Picking the best movies that come out in any given year is no easy feat. For film fans, a quality feature can come out at any time, from any one, and discovering an enjoyable and well-crafted feature is truly a pleasure. As we reach the halfway point of the year, many excellent films have already made their way to theatres, films that are well worth a watch. Below, you shall find the list of the top 30 films of 2014 to date, a list that ranges from science fiction thrillers to period dramas.

A few notes to keep in mind when reading our entry: Certain films from our 2013 list make a second appearance on this list. This is because the movies, while technically released this year, were seen by a select few in time for last year’s list, due to the benefit of film festivals and press screenings. The list itself is in no particular order, as quality trumped ranking for us when organising the list, and the fact that 30 films already made the cut is a testament to the strength of this year in film. That being said, our top two films were runaway winners, with our top choice edging out our runner-up by merely a single point, and the difference between our second and third choice being a much wider gulf, though the difference is not a slight on the quality of our third place finisher, but rather a testament to the strength of our silver medalist film.

#30. How to Train Your Dragon 2

Directed by Dean DeBlois

Written by Dean DeBlois

USA

DreamWorks Animation returns to the world of dragons and Vikings in this sequel to their 2010 hit How to Train Your Dragon. Here is a rare sequel, that exceeds the charm, whismy, and intelligence of the original. How To Train Your Dragon 2 builds on its predecessor’s successes and in the end, the film is funnier, deeper and more emotionally powerful than the original.

– Kyle Reese

29. Borgman

Written by Alex van Warmerdam

Directed by Alex van Warmerdam

Netherlands

The home invasion thriller has been around for decades already, shocking audiences worldwide with creepy tales that speak to the fear that lies in many hearts: maleficent strangers attacking one’s most private domain. The classics of the genre are well known: Panic Room, Funny Games, Black Christmas, Home Alone, etc. Dutch writer-director Alex van Warmerdam throws his hat into the ring with Borgman, a unique variation of the genre that handedly distances itself from the fray.

Yes, the overarching plot of Warmerdam’s Borgman is about how the titular protagonist (Jan Bivoet) and his posse attempt to infiltrate the modern house of a upper middle class Dutch family already living under some strain. On face value this alone offers little new. However, as the saying goes, it is the journey that matters rather than the destination, and what a journey the director has in store. Eschewing notions of a straightforward telling of the invasion process, the director adds a supernatural twist and keeps the audience guessing as to what might happen next with a series of increasingly unexpected developments and visual cues. Star Jan Biveot takes center stage as the ringleader guiding his team to overtake the targeted family not through brute force but with trickery of the mind and heart. The extent of the metaphysical powers he and the other fiendish group members possess is never explained, making each plot revelation as appropriately ghoulish as they are surprising. What Borgman is matters less than what he does and how. Biveot is an unnervingly magnetic presence, the perfect foil for an unsuspecting family and showcases a strange charisma that will have audiences falling for him just as do the damned victims in the film itself.

-Edgar Chaput

28. Jodorowsky’s Dune (2014)

Directed by Frank Pavich

USA

Director Frank Pavich doesn’t just pay tribute to director Alejandro Jodorowsky’s lunacy, but to the general lunacy that comes with the artist and his pursuit to create the ultimate masterwork he’d envisioned. Long before David Lynch gave the world his version of the novel Dune, director Alejandro Jodorowsky set out to create his own unique version of the novel. It would embrace the inherent madness of the world conceived by Frank Herbert, but also change the way we looked at science fiction cinema.

Alejandro Jodorowsky, who’d blown minds with his method of subversive and reality altering cinema for years before hitting his stride with El Topo, took on the epic series of Dune in the hopes of molding the world’s mind set of science fiction. He didn’t want to make a movie, he wanted to build an experience that would warp us in to a distant galaxy built upon decadent clothing, way ahead of their time ideas, and a slew of artists and actors Jodorowsky called his “spiritual warriors.” He assembled an impressive crack motley crew of amazing visionaries, including Mick Jagger, Moebius, Pink Floyd, Salvador Dali, and HR Giger, to name a few. All of whom would contribute to the legacy of a film Jodorowsky was so passionate about that he even put his own son through torturous sessions of fight training and survival to master his role in the movie.

Jodorowsky is never shy about recounting his experiences creating his vision of Dune, explaining how his film would change the world forever, and recalls wonderful anecdotes. Among them are his chance meeting with artist Moebius, and his angry shouting at the band Pink Floyd when, during a recruitment session with him, they chose to snack on MacDonald’s Big Macs. You garner a true sense of respect for Alejandro Jodorowsky who views his film as the one movie that would change the world, and was halted by short sighted Hollywood producers. It’s a fun, and often mesmerizing look at a man whose vision likely would have transformed science fiction entirely, whether it succeeded or failed in theaters. If you’re a filmmaker of any kind, Jodorowky’s Dune is a must watch, if only for its insight on filmmaking and collaboration.

– Felix Vasquez Jr.

Directed by Steve James

USA

Perhaps an even greater tearjerker than The Fault in Our Stars, Steve James’ Life Itself is a celebration of the life of everyone’s favorite film critic Roger Ebert. James is unafraid to show Ebert at his worst, both in his behavior as a competitive and caustic journalist and former alcoholic and in his physical condition undergoing suction from his throat as treatment for his cancer. While loosely based on Ebert’s autobiography of the same name, Life Itself finds depth as a documentary exploring movies, film criticism and most notably the people Ebert’s life touched. Everyone from Errol Morris to Werner Herzog to Ramin Bahrani and Richard Corliss are on hand to pay their respects, and it’s a touching remembrance whether you’re a cinephile or not. But it’s most importantly a film about Roger the man more so than just the critic, and James finds room for sweet stories about Ebert’s Chicago Sun-Times colleague Bill Nack and how Ebert came to be a father figure for his wife Chaz’s children and grandchildren.

Life Itself is the perfect tribute to Ebert’s memory because it doesn’t just fawn over him but it feels as though it is him. It’s warm, loving and funny but also deep, critical and flawed. It’s hard to say if Ebert would’ve loved this movie, but he would have known it all too well.

Brian Welk

26. Starred Up

Directed by David Mackenzie

Written by Jonathan Asser

UK

David Mackenzie’s Starred Up unravels the complex emotional incompetence and stubbornness behind the actions of prisoners. Packaged in blood-soaked spectacle, the film dissects the prolonged impact of confinement and the poor choices of hardened felons who strain to have avenues besides violence to effectively communicate their frustrations. The content stuns with its ferociousness but in no way makes excuses for the crimes that they’ve committed or the acts they’ve perpetrated in order to find a favorable place in the pecking order of prison. Jack O’Connell (Eden Lake) plays Eric, a juvenile delinquent making an uneasy transition into the adult prison system. Winding up in the same prison as his estranged father Neville (The Place Beyond the Pine’s Ben Mendelsohn), the story cleverly veers Eric away from any kind of heartwarming reunion. The hopelessness of indefinite incarceration compounds with bitter feelings to successfully turn the tension into a palpable gauntlet of spontaneous brutality. This creates a terrifically claustrophobic atmosphere where O’Connell’s virulent fury and Mendelsohn’s rage (that is visibly tempered only by age) boil into toxic situation after toxic situation. Impulsiveness impressively reigns over every scene as the duo jumps at almost every chance to destroy each other or anyone who dares to cross them. Empathetic therapist Oliver (Rupert Friend) attempts to curtail the needless savagery by making Eric and Neville examine themselves. The brilliance of the script by Jonathan Asser comes from how the veracity of the confrontations don’t magically resolve grudges or mend broken relationships. Instead, they spawn a thoughtful examination of how the ill effects of violence can reverberate through generations. The characters possess a twisted dignity behind their desperation and unwillingness to positively change that is as admirable as it is sick. The movie’s rough subjects disrupt the notion of what constitutes affection and the plot is smartly aimed away from any notion of conventional atonement for misdeeds. An unflinching portrait of primal rage and survival, Starred Up is hard to absorb but a memorable ride into the unexpected.

– Lane Scarberry

25. The Great Beauty

Directed by Paolo Sorrentino

Written by Paolo Sorrentino

Italy

Director Paolo Sorrentino wears his influences on his sparkling sleeve. Fellini, Lynch, and Almodóvar all dance among the ruins of contemporary Rome in The Great Beauty, 2014’s Oscar winner for Best Foreign Language Film. The movie can be dizzying, saturated with color and overstuffed with characters, documenting a creative class who no longer create, restless citizens of a city whose best days are behind it. It’s almost as if these people are afraid to stop moving, convinced they’ll turn into one of the crumbling monuments looming behind them and die. Toni Servillo’s grounded central performance keeps the whole thing from bursting at the seams. His Jep Gambardella, a former literary it boy who stopped writing but never stopped celebrating, would be tragic if he wasn’t so hopeful. At 65, he’s still the eternal optimist, darting from party to party and lover to lover, slowly realizing he wants more from life than his fading reputation and a gorgeous penthouse in the shadow of the Coliseum. The Great Beauty proves that coming-of-age stories aren’t always wasted on the young.

– Bryan Rucker

24. Night Moves

Written by Kelly Reichardt & Jonathan Raymond

Directed b Kelly Reichardt

Since 2006, Kelly Reichardt has found a way to reach inside of the hearts of her audiences, plucking out strings one by one with desolate re-imaginations of the American Pacific Northwest, seen through the eyes of people not so different than ourselves. With Meek’s Cutoff, she departed from her typical genre and moved in to the old west, but you could still see her stark realism, perfectly imagined on screen. Now, Reichardt has shifted gears again, this time to present day (still in the Pacific Northwest), following three environmental activists as they plan to blow up a dam. But this time, Reichardt has eschewed all sense of dry, dirty characterization for a much more flowing story where the characters emerge from their settings more fully. It’s still methodical, but somewhere in between the planning and heist itself, Reichardt’s star Jesse Eisenberg finds notes we haven’t seen from him since The Social Network, diving into an emotional core than feels altogether genuine. Supported by an equally brilliant Dakota Fanning and, to a lesser (but still interesting) extent, the unsettling Peter Saarsgaard, Eisenberg helps Reichardt deliver one of the more stunning shifts in genre from an already established filmmaker in recent memory, without fully forgetting what made her films so successful in the first place. The film feels like something from another era – a pseudo-noir that feels more like a 1970’s Lumet or Frankenheimer detective film.

– Joshua Gaul

23. The Wind Rises

Directed by Hayao Miyazaki

Written by Hayao Miyazaki

Japan

In The Wind Rises, Jiro dreams of flying and designing beautiful airplanes, inspired by the famous Italian aeronautical designer Caproni. Hayao Miyazaki has long been regarded as the world’s premiere animator. The Wind Rises is his eleventh animated film as a director, and may be his last. If so, it’s a fittingly bittersweet swan song for the filmmaker. In terms of tone, visual beauty, and storytelling, The Wind Rises ranks among his very best – and maybe his finest achievement.

– Kyle Reese

22. Noah

Directed by Darren Aronofsky

Written by Darren Aronofsky and Ari Handel

USA

Noah is a big, messy film, but the essence of what makes it special can be found in one scene: the creation sequence. Though narrated by a weary Noah already in the ark, visually, the film takes a detour as biblical and evolutionary imagery mesh together while the camera rushes with blinding speed through time and space as the world emerges and Adam and Eve come into being, quickly followed by temptation, the fall, sin, violence and destruction. The shots of a silhouetted Cain striking down Abel as they transform into soldiers from several wars throughout history is a sight that has to be seen to be fully appreciated, and it would have been enough to make Noah worthwhile. What the sequence and the shot reveal is Darren Aronofsky’s willingness to engage his source material, to take tradition, history, religion, and science seriously all while telling the gripping story of one man’s struggle to come to terms with his fallen, violent nature. Whatever it’s flaws, Noah could never be accused of being a movie by committee. It is the singular, unfiltered vision of one man, which is more than can be said of any other Hollywood movie made at this level in quite some time.

Antonio Jose Guzman

21. The Double

Directed by Richard Ayoade

Written by Richard Ayoade

UK

There’s nothing quite like Richard Ayoade’s The Double; a bittersweet, quizzically grim puzzle box of a film that taps into the heart of our bureaucratic messes and statistically-bound, faceless lives. Eisenberg and Wasikowska’s performances elevate what could’ve otherwise been an otherwise cold arthouse exercise into something surprisingly poignant. It’s a pity Ayoade struggles to do the same; he is at times, more enamoured with his Gilliam-lite set and riffing off identity than he is in James’ story.

– Vivienne Mah

Directed by Sang-soo Hong

Written by Sang-soo Hong

South Korea

Hong Sang-soo’s Our Sunhi (2013) is his fifteenth film since he began directing in 1996. Our Sunhi is about a young woman asking for a letter of recommendation from a film school professor so she can go to graduate school in America. From this banal starting point Hong weaves an intricate and deceptively simple narrative about male desire.

Sunhi is played by Jung Yumi, Professor Choi Donghyun is played by Kim Sang-joong, Munsu is played by Lee Sun-kyun and is a film director and Sunhi’s ex-boyfriend. Jaehak is played by Jung Jae-young and is an acquaintance of Sunhi, he also knows Munsu but does not really like him, and is good friends with Professor Choi. Jaehak is also separated from his wife at the moment. Jaehak, like everyone else is the film is also a filmmaker but appears to be more established than Munsu. Jaehak is fairly dismissive of Munsu (maybe because he knows Munsu dated Sunhi) and is more friendly and generous to Professor Choi (maybe because he does not know Choi is infatuated with Sunhi). Hong interweaves several conversations between the four characters, repeating lines of dialogue, actions, and scenarios with subtle changes, challenging the spectator’s memory of what they saw from earlier scenes as we learn about how these three men desire Sunhi.

What begins as a film about a reference letter on Sunhi’s character opens up a male discourse on Sunhi. The title Our Sunhi perfectly captures what this film is about: three men continuously describing a woman but never fully comprehending her.

19. 22 Jump Street

Directed by Phil Lord and Chris Miller

Written by Michael Bacall and Oren Uziel

USA

Besides being the hardest I’ve laughed in the theater this year – and likely the rest of the year – 22 Jump Street was also a marvel of meta self-referential filmmaking. Just as the first mocked itself for being a cash-grab adaptation of a ridiculous TV show, directors Phil Lord and Christopher Miller brought their anarchic comedy to craft a comedy sequel that managed a commendable feat – it felt fresh by acknowledging how stale the whole endeavor of a comedy sequel normally is. This mindset has been the biggest gun in Lord and Miller’s arsenal throughout their filmography, and they brought more than they have in 22 Jump Street than they ever had. It got excessive and unnecessary at points, but you’re having such a fun time with Jonah Hill and Channing Tatum playing off each other you really don’t care. The references aren’t just efforts to excuse themselves from criticism of the trope they’re about to riff off of, it’s an opportunity for them to break new comedic ground on the trope they’re about to riff on. Phil Lord and Christopher Miller create films where you’re not just laughing at the film, you’re laughing with it.

Dylan Griffin

18. Ida

Directed by Pawel Pawlikowski

Written by Pawel Pawlikowski and Rebecca Pawlikowski

Poland / Denmark

At a scant 80-minute running time, Ida appears unable to afford the lengthy silences and somber inactivity that it offers to audiences. Nevertheless, this story of a novice nun’s journey to discover her identity resonates with an immense emotional weight. The brilliance of the two lead actresses is partially responsible for this success, as they both quietly display the inner turmoil of their characters. But the rest of the victory goes to Paweł Pawlikowski, who uses delicate camerawork and a black-and-white palette to strip his film down to the core of minimalism. He forgoes superfluous style, allowing the poignancy of the story to wash over the audience.

– Jacob Carter

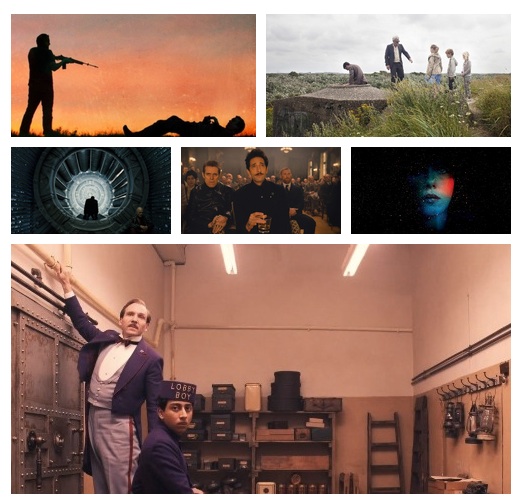

17. Enemy

Directed by Denis Villeneuve

Written by Javier Gullón

Canada / Spain

Enemy, Denis Villeneuve’s eerie tale of doppelgangers sets Toronto as a decaying dystopian metropolis. After watching a movie, a history professor becomes obsessed with tracking down an actor who looks exactly like him. Based on a novel by Portuguese Nobel prize winner, Jose Saramago, the film casts doubt on individuality and identity in the contemporary world. Blending surrealistic imagery and a foreboding sense of doom, this film returns Villeneuve to his more fantastical early works like Un 32 Aout sur Terre and Maelstrom, where he explored modern life through veils of mythology, fantasy and chance. The film opens with a haunting opening sequence that harkens to the opening of Bergman’s Persona, and never has contemporary Canada looked as bleak then in the height of Cronenberg’s oeuvre. Enemy bends and manipulates reality for the characters and Villeneuve translates that through an uncomfortable pacing that draws uncomfortable patterns and repetitions. While the idea of the doppelganger is not a new one, to tie it so frankly to time and space brings new nuances that few other filmmakers have evoked. The apocalyptic tendencies of Enemy in particular, reflect a fairly daunting understanding of the characters’ interior worlds.

– Justine Smith

16. Her

Directed by Spike Jonze

Written by Spike Jonze

USA

15 minutes into the future, Los Angeles, and Theodore Twombly (a subdued Joaquin Phoenix) is a quiet, reserved young man who works as a letter writing intermediary in some pastel hued start-up. Theodore is in the final throes of an exceptionally painful divorce to his childhood sweetheart Catherine (a porcelain Rooney Mara), briefly glimpsed flashbacks detailing their genuine love for each other slowly eroded by his reserved inability to articulate his emotions, to make a lasting and bonding connection. In this world computers have become even more ingrained into our society and civilisation, organically subsumed into the fabric and environments of society and culture, with a new iteration of self-aware Artificial Intelligences released on the market in order to aid in the organisation and functional efficiency of our lives. Theodore boots up a new OS voiced with the Bronx-born purr of Scarlett Johansson, she self-christening herself as Samantha as an affectionate bond grows between the physical and digital, an organic ardour which initial stretches credulity but gradually becomes convincing.

This genuinely moving, fearless film takes its implausibly ridiculous premise and makes it believable and genuine,displaying a new-found maturity and skill from director Spike Jonze’s imagination. Whilst it neutrons fire through the usual rom-com code it feels fresh, even as the ‘best friend down the hall with her own romantic complications’ act as a greek chorus to the central romance, as the first flushes of initial romance are expressed through some giddy dates on the beach and at the fair. It’s fearless in tackling head-on the rather sticky subject of consummation of the romance, examining how we may interact and grow with our technology in the years to come, and the restraints inherent of the bonding of any two entities. Phoenix is an abrupt 180 degree turn from his recent volcanic performances, a slightly meek, withdrawn but affectionate man, a performance amplified by the soft and subtle shooting techniques which suggest Theodore’s isolation and dislocation through reflections and framing, whilst the films Arcade Fire soundtrack thunders in the background like the distant patter of rain on windowglass.

Her posits a number of contemporary questions, of accepting someone for whom they are and all their intrinsic qualities good and bad, or on a more sociological level a film about how we live now, how our tools and gadgets refract back our own humanity and emotional requirements, and crucially how these tools and advances cannot satisfy certain core requirements or at the very least are warped and refracted around such intangible concepts as ‘love’. This is a warm, melancholy and moving film which manages to exceed its potentially ridiculous premise, of how technology can simultaneously bring us together even as it sets us apart;

– John McEntee