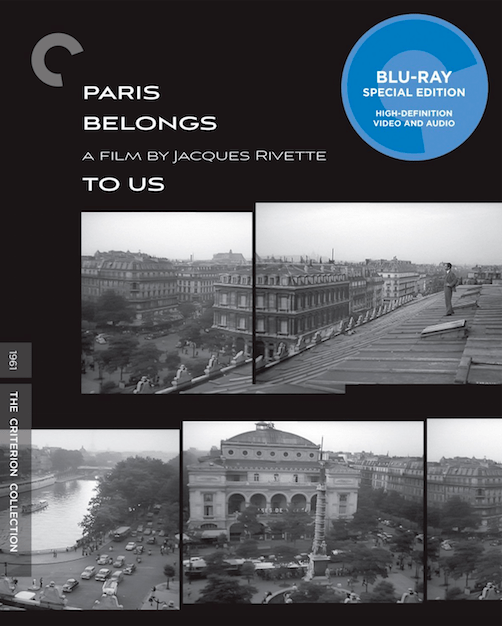

Paris Belongs to Us

Paris Belongs to Us

Written by Jacques Rivette, Jean Gruault

Directed by Jacques Rivette

France, 1961

The first and most obvious point of contention or contradiction concerning Jacques Rivette’s Paris Belongs to Us is the Charles Péguy quote that opens the film: “Paris belong to no one.” While this declaration seems to fly in the face of what the film’s title states, the question doesn’t stop with why Rivette instantly counters the name of his own movie; it becomes, which is, in fact, the case? Is the Paris of this film an inclusive locale, one that belongs to everyone or even just a select group of people, or is it an inaccessible world hostile to ownership, a city that strives on its own independent wavelength? Rivette’s debut feature therefore “starts with a puzzle,” as author Richard Neupert puts it, before the story proper even gets underway. And it doesn’t stop there. Over its 141 runtime, Paris Belongs to Us is riddled with paradoxes, inconsistencies, deceit, and ambiguity.

Neupert and others commenting on Paris Belongs to Us also call attention to the film’s opening credit sequence, which appears to take the position of a point of view shot from someone looking out a window as a train enters Paris. It’s never clear who is looking, so there is some debate about whether or not this vantage point is that of the film’s main character, Anne (Betty Schneider, previously seen in Jacques Tati’s wonderful Mon Oncle from 1958). Are we supposed to be following along with the girl’s arrival in Paris? If so, how much time has passed from this initial entrance to where the film picks up, when Anne is established in the city? That there is even dispute about this opening—which I would argue is simply a situating cityscape backdrop under the credits (it’s showing Paris for a film set in Paris)—is indicative of a film that raises more questions than answers and provokes endless interpretation, even when it may not be so necessary.

Neupert and others commenting on Paris Belongs to Us also call attention to the film’s opening credit sequence, which appears to take the position of a point of view shot from someone looking out a window as a train enters Paris. It’s never clear who is looking, so there is some debate about whether or not this vantage point is that of the film’s main character, Anne (Betty Schneider, previously seen in Jacques Tati’s wonderful Mon Oncle from 1958). Are we supposed to be following along with the girl’s arrival in Paris? If so, how much time has passed from this initial entrance to where the film picks up, when Anne is established in the city? That there is even dispute about this opening—which I would argue is simply a situating cityscape backdrop under the credits (it’s showing Paris for a film set in Paris)—is indicative of a film that raises more questions than answers and provokes endless interpretation, even when it may not be so necessary.

In any case, as the film begins we are with Anne, a young student who meets up with her brother, Pierre (François Maistre, later to star in a number of Luis Buñuel’s finest films), and through him she begins an association with a tight-knit group of individuals, most of whom coalesce around a theatrical troupe led by director Gérard Lenz (Giani Esposito). At a party, discussion turns to the death of Juan, a friend and musician who was working on the now lost score for the group’s staging of Shakespeare’s controversial Pericles. Juan’s death, however, an apparent suicide (though that remains uncertain), is the cause of much speculation and bitterly conflicting opinion. There appears to be some mystery surrounding the circumstances of his passing, most of which has to do with a pervasive sense of paranoia and the suggestion that nefarious forces were behind Juan’s demise.

Throughout the film, Anne is our only real point of emotional engagement or identification, and though she initiates the investigation into what really happened to Juan and where his recording is, she is ultimately left as bewildered as we are. She falls for Gerard and is promptly warned against him. Is he also in danger, or is he a cause of the danger? What about the others? To make matters worse, death seems to be spreading and nobody is safe. Anne’s neighbor vanishes at one point and raises some alarm at first, but her condition is soon of little consequence. Similarly, bizarre drawings in the room of Philip Kaufman (Daniel Crohem), a writer seeking refuge from Communist witch hunts in America, resemble cartoonish creatures with angry, evil faces, yet such incongruously childish images are never questioned. Little details in the film are made apparent, register as potentially noteworthy, then frequently slip away never to merit mention again. And all roads keep coming back to Juan and his missing “music of the apocalypse.”

Throughout the film, Anne is our only real point of emotional engagement or identification, and though she initiates the investigation into what really happened to Juan and where his recording is, she is ultimately left as bewildered as we are. She falls for Gerard and is promptly warned against him. Is he also in danger, or is he a cause of the danger? What about the others? To make matters worse, death seems to be spreading and nobody is safe. Anne’s neighbor vanishes at one point and raises some alarm at first, but her condition is soon of little consequence. Similarly, bizarre drawings in the room of Philip Kaufman (Daniel Crohem), a writer seeking refuge from Communist witch hunts in America, resemble cartoonish creatures with angry, evil faces, yet such incongruously childish images are never questioned. Little details in the film are made apparent, register as potentially noteworthy, then frequently slip away never to merit mention again. And all roads keep coming back to Juan and his missing “music of the apocalypse.”

The severity of the film’s foreboding apocalyptic tone is repeatedly alluded to in such doomsday prophesying phrases as “Am I going mad? Or is the world?”, “The world isn’t what it seems,” and “We must prepare. The hour approaches.” Kaufman is especially prone to ambiguous commentary: “I speak in riddles,” he says, “but some things can only be told in riddles,” or simply, “Juan knew terrible things.” Indeed, Juan is known to have talked of corruption and the end of the world, notions that point toward a supposed grand global conspiracy. Paris Belongs to Us is set in June of 1957 (it was actually shot in 1958 but took nearly three years to see a release), and as such, it is representative of the times, speaking to fervent attitudes of nihilism, anarchy, rebellion, and revolution.

Threatening premonitions and unsettling suggestions of worldwide domination at the hands of various organizations all lead to an incessant paranoia, a paranoia that could, however, be built on delusion. Under constant fear of imposing power, these characters appear often on the run, but we are never sure just who they think is pursuing them. When authorities apparently show up in an apartment building, for instance, we only hear a little from behind a closed door, never actually seeing the inferred figures. Everyone in this circle is open and extroverted, but things are always left unsaid. This is a tense clique, a group close to one another but always looking out on the sly for any hint of backstabbing or ulterior motivation. The Paris that belongs to these individuals is inclusive, in that Anne is quickly welcomed to the fold and once ingrained seldom departs from their company. Yet their Paris is also limited, in that it functions autonomously from the apparent mainstream of society and seems to operate on a distinct plane of existence.

Threatening premonitions and unsettling suggestions of worldwide domination at the hands of various organizations all lead to an incessant paranoia, a paranoia that could, however, be built on delusion. Under constant fear of imposing power, these characters appear often on the run, but we are never sure just who they think is pursuing them. When authorities apparently show up in an apartment building, for instance, we only hear a little from behind a closed door, never actually seeing the inferred figures. Everyone in this circle is open and extroverted, but things are always left unsaid. This is a tense clique, a group close to one another but always looking out on the sly for any hint of backstabbing or ulterior motivation. The Paris that belongs to these individuals is inclusive, in that Anne is quickly welcomed to the fold and once ingrained seldom departs from their company. Yet their Paris is also limited, in that it functions autonomously from the apparent mainstream of society and seems to operate on a distinct plane of existence.

This is also a strange looking Paris, with obscure streets, an absence of the neon lights that typically illuminate the city, and architecture shown to be commonplace, decrepit, or simply just there. This Paris has no bustle, no life. The constrictive interiors are otherworldly in their seclusion, further dislocating everyone from the outside. Rivette and cinematographer Charles L. Bitsch shot mostly in natural light, with exceptionally dark nights expressing the doom of a noir. The exterior day-time scenes, on the other hand, have the feeling of a stagnant late afternoon entering a moment of anxious pause before night falls. Like the Italy of Michelangelo Antonioni’s La notte (1961) and L’eclisse (1962), this is an unkind and unwelcoming French setting. Even the Arc de Triomphe looks menacingly down on Anne as she roams the desolate streets. Still, the picture is beautifully photographed, with a slightly off kilter interplay of angles and staging in depth. And adding amplification to the discord is Philippe Arthuys’ score, a composition of disassociated noises ranging from animalistic murmurs, to vocal harmonizing, to steely sounds that all somehow merge into an atmospheric mélange of musical miscellanea.

Despite the time and place of its production and release, it is difficult to place Paris Belongs to Us as an emblematic work of the French New Wave. It may feature a turn by familiar face Jean-Claude Brialy and it resembles those features from François Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard in the sense that it was shot on location with borrowed equipment, little money, and an unconventional script. But there is no humor in Rivette’s film, no youthfulness, no light formal playfulness, even if there is experimentation. There are a few allusions to politics and cinema itself (look for cameos by Godard, Claude Chabrol and Jacques Demy), but Paris Belongs to Us, as much as film with that title should, does little to romanticize the city in the way The 400 Blows (1959) or Breathless (1960) does.

Written by Jean Gruault, who would go one to pen additional scripts for Rivette as well as Godard and Truffaut, Paris Belong to Us is formed of scattered pieces, abounding chaos, and irrational situations. In discussing Pericles, the argument is made that the work, like the world, can end in some logical cohesion. One can’t say the same for this film. As Neupert states, in this “labyrinthine” feature, Rivette is constantly questioning perceived intentions and manipulating perspective (the characters’ and the viewers’). Paris Belongs to Us defies genre and defies even the loose standards of the New Wave. It does, however, undeniably represent the cinema of Jacques Rivette. It is an auspicious beginning for a filmmaker who would tread similar territory for the rest of his illustrious career.