Dressed to Kill

Dressed to Kill

Written and directed by Brian De Palma

USA, 1980

Whether one loves or hates his work, Dressed to Kill is a quintessential Brian De Palma film. It is a tour de force of his trademark flourish, with long takes, flowing camera movements, and a superbly stylized sense of composition, particularly his integration of split-screens and split-diopter shots (nobody does either quite as well). It also encompasses a number of his most frequent thematic fixations, namely voyeurism, deceptive perception, and the commingling of a consuming obsession with an equally charged aggression. Now, that is all for those who like his movies. For those who do not, there is the contentious misogyny, the abundant allusions to Hitchcock (detractors would say blatant rip-offs), and the lingeringly gratuitous sex and violence. As a dedicated De Palma devotee, I am much more likely to side with those in the former camp, but I can see in Dressed to Kill some of the better arguments concerning the latter. Still, even with this possible—though admittedly flimsy—concession, I hold this 1980 film up as a classic. It is the first of three fantastic features in a row (with Blow Out [1981] and Scarface [1983] next in line) for a director who remains one of the most underrated in American cinema.

A repressed, unsatisfied sexuality gets Dressed to Kill on its way, as Kate Miller (Angie Dickinson) departs her house following a hurried and unfulfilling early morning romp with her husband. After a visit with her psychiatrist, Doctor Robert Elliott (Michael Caine), to whom she voices her troubles, she stops off at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (only on the outside; interiors were shot at the Philadelphia Museum of Art), where she finds herself enamored by a stranger, a stranger who seems to be enticing her along. Sure enough, they wind up back at his room for an anonymous rendezvous. Later that evening, she dresses and heads back home, shaken to her core when she discovers the stranger has been diagnosed with a venereal disease. Before she can make it out of the apartment building—spoiler alert—she is slashed to death with a straight razor, her blonde-haired, female assailant unclear save for a few distinguishing features, notably dark sunglasses and a dark trench coat; key accessories and articles of clothing (however minimally they clothe) are a prominent motif throughout Dressed to Kill and more than once they play a crucial role in the narrative. As crafted by De Palma, this murder is an expertly arranged orchestration of camera angles, make-up effects, multiple points of view, and shockingly bloody violence, and Kate’s brutal, seemingly random death rouses the suspicion of her son, Peter (Keith Gordon), who with prostitute Liz Blake (Nancy Allen), a witness to the gruesome scene, begins an investigation into the attack.

A repressed, unsatisfied sexuality gets Dressed to Kill on its way, as Kate Miller (Angie Dickinson) departs her house following a hurried and unfulfilling early morning romp with her husband. After a visit with her psychiatrist, Doctor Robert Elliott (Michael Caine), to whom she voices her troubles, she stops off at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (only on the outside; interiors were shot at the Philadelphia Museum of Art), where she finds herself enamored by a stranger, a stranger who seems to be enticing her along. Sure enough, they wind up back at his room for an anonymous rendezvous. Later that evening, she dresses and heads back home, shaken to her core when she discovers the stranger has been diagnosed with a venereal disease. Before she can make it out of the apartment building—spoiler alert—she is slashed to death with a straight razor, her blonde-haired, female assailant unclear save for a few distinguishing features, notably dark sunglasses and a dark trench coat; key accessories and articles of clothing (however minimally they clothe) are a prominent motif throughout Dressed to Kill and more than once they play a crucial role in the narrative. As crafted by De Palma, this murder is an expertly arranged orchestration of camera angles, make-up effects, multiple points of view, and shockingly bloody violence, and Kate’s brutal, seemingly random death rouses the suspicion of her son, Peter (Keith Gordon), who with prostitute Liz Blake (Nancy Allen), a witness to the gruesome scene, begins an investigation into the attack.

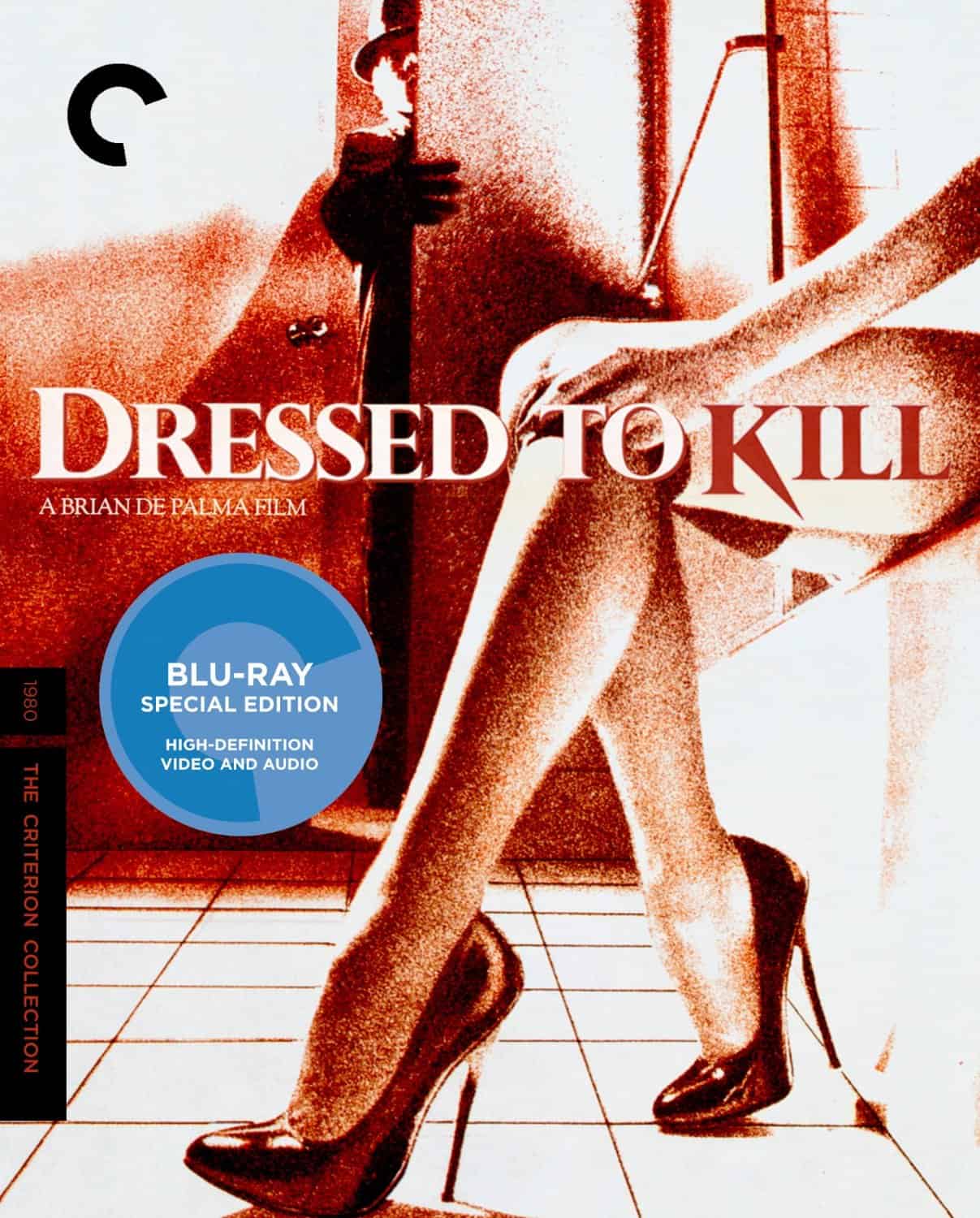

In one of several interviews included on the new Criterion Collection Blu-ray of the film, De Palma speaks of the genesis for Dressed to Kill and discusses how it, like much of his work, was born from “visual ideas.” Like those other titles, this is indeed a very visual film, with an oftentimes airy, luminous luster and some truly extraordinary sequences of prolonged tension (it is amazing how long De Palma will let a suspense scene play out), all of which is heightened by his balance of movement and montage. But he is also quick to likewise argue for the necessity of a good story and relatable characters, another area where Dressed to Kill excels. Though Kate is essentially only the subject of the film for about 30 minutes or so (and with her gone also goes what seemed to be the primary plot of the film), her character’s initial importance never wanes, not only because of Peter’s familial motivation, but because she was such a pronounced individual (Dickinson, in fact, considers the role the best work she has ever done). The same sort of immediate and lasting impression is felt with the entire primary cast and their respective characters. From the likable Allen and Gordon as an efficient, if improbable, duo, to Caine, always a first-rate actor, who whether we know it or not embodies the most complex character in the film, to even the bit players, like Dennis Franz as the tough-talking, wise-ass Detective Marino, by the film’s conclusion, we have invested a good deal in these few individuals, and in a relatively short period of time.

In one of several interviews included on the new Criterion Collection Blu-ray of the film, De Palma speaks of the genesis for Dressed to Kill and discusses how it, like much of his work, was born from “visual ideas.” Like those other titles, this is indeed a very visual film, with an oftentimes airy, luminous luster and some truly extraordinary sequences of prolonged tension (it is amazing how long De Palma will let a suspense scene play out), all of which is heightened by his balance of movement and montage. But he is also quick to likewise argue for the necessity of a good story and relatable characters, another area where Dressed to Kill excels. Though Kate is essentially only the subject of the film for about 30 minutes or so (and with her gone also goes what seemed to be the primary plot of the film), her character’s initial importance never wanes, not only because of Peter’s familial motivation, but because she was such a pronounced individual (Dickinson, in fact, considers the role the best work she has ever done). The same sort of immediate and lasting impression is felt with the entire primary cast and their respective characters. From the likable Allen and Gordon as an efficient, if improbable, duo, to Caine, always a first-rate actor, who whether we know it or not embodies the most complex character in the film, to even the bit players, like Dennis Franz as the tough-talking, wise-ass Detective Marino, by the film’s conclusion, we have invested a good deal in these few individuals, and in a relatively short period of time.

De Palma also stresses the importance of sound design for his films, comparing the right sound to hear at any given moment with the most effective color on a canvas. This type of careful selection is clear when most diagetic sounds drop out during the famous museum courtship, one of several wordless sequences where only very specific points of aural focus are cued up, or when Peter uses his techno-sleuthing skills to eavesdrop on the conversation between Marino and Elliott, where De Palma isolates the dialogue and similarly obscures the background noise.

Nevertheless, that Dressed to Kill is a visual film first and foremost is evidenced by some distinctly De Palma formal strategies. The careful placement of mirrors, windows, and other screens within screens give the film a dense layering of multiple planes, which coincides with the recurrent shots of people watching others by way of these various features, and which is further significant thematically, as we then become the ones watching someone watching someone. It is all about looking with De Palma: us at them, them at each other, both with a voyeuristic secrecy. This particular facet of the director’s work was by 1980 par for the course.

Nevertheless, that Dressed to Kill is a visual film first and foremost is evidenced by some distinctly De Palma formal strategies. The careful placement of mirrors, windows, and other screens within screens give the film a dense layering of multiple planes, which coincides with the recurrent shots of people watching others by way of these various features, and which is further significant thematically, as we then become the ones watching someone watching someone. It is all about looking with De Palma: us at them, them at each other, both with a voyeuristic secrecy. This particular facet of the director’s work was by 1980 par for the course.

Working in aesthetic harmony, the audiovisual union of Dressed to Kill is thus exceptional. As Michael Koresky notes in his excellent essay on the picture, “De Palma’s film, thanks in part to Ralf Bode’s sensuous, soft-lens camera work and Pino Donaggio’s ecstatic, romantic score, is a work of baroque, intensely cinematic horror.” The sense of luxurious romanticism that therefore results lulls one into a sedate yet engrossing atmosphere, only to be spoiled abruptly and effectively by the sudden violence. It is a genuine cinematic seduction every bit as potent as the fictional ones taking place on screen.

Dressed to Kill’s reception is mentioned in several of the interviews included on the Criterion disc, but there are also separate features examining in detail the different versions of the film and how it was re-cut in order to obtain an R rating. Even still, the final version managed to ruffle more than a few feathers (albeit nothing quite like what De Palma encountered four years later with Body Double). “This film is a minefield of potential offense,” writes Koresky, “with its horrific butchery of a middle-aged woman and its full-frontal images of naked women shot like soft-core pornography…. it was bound to incite some anger.” In De Palma’s twisted spin on transexuality, he likens the identity confusion and subsequent materialization of latent desires and volatile behavior to something akin to a Jekyll and Hyde transition (with connotations that probably would not sit lightly these days). And in a making-of documentary, a number of preproduction changes are also mentioned, like the removal of Kate’s voiceover narration. More prominent, however, was De Palma’s decision not to shoot his original opening of a transsexual (presumably Elliott) performing a self-penectomy. One can only imagine how that would have gone over.

Dressed to Kill’s reception is mentioned in several of the interviews included on the Criterion disc, but there are also separate features examining in detail the different versions of the film and how it was re-cut in order to obtain an R rating. Even still, the final version managed to ruffle more than a few feathers (albeit nothing quite like what De Palma encountered four years later with Body Double). “This film is a minefield of potential offense,” writes Koresky, “with its horrific butchery of a middle-aged woman and its full-frontal images of naked women shot like soft-core pornography…. it was bound to incite some anger.” In De Palma’s twisted spin on transexuality, he likens the identity confusion and subsequent materialization of latent desires and volatile behavior to something akin to a Jekyll and Hyde transition (with connotations that probably would not sit lightly these days). And in a making-of documentary, a number of preproduction changes are also mentioned, like the removal of Kate’s voiceover narration. More prominent, however, was De Palma’s decision not to shoot his original opening of a transsexual (presumably Elliott) performing a self-penectomy. One can only imagine how that would have gone over.

All controversy aside, Dressed to Kill has a perfect blend of De Palma story with De Palma style, where each is equally in the service of the other. Unlike some of his films, where the technique trumps the plot (Snake Eyes [1998], Passion [2012]), or where the narrative, either convoluted or ridiculous, burdens the form (Wise Guys [1986], The Bonfire of the Vanities [1990]), Dressed to Kill gets the balance perfect, and as such showcases why those who are fond of De Palma frequently count the film among his best.

All controversy aside, Dressed to Kill has a perfect blend of De Palma story with De Palma style, where each is equally in the service of the other. Unlike some of his films, where the technique trumps the plot (Snake Eyes [1998], Passion [2012]), or where the narrative, either convoluted or ridiculous, burdens the form (Wise Guys [1986], The Bonfire of the Vanities [1990]), Dressed to Kill gets the balance perfect, and as such showcases why those who are fond of De Palma frequently count the film among his best.

Jeremy Carr