This is Part 1 of a 4 part series leading up to the release of The Hunger Games: Mockingjay – Part II, each looking at an individual film in the series and it’s legacy.

The Hunger Games series is special. It does things differently, operates on a different spectrum than most blockbusters. Some of the ways in which this is true are obvious. It works as definitive proof that females can front enormous blockbusters. It’s also a series that at least somewhat legitimizes the Young Adult genre, giving it a little more heft than Twilight and its other predecessors. The most important ways in which this series is unique are more subtle, though. The Hunger Games movies are about something. To be more specific, they’re about violence, media manipulation, and what war really means for those who wage it.

The Hunger Games itself, the first film in the saga, is interested in all of these things. It’s a film that was eagerly anticipated before its release, and wildly successful afterwards. It was a blockbuster in every sense of the word, and it became the third highest grossing film of 2012. This was the year of The Avengers, one where that film completely dominated the box office. These films are interested in fundamentally different things. The Avengers is a symptom of its moment, a film with a climax full of destruction and action. The Hunger Games is also a symptom of this moment, but it works in opposition to it.

The Hunger Games asks its audience to imagine a world where violence and entertainment are the same thing, one where children are shipped off to kill each other in order to keep those in power where they are. It’s impossible to hear a premise like this and not think of the ways we entertain ourselves. We watch news stories about violent crime because those stories get better ratings. We watch movies where superheroes destroy entire cities because those movies sell more tickets. And we watch movies like The Hunger Games because we get to see the incredible violence these children display.

This violence is a trap though. It’s not meant to be enjoyed. The entire premise of The Hunger Games is meant to critique the casual way in which we kill onscreen. When you hear the film described, though, it sounds like a movie that will allow its viewers to find pleasure in this violence. The Hunger Games had to work very hard to avoid allowing its audience to become the Capitol.

Fortunately, the film makes several moves to avoid this pitfall. Gary Ross, who directed this first installment, makes the violence feel both immediate and completely non-gratuitous. The use of shaky-cam, often described as the film’s greatest fault, allows the film to depict this violence without reveling in it. If anything, the instability of the camera jostles the audience to such an extent that the film becomes difficult to watch. He overcompensates, working too hard to make the violence real. A shaking camera is not something you see in most blockbusters. Blockbuster cinematography is steady, and it allows to audience to take in every second of the action onscreen. Framing the action this way may keep the audience entertained, but it detracts from the immediacy of the violence. Ross’s direction makes you feel the moments onscreen, even if it makes the moments themselves less entertaining.

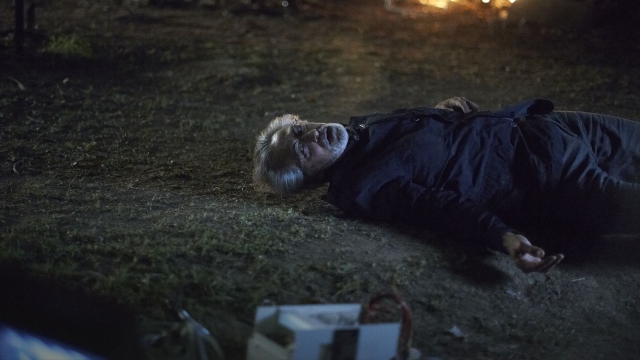

The style of the camerawork is complimented by the writing. The screenplay, also written by Ross, never shows anything other than disgust toward the games and what they represent. Rue’s death is perhaps the most potent example of this. The death of a child is horrific enough, but Rue’s plays out in such a sudden splash of horror and violence that it is impossible to enjoy it. Instead, we are left with Katniss, who is completely destroyed by the loss of this young girl. As Katniss sings Rue to her death, we take on Rue’s point-of-view. We see the beauty of the world through her eyes, as the tops of the trees in the arena fade to white. This imagery, haunting as it is, is impossible to revel in. Her death is a moment that makes us feel. It’s one that stands out, because it recognizes Rue’s death as pointless, as a moment that didn’t have to occur. It’s a palpable experience, one that is emblematic of the movie as a whole. The Hunger Games is interested in what these deaths do, and ensuring that they affect us.

Rue’s death stings so enormously because it is a terrifying, horrible reminder that she is a person. She’s a small child trapped in unbearably awful circumstances. These reminders of humanity exist throughout the film. Cato provides another at the film’s close, one that turns the film’s primary antagonist into what he’s been all along: a pressured adolescent. He holds Peeta and screams at the world, “I’m dead anyway. I always was, right? I didn’t know that till now. How’s that? Is that what they want?” Cato is mad at a world which has forced him to become this malevolent figure. He’s become a puppet, something to be used and disposed of.

Peeta expresses exactly what Cato feels to Katniss before they even enter the arena. “I just don’t want to be another piece in their game, you know?” Peeta’s worries are about sustaining his own humanity. He is worried about becoming someone he is not in order to survive. This doesn’t mean that he won’t kill anyone. It simply means that he wants to be more than someone else’s entertainment, more than a tool to keep the masses in line. He wants to prove that, even in horrible circumstances, he has remained who he was before the games began.

The Hunger Games fights to remind us of its characters’ humanity. Cato’s final moments make him someone sympathetic, someone who was put into this horrible situation for the same reasons as everyone else. He’s the ostensible villain of the film, but his last words reveal a humanity that he had merely hidden in order to survive. Peeta wears this humanity on his sleeve. He’s concerned with losing who he is from the very beginning, and his conversation with Katniss comes to reinforce the film’s belief that these tributes are more than mere objects for viewing pleasure. Blockbusters are no longer interested in moving their characters beyond the realms of pleasure. They want us to ignore the implications, and focus on only the actions and plot of the film. The Hunger Games is unique because it’s interested in psychology, in how these teenagers feel in the horrible world they are thrust into. It’s interested in the ways in which they are people.

This is something we seem to have forgotten. The citizens of the Capitol don’t understand that the tributes they throw into the arena every year are anything more than objects. They see the games as something distant, a foreign piece of entertainment that breaks up their day-to-day lives but has no lasting impact. We do this too. We hear about a shooting, and instead of being marred in the tragedy, we move on with our day. Violence is so pervasive in our lives that it doesn’t make us feel anything.

The Hunger Games wants us to think about the violence we so rarely feel. This is rare for a blockbuster movie, a genre which could do so much if it was interested in saying something. They reach huge numbers of people all over the world. Instead, they play it safe. They are too worried about scaring people away to have any real impact. The Hunger Games lives in a world where killing someone, or watching them die, is a traumatic experience. The Hunger Games cares about the way its images affect viewers. It’s aware of its influence, and tries to wield it as a weapon.