealistic lions from the animation in this movie. Even Pixar films don’t create photorealistic animals—Dug from Up looks both like a dog and like a caricature without being distracting. But the lions, especially, look distracting, not appealing. From the get-go, I was struck by how low-rent the animation looked. I was even more gobsmacked when I looked at the film’s budget. On the one hand, you may argue that any movie featuring the voice talents—and I use the word “talent” very loosely here—of Kiefer Sutherland, Eddie Izzard, William Shatner, and Jim Belushi isn’t going to be incredibly cheap. Still, none of the actors here are movie-star-level popular. So reading that The Wild cost roughly $80 million is a bit of an eyebrow-raising moment. How much money was actually spent on animation? The answer is, not nearly enough.

There’s something soulless not just about the animation in the film, but the whole story. One issue that often comes up with recent animated fare is voice performances. Though most people don’t realize it, plenty of actors work specifically in the recording booth these days, relying on animation to pay the bills. Many of these hardworking folks are somewhat (and rightfully) resentful of studios hiring big-name actors to lend their voices to animated movies, on the presumption that people will flock to those movies simply for those actors being involved. Sometimes, movie stars have the right voice for animated work; could anyone but Tom Hanks, arguably one of the biggest movie stars in the world, be the voice of Woody from the Toy Story trilogy? But for every Hanks, there’s a host of actors, from Angelina Jolie to Robert De Niro, who just don’t have distinctive enough voices to work in animation. The connection between character and actor can either be inextricably linked or as distant as possible.

And that’s the case in The Wild, specifically with Sutherland, as Samson. I’m actually a big fan of Sutherland, whose recent stardom is thanks to his Emmy-winning work as Jack Bauer on the departed action series 24. Playing an extremely determined father willing to do anything to get his son back sounds like it’s right in his wheelhouse. But there’s never a point in this movie where Sutherland doesn’t sound like he’s dubbing over someone else’s performance. I never had any connection to the characters or the story. I don’t blame Sutherland for the fact that he’s mired in a derivative film, but his performance isn’t remarkable in any way.

Regarding the story being derivative, you may remember that my co-host Michael pointed out, rightly so, that whatever similarities this film may bear to Madagascar could potentially be ignored. The latter film opened in May of 2005 and the former opened in April of 2006. While there’s an 11-month gap between them, the two stories may have been competing without realizing it. Certainly, there were once a spate of strangely similar films—Volcano vs. Dante’s Peak, Armageddon vs. Deep Impact, and A Bug’s Life vs. Antz—but those examples prove the problem. Whatever criticism I may levy against either Antz or A Bug’s Life, for example, they are inherently different stories. Yes, both take place in a colony of ants. And yes, both are computer-animated comedies. But one is, in many ways, a romantic comedy and the other is a rousing adventure. Both are plenty formulaic, but the stories feel different.

The story worked for Michael, partly because he was engaged by the characters. I found no connection with these characters. I didn’t care about Samson getting Ryan back, because at every point in the film, I was never immersed in the world. By not being immersed in the world, I knew that of course Samson would get Ryan back because it’s a Disney movie, and what Disney movie would end with a downer ending? (What animated movie, for that matter.) Whatever attempts at cleverness were snuffed by either flat voice performances or dull characters, also. Half-baked attempts at building stories and worlds and characters aren’t, perhaps, as bad as a complete lack of such attempts, but The Wild represents, to me, nothing short of an 80-minute visual and aural definition of the word “dull.”