The Flat

Directed by Arnon Goldfinger

Written by Arnon Goldfinger

Israel and Germany, 2011

Curiosity can easily be a curse. No matter what you’re so interested in, the message we get from modern popular culture is that, somehow, we’re better off not knowing the full truth. So why even ask the questions? You may think you have good intentions in whatever fascinates and compels you, whatever you’re prying about, but finding out the truth may set you back more than when you could claim ignorance. That’s one of the many points being made in the intriguing new Israeli-German documentary The Flat, about how a man’s honest attempt to clarify his family tree spirals into something disastrously life-changing.

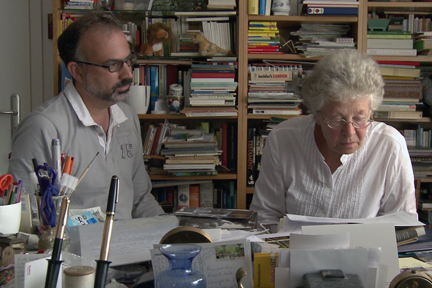

Writer-director Arnon Goldfinger, at the beginning of The Flat, begins the process of cleaning out his recently deceased grandmother’s apartment in Palestine, a place she lived in with her husband, Goldfinger’s grandfather, for about 70 years. While doing this, he gets more compelled by what his grandparents did when they arrived in Palestine after emigrating during the rise of the Nazi party in Germany in the early 1930s. One thing leads to another, and he soon finds a strange connection his grandfather, Kurt Tuchler, appears to have had with a Nazi named Leopold von Mildenstein. Goldfinger can’t fathom why his Jewish grandparent would be, for example, shepherding von Mildenstein around the part of Palestine where Zionists wanted to set up what would eventually become Israel. Through dogged and persistent investigating, Goldfinger gets closer to the truth in ways he can’t believe or control.

Perhaps the most impressive part of The Flat is that Goldfinger, both as documentarian and as its consistent face, rarely, if ever, gets heated or lets his emotions run too high. As he travels around the Middle East and Germany, trying to get to the bottom of this peculiar mystery, Goldfinger sometimes lets his general bafflement get the better of him, but for the most part, he doesn’t get angry. As the film progresses and he gets conflicting information from one family member or friend of a friend of von Mildenstein or Tuchler, what’s fact and what’s speculation gets murkier. As a screen presence, though, Goldfinger is somewhat calming, able to reflect his genuine interest even if the story gets darker than he ever imagined.

A question that becomes present, especially in The Flat’s second half, is whether or not Goldfinger wants the responsibility of telling people about their family’s past, tell them something they never thought possible. Does Goldfinger deserve this responsibility? Does he want it? Should anyone have that task? The way that he’s able to document his inner frustration, as well as the visible denial on the faces of the people he’s visiting, is the film’s best aspect. Goldfinger’s ability to not lay it on too thick, to not editorialize unnecessarily or pump the film full of false emotion, is another strong suit, but his unflinching willingness to present this entire story, warts and all, is stunning.

Another compelling reaction Goldfinger captures in The Flat is one he sees in almost everyone he encounters, especially those who are demonstrably older than he is. The attitude they exude, something close to knowledgeable nonchalance about how German and Jewish history collided so violently in the 1930s and 1940s, and of its innumerable effects, is shocking. Goldfinger manages to contain any surprise—it’s alluded to more than directly represented—but the manner in which he is dealt with by these people and his deliberately low-key reactions are equally gripping and maddening. The basic tone they exude is that age equals maturity, that being old means you automatically know better, which is clearly not the case.

The Flat is an inherently sad film, a documentary that started out as something small, something kind and honest: an attempt to show a family the life their eldest member lived. Goldfinger’s innate curiosity is something of a personal undoing; first, he knows too little, but he ends up knowing far too much. Is it better to learn about all of your family members’ personal demons, the secrets they forcefully tried to hide from those around them for years, or to keep only their fabricated image in your mind? Though the truth is unearthed in The Flat, Goldfinger and his family may have been better off living a lie.

— Josh Spiegel