In 1963, Film Quarterly published an essay entitled “Circles and Squares.” It addressed the French auteur theory, introduced to America by The Village Voice’s Andrew Sarris. Auteurism holds that a film’s primary creator is its director; Sarris’s “Notes on the Auteur Theory” further distinguished auteurs as filmmakers with distinct, recurring styles. Challenging him was a California-based writer named Pauline Kael.

Kael attacked Sarris’s obsession with trivial links between filmmaker’s movies, whether repeated shots or thematic preoccupations. This led critics to overpraise directors’ lesser films, as when Jacques Rivette declared Howard Hawks’ Monkey Business a masterpiece. “It is an insult to an artist to praise his bad work along with his good; it indicates that you are incapable of judging either,” Kael wrote.

She criticized auteurist preoccupation with Hawks and Alfred Hitchcock, claiming critics “work embarrassingly hard trying to give some semblance of intellectual respectability to mindless, repetitious commercial products.” Nor did she agree that a strong personal style made a great director. “The smell of a skunk is more distinguishable than the smell of a rose,” Kael asked: “Does that make it better?”

“Circles and Squares” catapulted Kael from Berkeley cineaste to national figure. It encapsulated her unique style: verbose, witty, daringly contrarian; also hyperbolic, blunt, even insulting. It also showed her impatience with critical dogma: why credit a director and ignore the impact of stars, screenwriters, photographers, composers – even audiences?

These traits sustained Kael as America’s leading critic for three decades, writing for McCall’s, The New Republic and, from 1967 through 1991, The New Yorker. She championed controversial films like Bonnie and Clyde while excoriating blockbusters like The Sound of Music. Her confrontational style provoked controversy, won fans and revolutionized criticism. But it backfired spectacularly when Kael tackled American cinema’s 800 pound gorilla: Citizen Kane.

Part II.

Bantam Books wanted to publish Kane’s screenplay, and in 1968 asked Kael to pen an introduction. To many observers, this seemed an obvious combination. Kane had long since cemented its reputation as Hollywood’s greatest movie; who better to review it than America’s premier critic?

Kael seemed ideal, not only for her prestige but her admiration for Welles. In 1967 she wrote an essay praising Welles as one of America’s great filmmakers, “the one great creative force in American film in our time.” In her essay collection Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, Kael listed Kane as “the most controversial one-man show in history.”

This matched Kane’s popular perception. Its rapturous critical reception in 1941 was undercut by William Randolph Hearst’s smear campaign, lukewarm box office and a near-Oscar shutout (of nine nominations, it only won for Best Screenplay). Over the next decade, Kane nearly vanished from America’s public consciousness.

Time vindicated Welles. France’s Cahiers du Cinema, belatedly discovering Kane after World War II, proclaimed Welles a genius; American critics, rediscovering it, agreed. His innovative style – Kane’s deep-focus photography, editing and exhaustive matte and miniature work – influenced innumerable movies. And Welles, catapulted from theater and radio to filmmaking at age 25, became an idol to filmmakers everywhere. “All of us will always owe him everything,” Jean-Luc Godard said.

But Welles never matched Kane’s success. Studio editors butchered his follow-ups, The Magnificent Ambersons and The Lady from Shanghai, which flopped. Welles spent much of his life in Europe. His subsequent films, from Othello to Chimes at Midnight, were haphazard affairs, impeccably directed but cash-poor, forcing Welles to start-and-stop production while pigeonholing investors for money. “I have lost years and years of my life fighting for the right to do things my own way, and mostly fighting in vain,” he lamented.

Casual moviegoers knew Welles better as an actor: The Third Man’s mischievous Harry Lime, Moby-Dick’s portentous Father Mapple, A Man for All Seasons’ rotund Cardinal Wolsey. He appeared in less prestigious projects too, from end-of-the-world documentaries to wine commercials. Welles considered these last degrading, but they provided him funds to sustain his projects and lifestyle.

Perhaps the effusive Welles worship soured Kael, overcoming her previous admiration. Granting a director sole credit for Citizen Kane was antithetical to the author of “Circles and Squares.” Instead, in Brian Kellow’s words, her essay became a “call to arms to defend Hollywood’s perennial underdog: the screenwriter.”

Part III.

Herman J. Mankiewicz was better known for his drinking and wit than his erratic screenwriting output. He was friends with William Randolph Hearst and his mistress, Marion Davies, spending long hours at their San Simeon estate (prototype for Kane’s Xanadu). Mankiewicz contributed to numerous films but rarely finished a whole script. “People who complain that my work is slipshod would be a little surprised to find that I just am not always satisfied with the first thing I put down,” he wrote.

Kane originated at a dinner at New York’s “21” Club, shortly after Welles’ Heart of Darkness fell through. Who broached the story? Certainly Mankiewicz’s relationship with Hearst gives him a strong case. But Welles also had Hearst connections: his father knew the tycoon as a young man, and his thematic preoccupation with men corrupted by power runs deeper than Mankiewicz’s comedy background. Regardless, their meeting proved fruitful: Mankiewicz accompanied John Houseman, Welles’ Mercury Theater co-producer, to Victorville, California to shape a screenplay.

By April 1940, Mankiewicz produced a 250 page draft entitled American. It prefigures the finished film in structure and protagonist, along with its Rosebud mystery. American provides a roman a clef of Hearst, incorporating incidents Mankiewicz witnessed firsthand (like Susan Alexander’s jigsaw puzzles, or Jed Leland failing to complete his review of a tycoon’s girlfriend). But American also depicts stolen elections, presidential assassinations and murders of romantic rivals, plucked from muckraking biographies and scandal sheets alike. Mankiewicz’s Kane becomes a tabloid caricature capable of any atrocity, undeserving of sympathy.

By Welles’ account, he and Mankiewicz worked on parallel scripts. While Welles played little role in Kane‘s early drafts, he mixed his own work with Mankiewicz’s story, then made further alterations during filming. Thus when Rita Alexander, Mankiewicz’s secretary, told Kael that Welles didn’t contribute to Mankiewicz’s script, she wasn’t wrong. But Welles’ secretary, Katharine Trosper, could say the same about Mankiewicz.

Ultimately, American went through seven drafts before becoming Citizen Kane. Welles removed Mankiewicz’s tawdrier episodes while developing his protagonist: “I found out more about the character as it went along.” Like Mankiewicz, he incorporated autobiographical elements: indeed, Kane’s background resembles Welles’ own more than Hearst’s. But Welles’ Kane emerged a tragic hero, a titanic, soured idealist destroyed by his incapacity for love.

Mankiewicz’s involvement waned as filming began; he rarely visited the set and grew distant from Welles. Mankiewicz disliked Welles’ changes, complaining that Kane became “too much like a play.” More seriously, Welles considered denying Mankiewicz credit through an authorship waiver in his Mercury contract. Fearing recourse from the Screen Writer’s Guild, Welles relented; he also agreed to credit Mankiewicz over him. But the damage was done.

Infuriated, Mankiewicz called Welles a “juvenile delinquent credit stealer.” As revenge, Mankiewicz started claiming he wrote Kane‘s script unaided. He felt some vindication when Kane‘s screenplay won the film’s only Oscar. Despite his initial chicanery, Welles spoke generously of Mankiewciz in later years; in a 1965 interview with Cahiers, Welles credited him with the film’s most powerful passages, including Mr. Bernstein’s lament about the persistence of memory: “I’ll bet a month hasn’t gone by since that I haven’t thought of that girl.”

“One marvels at the debt those two self-destroyers owe to each other,” wrote Mankiewicz’s biographer, Richard Merryman. “Without Welles there would have been no supreme moment for Herman. Without Mankiewicz there would have been no perfect idea at the perfect time for Welles.”

Mankiewicz died in 1953, another screenwriter lost to Hollywood history. His claims to Kane’s sole authorship passed on to his widow Sarah, children Tom and Frank, and John Houseman, embittered against Welles after a protracted falling-out. The dispute would have remained a footnote if not for Pauline Kael – and Howard Suber.

Part IV.

Suber, an assistant professor at UCLA, spent the late ’60s researching Kane and hosting a graduate seminar on the film. His research brought him in contact with several Kane veterans: editor Robert Wise, actress Dorothy Comingore (who played Kane’s wife, Susan Alexander) and Mankiewicz’s widow Sara among them. He also unearthed Kane‘s various screenplays. Suber’s research convinced him “the authorship of Kane [is] a very open question.” He explored the question in an essay written for another publisher’s edition of Kane‘s screenplay.

Meanwhile, Kael’s writing began in 1969. She spent over a year researching her story’s background: 1930s Hollywood, the lives of Welles and Mankiewicz, information on Hearst. She also contacted John Houseman, who enthusiastically recounted his version of Kane‘s development. “I am glad that Mank’s essential role in the making of that great film is finally to be recognized,” Houseman wrote. Kael also spoke with George Schaefer, Kane‘s producer, and Rita Alexander. Screenwriter Nunnally Johnson shared a damning anecdote with Kael, claiming that Welles offered Mankiewicz a $10,000 bribe for sole screenwriting credit.

Kael met Suber through a mutual friend and suggested they combine projects. Kael paid $375 for his research and the two worked together for several months. (Out of these discussions originated the canard that no one heard Kane’s last words, even though Raymond the butler clearly admits it.) As 1970 drew on, however, Kael became more and more distant, until contact ceased entirely. While Suber’s wife was suspicious, Suber didn’t think much of it: “Why would the biggest film critic in America need to screw some little assistant professor at UCLA?”

While many Kane actors and crew members remained alive in 1970, Kael contacted only three, none of whom played a direct role in the film’s development. Her most obvious omission was Kane himself, Orson Welles, who was famously accommodating to interviewers. Asked why she avoided Welles, Kael commented: “I already know what happened. I don’t need to talk to him.” She later admitted to Joseph McBride that she planned to write “a brief for Mankiewicz.”

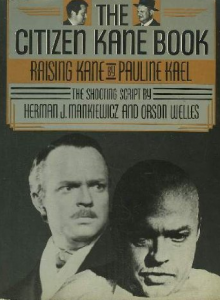

Kael convinced her New Yorker editor, William Shawn, to run her essay prior to the screenplay’s publication. On February 20th and 27th, 1971, after two-and-a-half years of development, “Raising Kane” appeared in two New Yorker installments. It generated such acclaim that Bantam contracted with Little, Brown for a special hardcover project, featuring the script, Kael’s essay and the film’s continuity notes. In October 1971, this appeared as The Citizen Kane Book.

The ensuing debate barely included Howard Suber, who read Kael’s essay with indignation. She used his research without accreditation or acknowledgment. Among other indignities, Dorothy Comingore angrily called Suber about Kael using her quotes in the article. He later compared the experience to “[being] raped by my parish priest.”

Part V.

At 47,052 words, “Raising Kane” impresses in size, if not content. To lay readers, it’s a typically muscular and provocative Kael essay. Cineastes must wonder if Kael lost her mind.

In Kael’s hands, Kane hardly seems a classic at all. She calls it “a shallow masterpiece,” “kitsch redeemed,” “a comic strip of Hearst.” She tries to qualify these statements, noting Welles’ use of melodramatic devices from theater and radio, but the tone seems condescending. As does her comparison of the “entertaining” Kane with supposedly non-entertaining great films like The Rules of the Game and Man of Aran. A strange introduction tor the film’s published screenplay!

strip of Hearst.” She tries to qualify these statements, noting Welles’ use of melodramatic devices from theater and radio, but the tone seems condescending. As does her comparison of the “entertaining” Kane with supposedly non-entertaining great films like The Rules of the Game and Man of Aran. A strange introduction tor the film’s published screenplay!

Kael blends this analysis with slanted portraits of Kane‘s creators. Kael dwells on gossip about ’30s Hollywood: Mankiewicz’s career and screenwriting friends, his stays at San Simeon, specious anecdotes and quotes from his boosters. Aside from his drinking, Mankiewicz seems a swell guy betrayed by the System. He becomes a beacon for writers everywhere who had their credit stolen by others – a bold statement from Kael, given her treatment of Howard Suber.

Meanwhile, Welles is too busy promoting himself to direct Kane. He’s an ignorant putz blundering into a masterpiece, whose greatest achievement was keeping his shortcomings secret. She writes that “he needed the family to hold him together on a project and to take over for him when his energies became scattered. With them, he was a prodigy of accomplishments; without them, he flew apart, became disorderly.” Hardly the genius she’d praised four years earlier.

“Raising Kane” has other problems, namely Kael’s bizarre contextual musings. She’s on firm ground comparing Kane to William K. Howard’s The Power and the Glory (1933), scripted by Preston Sturges. Welles claimed not to have seen that film, but its flashback-driven depiction of a tycoon’s rise and fall seems a reasonable match (in structure, if not style). If Welles didn’t see it, perhaps Mankiewicz did. Similarly, her comments about Kane‘s visuals invoking German Expressionism ring true, though she overlooks Welles’ experimentation with chiaroscuro in his Mercury Theater days.

But Kael stumbles comparing Kane to ’30s screwball comedies, repeatedly invoking Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur’s The Front Page. Beyond featuring newspapers, what resemblance does that zany satire share with Welles’ brooding character study? Nor does Kael’s comparison of Susan’s disastrous singing debut to the Marx Brothers’ Night at the Opera hold water, even if Mankiewicz co-produced that film.

Kael credits Gregg Toland, Kane‘s cinematographer, with the film’s mise-en-scene. Welles never claimed otherwise; he lauded Toland in interviews and even shared his title card with him. Kael ignores this, along with Welles’ admiration for Toland’s work on John Ford’s The Long Voyage Home. Instead she obsesses over Kane‘s alleged similarities to Karl Freund’s horror movie Mad Love, based on Peter Lorre’s baldness and pet cockatoo. This connect-the-dots movie-matching resembles the auteurist games she previously ridiculed.

“Raising Kane” can’t be commended as film history or critical analysis. But a long, passionately-argued piece by a famous writer carries its own weight. In responding, Welles’ admirers had their work cut for them.

Part VI.

Initially, “Raising Kane” received ecstatic reviews. Readers inundated The New Yorker with letters; The Citizen Kane Book became a best-seller and went through several printings. Reviewers enjoyed it too: In The New York Times, Mordechai Richler called it “a highly intelligent and entertaining study.” Film Quarterly called “Raising Kane” “How the history of American film ought to be written.”

Those close to Mankiewicz appreciated Kael’s support. Nunnally Johnson called it “a first-rate account and I’m a better man for having read it.” Tom Mankiewicz recalled “We all just said, ‘Herman did everything, and thank you so much, Pauline Kael’.” John Houseman was more cautious: “In her excitement over vindicating Mankiewicz… she ended up underestimating Orson’s contribution to the tone and quality of Citizen Kane.”

Backlash began with Kael’s nemesis, Andrew Sarris. On April 15th, Sarris responded in The Village Voice. His short column accused Kael of superficiality, repeating scurrilous gossip and condescension towards Welles. “It is only by virtually ignoring what Citizen Kane became… that Miss Kael can construct her bizarre theory of film history,” Sarris claimed.

Joseph McBride offered more substantial criticism. Then preparing a book on Welles (published in 1972 as Orson Welles), McBride had befriended Welles, who cast him in his film The Other Side of the Wind. McBride couldn’t help noticing Kael’s veiled but obvious swipe at him. When she mentions “articles on Citizen Kane that call it a tragedy in fugal form and articles that explain that the hero of Citizen Kane is time,” she’s paraphrasing a piece McBride wrote in 1968. Ironically, McBride discussed Mankiewicz’s contributions at length in his book Persistence of Vision: A Collection of Film Criticism.

McBride published an article in fall 1971’s Film Heritage entitled “Rough Sledding With Pauline Kael.” Like Sarris, McBride swipes at the shallowness of Kael’s analysis but also at her rigged argument. “What value is criticism which consists merely of opinions without reference to facts?” He quotes Peter Bogdanovich, then preparing his own critique of Kael, and concluded that “It’s an infuriating shame that to resurrect [Mankiewicz’s] name Miss Kael had to try to bury Orson Welles in the process.”

The following spring Jonathan Rosenbaum, another Welles scholar, contributed an essay to Film Forum called “I Missed it at the Movies.” Unlike Sarris and McBride, he says “Raising Kane is a work that has much to redeem it,” praising Kael’s style and research but not its content. “Even her highest tributes come across as backhanded compliments or exercises in condescension,” Rosenbaum writes, noting her misinterpretation of key scenes (for instance, missing the News on the March scene’s deliberate stylization) and constant putdowns. He also accuses Kael of pandering to her readers by slamming silent cinema, without specifying what films Kane invokes.

Welles’ collaborators and peers joined the backlash. Actor George Coulouris (who played Thatcher, Kane’s guardian) and composer Bernard Herrmann attacked Kael in Sight and Sound’s fall 1972 edition. Filmmakers William Friedkin and Ken Russell aided in Welles’ defense. “All directors change scripts: Welles always changed everything, Shakespeare included,” Russell noted in Films and Filming, while comparing Kael to ’40s gossip columnist Hedda Hopper.

Part VII.

Naturally, Orson Welles wasn’t pleased by “Raising Kane.” Already chafing from Charles Higham’s book The Films of Orson Welles, which framed him as a lazy egomaniac, he considered suing Kael for libel. “Wasn’t she saying… that I didn’t create Citizen Kane?” he raged to his attorney, Arnold Weissberger. But Weissberger convinced Welles there weren’t sufficient legal grounds. Welles also received royalties from The Citizen Kane Book, even though its introduction all but denied him credit.

In November 1971, Welles wrote an open letter to the London Times. He attacked Kael’s article, granting himself and Mankiewicz equal share in Kane‘s gestation. Welles wasn’t satisfied with this brief riposte, nor the legion of cineastes defending him. He tapped Peter Bogdanovich, the young filmmaker and critic who’d been interviewing him since 1969, to write a detailed rebuttal. By most accounts, Welles played a major editorial hand in the resulting essay.

Appearing in Esquire‘s October 1972 issue, a year-and-a-half after “Raising Kane’s” debut, “The Kane Mutiny” is part polemic, part legal brief. Bogdanovich claims that “It would require at least as many words [as Kael] to correct, disprove and properly refute it.” In much less space, he rebuts Kael almost point-by-point.

Bogdanovich interlaces “Mutiny” with copious interviews, including Welles himself. Howard Suber relates Kael’s theft of his research and criticizes her one-sided conclusion. Welles’ secretary, Katharine Trosper, rebuts Rita Alexander’s comments that Welles didn’t contribute to Kane‘s script: “Then I’d like to know, what was all that stuff I was always typing for Mr. Welles?” Charles Lederer, Mankiewiciz’s brother-in-law, disputes Kael’s claim that he gave Marion Davies a copy of Kane’s script.

Bogdanovich’s most damning witness is Richard Baer, an associate producer who swore under oath (during a 1941 arbitration) that Welles originated Kane‘s story and repeats his comments for Bogdanovich. Bogdanovich concludes that Kael knows little about Hollywood, noting from firsthand experience that scripts always change during filming. He adds that the Screen Wfriter’s Guild wouldn’t have awarded Welles credit if they weren’t satisfied with his participation.

Bogdanovich demolishes Kael’s analyses. He dismisses the Mad Love connection as “a wild parrot chase” and notices that Kane‘s visual style has its precursor not only in Toland’s work, but Welles’ own Mercury Theater productions. Like previous writers, Bogdanovich attacks her characterization of Kane as shallow and kitsch. He also attacks her for uncritically accepting anti-Welles testimony from Alexander, Houseman and Johnson while parsing Welles’ every word.

Reading “The Kane Mutiny,” Kael was stunned by Bogdanovich’s vehemence and thoroughness. She showed the essay to Woody Allen, asking him “How am I going to respond to this?”

“Don’t respond,” he suggested.

Kael followed Allen’s advice. But the debate didn’t end.

Part VIII.

The Kane fiasco scarcely dented Kael’s career. She remained at The New Yorker for twenty years, becoming its sole critic in 1979. She suffered a bigger hit in 1980 when Renata Adler published “The Perils of Pauline” in The New York Review of Books, slamming Kael as a vulgar charlatan. The attack deeply wounded Kael, but she declined to respond. Her style influenced a generation of critics; even filmmakers like Wes Anderson and Quentin Tarantino admired her. She died in September 2001.

Welles continued pursuing unfinished projects, including Don Quixote and The Other Side of the Wind. Meanwhile, he continued lending his talents to films he despised. “I play a planet. I menace somebody called Something-or-other. Then I’m destroyed,” he said about his penultimate role – Unicron in Transformers: The Movie. Welles’ death in 1985 erased these unpleasant memories; he’s remembered for his triumphs rather than late-career kitsch.

Kael’s thesis was definitively debunked by Robert L. Carringer, whose essay “The Scripts of Citizen Kane” painstakingly documents Kane’s drafting process, granting both Welles and Mankiewicz a share in its creation. Yet her argument lives on. For one, Simon Callow’s The Road to Xanadu claims Welles “slashed through Mankiewicz’s text…. He added none of his own words.” And Herman Mankiewicz’s descendants continue positing him as Kane’s sole author. “It was not written at all by Orson Welles,” Frank Mankiewicz told the Washington Post in 2013.

It’s no insult to Welles’ collaborators to say he was Citizen Kane‘s primary mover. Mankiewicz’s role in shaping Kane can’t be denied, any more than Gregg Toland’s photography, Bernard Herrmann’s music or Welles’ costars. But Herrmann’s own assessment seems definitive: “Citizen Kane was arrived at through an inner compulsion on the part of Orson Welles.”

At her best, Pauline Kael was an insightful, acerbic critic unafraid to air controversial opinions. At her worst, she was a discursive, bullying contrarian unable to argue consistently. “Raising Kane” exhibits the latter tendency: for all the juicy anecdotes and brisk prose, her analysis is shallow and her content dubious. Evidently, Kael considered the essay a chance to destroy the hated auteur theory. Unfortunately, in this case few facts were on her side.

Selected Sources and Acknowledgements:

Selected Sources and Acknowledgements:

Books: Frank Brady, Citizen Welles (1989); Robert L. Carringer, The Making of Citizen Kane, Revised Edition (1996); Pauline Kael, The Citizen Kane Book (1971); Brian Kellow, Pauline Kael: A Life in the Dark (2011); Joseph McBride, What Ever Happened to Orson Welles? A Portrait of an Independent Career (2006)

Articles: Peter Bogdanovich, “The Kane Mutiny” (Esquire, October 1972); Robert L. Carringer, “The Scripts of Citizen Kane” (Critical Inquiry, Winter 1978); Pauline Kael, “Circles and Squares” (Film Quarterly, April 1963) and “Raising Kane” (The New Yorker, February 20 and 27, 1971); Joseph McBride, “Rough Sledding With Pauline Kael” (Film Heritage, Fall 1971); Ken Russell, Films and Filming (May 1972); Jonathan Rosenbaum, “I Missed it at the Movies: Objections to Raising Kane” (Film Comment, Spring 1972); Andrew Sarris, “Films in Focus,” The Village Voice (April 15, 1971).

This article owes a serious debt to Wellesnet, the excellent Orson Welles web resource. Several of the articles listed above are available through their site. Special thanks to Ray Kelly for providing research suggestions and guidance.

Joseph McBride shared his insights on Kane, and generously provided his article “Rough Sledding With Pauline Kael” for my perusal.

Thanks to Reuvain Borchardt and Dave Jenkins for helping me locate “The Kane Mutiny.”