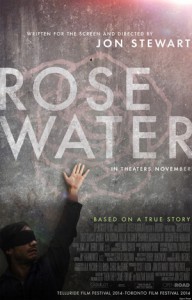

Rosewater

Rosewater

Written for the screen and directed by Jon Stewart

USA, 2014

Rosewater, the directorial debut of The Daily Show host and stand-up comedian Jon Stewart, is a modest retelling of one man’s prolonged imprisonment for honestly reporting about Iran. It’s an engaging exercise about political transparency made possible by the modern media that’s obviously close to Stewart’s heart. This is serious content interlaced with sporadic interludes of comedy that in Stewart’s hands sails smoothly along without seeming inappropriate or misplaced.

The amiable journalist Maziar Bahari (Gael García Bernal) falls into the role of responsible witness while filming protests that turn deadly following the questionable re-election of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad as the President of Iran. Bahari spending time with citizens who oppose Ahmadinejad to get a broader perspective for his writing, forwarding the bloody protest video to media outlets, and taping a silly interview for The Daily Show all build up to Bahari becoming a person of interest for the oppressive government. With Bahari suddenly taken into custody, an Iranian official is chosen to break the journalist’s will and make him confess to being a Western spy sent to facilitate unrest by spreading false information.

Stewart shows genuine respect for what his friend had to ride out. By delineating Bahari’s love and commitment to his family at length he also explicates the real stakes that were at hand. Rosewater is the personal journey of a quiet reporter who has endured a lifetime of suffering, losing both his father and sister to the terror of previous regimes in his home country. Knowing very well what could happen to him, the story sincerely spells out Bahari’s torn mindset and works with it to create the small, emotionally resonant world of the film.

The movie is careful to point out over and over that what he experienced was a cakewalk compared to the atrocities underwent by many victims of the government who will never have their stories told. Rosewater doesn’t remotely approach the brutality of the torture seen in something like Zero Dark Thirty. The film instead sticks to the facts of the extreme psychological distress that the journalist withstood, being in the privileged position of an international pawn. This is hardly the most provocative or memorable performance from Bernal, whose lively eyes coupled with the restless souls he’s portrayed have been so ingrained in the collective cinematic consciousness in such films as Amores Perros and Y Tu Mamá También. Still, Bernal makes his strain under confinement plausibly dignified with brief glimpses into the true depth of Bahari’s mental anguish from isolation and fear of the unknown. A sequence involving Bahari expressing himself to a Leonard Cohen song stands out and particularly lifts the audience out of the monotony of the prison cell. This and other brief flourishes of comedy ease and refresh the tension, elevating the film beyond the status of a forgettable adaptation.

Rosewater is a competent and well-made depiction of Bahari’s ordeal that holds promise for Stewart in terms of its ideas and earnestness. Solid but unable to climb the peak to greatness, it’s compelling but bogged down and slightly underwhelming because its overall content is resolutely mild. One gets the feeling that Stewart is largely reserved in his first outing due to his solemn appreciation for Bahari, but if given the right material he could spin something truly jaw-dropping. Remaining strongly in the background are the yearnings for freedom from tyranny that only come across from periphery characters who graze the journalist’s path or the peaceful but dissenting crowds whom the repressive government refuses to hear. This leaves Bahari’s intimate pain the main subject in play. The value of holding fast to human rights with the aid of social media is clear to see, but would have benefited by being attached to the exploration of the fate of someone less fortunate than Bahari.

Stewart and Bahari take their media responsibility and visibility in all seriousness, knowing that even a comedic piece (like the one Bahari participated in) can affect the outcome of people’s lives. As in The Daily Show, there may be may be some superfluous scenes here, but it’s certain that there is import in reiterating that information is power and should be an inalienable right. Stewart’s articulate understanding of our age of hyper-communication is a significant commodity that will hopefully crop up again in a less gentle and restrained turn on the screen.

— Lane Scarberry

Visit the official website of the Toronto International Film Festival.