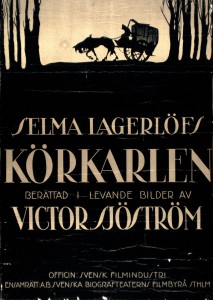

Directed by Victor Sjostrom

Written by Selma Lagerlof and Victor Sjostrom

Cinematography by Julius Jaenzon

For many, the tired face and defeated body of Victor Sjostrom became synonymous with mortality in Ingmar Bergman’s pivotal film, Wild Strawberries. Few know that he was not only Bergman’s mentor but one of cinema’s greatest filmmakers. For Bergman, there was no greater film than Sjostrom’s The Phantom Carriage and he would revisit it yearly, often on a summer day, losing himself in it’s angst and plays of light.

There are many similarities between Wild Strawberries and The Phantom Carriage. The most obvious being the central force of Sjostrom, who not only directs The Phantom Carriage but stars in it as well. Both are about men hardened by life, forced to confront and reflect upon their empty existence. Sjostrom plays a much younger man in his own film, but his life was no less hard or long than the ageing professor’s.

Both films rely heavily on the powers of the unconscious mind and the effortless movement between reality, dream and memory. At the centre of The Phantom Carriage is a supernatural force. A force between God and the Devil, a figure of death who exists more in the land of myth than on a spiritual plain. Sjostrom’s vision of the afterlife suggests the concept of heaven and hell, but never delves into it. This is a cruel world where faith means little in the face of chance. The premise of the film is a carriage of death that gathers the souls of the recently deceased. Each carriage driver has a one year term which is decided merely on a whim: the last soul to die in a given year must take the unfortunate carriage’s helm.

This suggests chaos, but there is an organization to the choosing of the man. It is not the good or hardworking who seem prone to this fate, but the rotten, and there is no man more rotten than David Holm (Victor Sjostrom). This is a man who is offered ample opportunity for redemption through love and forgiveness, but he decides to turn away from it again and again. He is not an evil man, but a man whose soul is darkened by hardship and sin.

Wild Strawberries draws on this spiritual landscape and refines it to suit Bergman’s developing style. In his previous film, The Seventh Seal, the presence of spiritual and moral conflict are externalized in a figure of death, much like The Phantom Carriage. However, in Wild Strawberries this landscape is defined through the subconscious of the characters. The magic of Sjostrom’s films though, comes from this relationship between the external supernatural forces and the internal workings of the soul.

The Seventh Seal, the presence of spiritual and moral conflict are externalized in a figure of death, much like The Phantom Carriage. However, in Wild Strawberries this landscape is defined through the subconscious of the characters. The magic of Sjostrom’s films though, comes from this relationship between the external supernatural forces and the internal workings of the soul.

Aesthetically, the film blends realism with the supernatural. The forces of nature hang around the edges, representing at once a natural ideal and an uncontrollable force. A tactile fantasy sequence is set in an idealized natural world where David Holm gets a glimpse into the life he could have lived had he not been a self-motivated drunkard. This contrasts with the crashing and frozen waves of the sea. The sea is unforgiving and no living being can escape it’s wrath, this is a place where only the Phantom Carriage can traverse.

Lighting becomes essential to the film’s mood and becomes a gateway to the subjective and supernatural forces. The lighting is often realistic and there is often a suggested light source within the scene. A frequent use of a wide iris envelops the characters in darkness. Superimposition is also used heavily to suggest the ghostly apparition of the carriage and the phantom world that co-exists unseen with the land of the living.

What makes the film feel surprisingly modern, though, is the performances. There are no histrionics on display and the acting techniques are suitably naturalistic. Amidst the various stylistic techniques, each sequence returns to the human element and the actor’s face. This restraint favours authentic emotions, and the film is less of a parable or melodrama  about evils of drinking or sin, then it is a story of a lost individual: It is about one man’s inner violence and search for redemption. The Phantom Carriage is not plagued by preachy morals and as a result there is no easy reading of the film’s uplifting conclusion. This ending is weighed down by the overbearing darkness that precedes it and does not feel like a strong consolation for this unhappy urban landscape.

about evils of drinking or sin, then it is a story of a lost individual: It is about one man’s inner violence and search for redemption. The Phantom Carriage is not plagued by preachy morals and as a result there is no easy reading of the film’s uplifting conclusion. This ending is weighed down by the overbearing darkness that precedes it and does not feel like a strong consolation for this unhappy urban landscape.

Those fond of the work of Ingmar Bergman will see a lot of the foundation for his spiritual aesthetic here. Sjostrom would go on to make films in the United States such as The Wind (1928) and He Who Gets Slapped (1924), and is only in recent years gaining appreciation for his complex narrative and visual schemes. His films are played out in extremes but remain relevant and exciting due to the truth in the spiritual and emotional trajectories of his characters.

– Justine Smith