Hollywood history always makes for fascinating reading. Hindsight and whatnot. During a month in which Sound on Sight takes an opportunity to tip a collective hat in the direction of recently ‘retired’ workhorse auteur Steven Soderbergh, there is a further chance to reel back the years and examine a period of time when one of modern cinema’s finest acolytes was transforming from indie hero to mainstream heavyweight. Of course, it all seems so predictable now that he would follow up his 2001 Oscar win with 12 years of financial and critical success with unmatched versatility. What is more interesting are two fellow directors sharing the limelight with him that year, the trio hailed as the hottest directorial properties in the business. Chances are many of you do not remember the name Richard Kelly. It’s likely most of you have no wish to recall the work of M. Night Shyamalan. 2001 was a strange year.

Hollywood history always makes for fascinating reading. Hindsight and whatnot. During a month in which Sound on Sight takes an opportunity to tip a collective hat in the direction of recently ‘retired’ workhorse auteur Steven Soderbergh, there is a further chance to reel back the years and examine a period of time when one of modern cinema’s finest acolytes was transforming from indie hero to mainstream heavyweight. Of course, it all seems so predictable now that he would follow up his 2001 Oscar win with 12 years of financial and critical success with unmatched versatility. What is more interesting are two fellow directors sharing the limelight with him that year, the trio hailed as the hottest directorial properties in the business. Chances are many of you do not remember the name Richard Kelly. It’s likely most of you have no wish to recall the work of M. Night Shyamalan. 2001 was a strange year.

The three men had undoubtedly reached a pinnacle by then. Having earned a solid reputation and cult following with a series of subversive, voyeuristic fables (headed by Sex, Lies & Videotape), Soderbergh graduated to the big time with Oscar success for his superlative 2000 epic Traffic and coveted biopic Erin Brockovich (the former for himself and his movie, the latter for star Julia Roberts). Critical plaudits were to be followed by financial pull, as he set about a star-studded remake of the 1960 heist caper Ocean’s 11. Meanwhile, Shyamalan blasted on to the scene in some style with 1999’s The Sixth Sense, undoubtedly one of the 1990s biggest and most unexpected hits, and followed it up with the warmly received and conceptually superb Unbreakable the following year. Now his third project, crop circle thriller Signs, was in production. His achievements compelled Newsweek to call him the “next Spielberg”. Finally, Richard Kelly had enjoyed a similar meteoric rise after striking a nerve with his fantastic ‘g”owing pains with alternate dimensions” drama Donnie Darko. A young director harnessing so many storytelling elements so effortlessly in a sea of nostalgia was never going to go unnoticed. The only way was up…

Or so it seemed. On paper, there was no reason why all three couldn’t prosper, and the fact only one emerged from the age of potential with honors still appears to be something of a mystery. Soderbergh may have played the game somewhat in ensuring his longevity (the Ocean’s films quickly degenerated into a financially oriented merit vacuum), but justified it by displaying a nose for various genres and cinematic cliques that could draw comparisons to Stanley Kubrick. This versatility – shown by the contrast between the likes of Contagion, The Girlfriend Experience, Haywire, The Informant and Side Effects – is a skill that made him incomparable to other directors. It is also a trait that should have been applicable to Shyamalan, who unfortunately only reads as a master of genres on paper. His resume is incredibly impressive when the quality of his work isn’t taken into account. His body of work consists of, respectively, horror, supernatural thriller, alien invasion, faux-historical drama, fairy tale re-imagining, apocalyptic epic, comic book tale and hard sci-fi. He’s also worked with stars such as Bruce Willis, Will Smith, Samuel L. Jackson, Mark Wahlberg and a pre-pariah status Mel Gibson, suggesting a creative passion sufficient to sway and enlist big names with everything to lose.

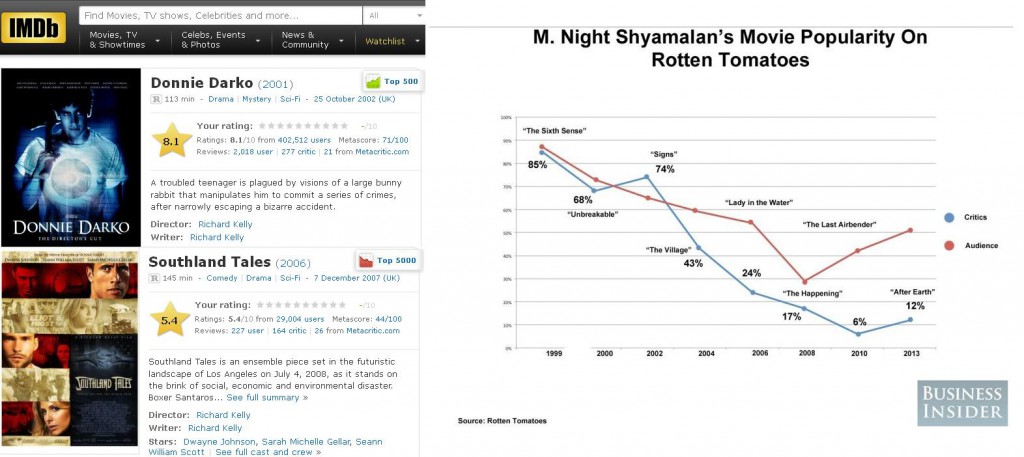

And lose they did, unfortunately. While Soderbergh deserves credit for building George Clooney into a highly respectable actor rather than just a star, and for playing a big part in the re-genesis of Matthew McConaughey’s career, Shyamalan curtailed a similar ascent for Paul Giamatti and ended the brief clamor for Wahlberg as a serious presence following his Oscar nom for The Departed. Everything fell apart gradually and with spectacular levels of bizarre and banal, he took everyone down with him. Signs proved to be divisive in a manner not seen with his first two films, with some loving its storytelling smarts while others mocked the bizarre dialogue, dodgy plotting, and contrived use of backstory. The Village slumped further toward the negative school of thought with a predictable twist and some ramshackle acting from a respectable cast. He hadn’t progressed as a filmmaker; if anything, he had gone backwards with a lack of innovation, inferior writing skills, and an inability to work without his ace in the pack, the final twist.

This all came to a head in 2006, at which point his career trajectory linked up with another young director about to commit professional suicide. Although Donnie Darko had as far been his only major film and been followed by a 5-year hiatus, Richard Kelly was in serious trouble. While Shyamalan’s decline had been drawn out over a busy period of time comprising four films and multiple stars, Kelly only needed one project and the inability to attract any respectable names. This was Southland Tales, or to give it a more deserving full title, “The Southland Tales Debacle.” That long wait since Darko had led many critics to believe he was brewing something big and something spectacular, which was proven correct with Tales, an epic near-future end of the world parable pitting the rapture in a decadent Los Angeles. Unfortunately, a long and meandering story was ripped apart at Cannes by bemused critics, some of whom booed its closing credits, forcing Kelly underground to try and rescue his baby in the editing suite. It didn’t work. A final cut emerged in 2006 for a limited release 4 months after Shyamalan’s Lady in the Water and was ravaged once more.

Both films, in fact, were not treated kindly. Shyamalan took a new approach to Lady, ditching his use of big names in favor of a more compact character actor-led cast (Giamatti and Bryce Dallas Howard to the fore) and doing away with the need for a big plot twist to define the story. These factors counted against him, though, since the fairy tale fell badly short of quality, interest, or logic. While the script was clearly its weakest component, ill-thought-out, and showing a lack of restraint that would embarrass Quentin Tarantino, Shyamalan sealed the deal of a commercial and critical bomb by not only taking a petty dig at film critics who championed him for years, but also casting himself as a messiah figure. It was the ultimate example of hubris and the final nail in his coffin. “No longer is this a filmmaker of immense promise and talent merely suffering a slump,” the back pages said “In fact, he is a self-obssessed hack finally exposed as a one-hit wonder.” Such a cutting indictment would be considered harsh were it not for the fact that Shyamalan’s winter of discontent would not end that year.

Kelly’s effort, in many ways, is worse than Lady in the Water while proving to be much more fascinating. There is some intrigue in its premise, in some of its ideas, but the calamitous execution kills any hope of something other than a cinematic disaster. Like Lady, it suffers from being a decent concept lost in a bad screenplay, and is only salvageable by its visuals and its direction. Unlike Lady, it features Dwayne Johnson and Seann William Scott as protagonists and uses a supporting cast of Saturday Night Live performers to bewildering, humiliating effect. A film that opens with a nuclear strike in Texas and deals in parallel dimensions and end days is somewhat undermined by the sight of Jon Lovitz as a villainous corrupt cop, Justin Timberlake as a crazed war veteran performing Killers songs apropos of nothing, and Stifler as the would-be savior of mankind. The sheer level of Caligulan depravity and debauchery as failed gambits pile into creative mistakes is almost too much to bear when coming from someone capable of so much more. While quite incredible to watch, the film is no more in debt to its quality than The Room.

Elsewhere, Soderbergh was taking it easy. This was during a 2-year period of reflection comprising one foray back into the indie market, a short film and The Good German, a retro post-World War II black-and-white noir that represented not so much a gamble as an enjoyable folly. This preceded the brightest spell of his career, starting with his completion of the Ocean’s trilogy and closing (for the time being) with the wonderful Behind the Candelabra. After numerous big hits that easily overshadowed his lower ebbs (Full Frontal the most notable), he could afford to take stock. The contrast is astonishing. While Soderbergh went on this plush run, Shyamalan finally sealed the deal on his career by making his three worst films. Kelly, unable to earn as many second chances, only had one stab at redemption; the horrifically mediocre The Box. He hasn’t made a film since. While he ended up in the wastelands, Shyamalan earned comparisons to Ed Wood with The Happening and The Last Airbender, and ended up being the stooge in this year’s Will Smith vanity project (and catastrophic wreck) After Earth. The irony is that in 2001, all three men had the world at their feet; in 2013, none of the three face the prospect of making any more films for bizarrely different reasons. Soderbergh is retired. Kelly has been retired. Shyamalan is unemployable.

The big question is why, not how. It is clear to see from box office receipts and critical aggregate scores how they all went in such directions, but the cause of that disparity is rather harder to figure out. Soderbergh, while occasionally prone to taking too big a risk, is undoubtedly hugely talented, able to brilliantly judge a story and figure out it can best be put on screen. It doesn’t matter whether this method be documentary-like impartiality or hard-boiled imagery, he has the smarts and the means to make it work. His success is no mystery, and has been on the cards since the early 90s. Shyamalan’s failing should be visible to any fan of film. The man clearly has genuine ability as a director, with a great visual eye and sense of atmosphere. The Sixth Sense may be best remembered for its shock ending, but it stands up as an excellent horror drama due to the manner in which the material is shot and handled, with a great eye for detail and great composure when dealing with the scares. Even the worst of the worst, After Earth, has some nice visual touches and a good use of cinematography. The problem is in the writing. Shyamalan knows a good story, he just doesn’t know how to tell it. The Sixth Sense worked, but everything else since has been brought down by his screenplay, with a combination of awkward dialogue and lack of logic devaluing the overall piece. The Happening is easily one of the worst written films of the late 2000s, so bad it managed to make the likes of Zooey Deschanel look like dreadful actors. His reputation may be in the toilet now, so advice is a little worthless, but had he chosen to direct somebody else’s script his name now may not be synonymous with failure. It may just be that simple. “The Next Spielberg,” in retrospect, should have read “The Next George Lucas.”

Richard Kelly is harder to fathom. Donnie Darko will go down as a one-hit wonder, remembered as a brilliant film with an indie spirit and high concept look, while its director won’t be remembered at all. It only took one film to kill his career, while Shyamalan took six. The talent was always there, and is hidden within the multi-car pileup of Southland Tales. It seems a misstep, a gross misjudgment of what made his magnum opus work. People were compelled by the exploration of teen angst and ambiguous subtext (as well as the career-making turn by Jake Gyllenhaal) rather than talk of tangent universes and semi-biblical explorations of time and space. Even when this was interesting, it was presented by good actors reading a good script in the midst of a fascinating mystery. It wasn’t The Rock as a quasi-James Bond. In hindsight, Kelly should have been given another go. Then again, hindsight and whatnot. Perhaps next time, we should be a little more careful about who we hail as the next big thing. Not everybody can be a Steven Soderbergh, after all.

— Scott Patterson